This post is an excerpt from a speech I gave last week at the Oklahoma City Chamber of Commerce’s state of the schools event.

We’re in the midst of the biggest backlash to education reform in a decade, if not a generation. While some in the movement believe we need to just improve our message, or find new messengers, my sense is that our challenges run much deeper. If we’re going to succeed over the long haul, we need to take a hard look not just at how we’re selling, but also at what we’re selling. We need to look at our reform agenda and ask ourselves: Is it working? Do the pieces fit well together? Does it diagnose the problem correctly and offer the right cures?

This is where we’ve made our biggest mistakes: getting the diagnosis wrong. Specifically, we have diagnosed all of our schools as having the same disease, and prescribed the same medicine for all of them.

In many of our reform conversations, there’s been a lot of tough talk about “failing schools,” and the need to “blow up the system.” And heaven knows there are some terrible schools out there, and broken, dysfunctional systems.

But let me ask you: do you send your children to public schools? Do you think your own public schools are broken, failing, need to be blown up?

I’m a public school parent. I don’t think my son’s school is broken or failing. It’s not. And neither, probably, are your kids’ schools.

Those of us who live in affluent areas, mostly in the suburbs, moved to those communities in large part because of the good public schools. So when we hear all this talk about failure, and the need for radical change, it doesn’t resonate. If reforms threaten to harm our schools—by turning them into test-prep factories, or by messing with the way they teach math—it makes us angry. As well it should.

That’s not to say that all is well in the leafy suburbs. The problem in middle-class and upper-middle-class communities, in my opinion as a policy wonk and as a parent, is mediocrity. The schools are okay. They’re pleasant, welcoming, well-ordered, and optimistic. But, for the most part, they are not great. I don’t see a whole lot of evidence that most schools in the suburbs are asking themselves every day: How can we get better? How can we take our students (who tend to come in with the advantages of stable homes and involved, educated parents) and their learning to new heights? How can we make sure that every professional in our building is excellent, always improving, and giving 110 percent?

In our elementary schools in particular, I see a lot of complacency. My son has learned more about history and science from watching PBS Kids than from his school. That’s a problem.

My sense is that the affluent schools get more serious as the kids get older, as they get closer to college, as opportunities for Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate courses kick in. At least the highest achieving kids start to get challenged.

But truly challenging kids is a rarity in American education. That’s the takeaway from Amanda Ripley’s great book, The Smartest Kids in the World, which follows three American teenagers as they journey overseas as exchange students. And what they all realize is just how easy American school is compared to schools in other countries. And the exchange students who come here say the same thing: “Wow, American schools are a breeze.”

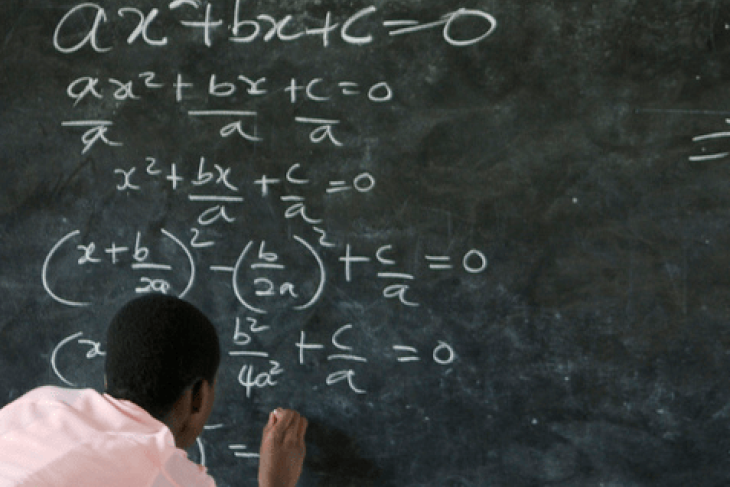

Should our schools be drudgery? Of course not. They need to be places of intellectual discovery, excitement, and enthusiasm. Why is it that we believe only in challenging our kids to do their very best when it comes to athletics, or music, or the arts—domains where the American school system excels? Kids want to be challenged; they want to be pushed to excellence. We do that in football. We could do it with fractions, too.

I believe that reforms like the Common Core can help schools in the suburbs immensely. High standards—and rigorous, aligned tests—can tell children and their families the truth about whether students are “on track” for college or a meaningful career. They also indicate the essential knowledge and skills that kids need to master at each grade in order to be on the trajectory for success. And good suburban districts tend to have the capacity—the central office staff, the know-how, the resources—to rise to the challenge of higher standards.

What’s not a good fit for these middle class schools are policies that take power away from local school boards and local educators, such as a mandatory state curriculum or a formulaic system to evaluate teachers using a template created by a far-away state bureaucrat, and one that encourages teaching to the test. These sorts of reforms are overkill in the suburbs, and they understandably frustrate local parents, teachers, and administrators.

***

A separate issue is what to do about our high-poverty schools, the ones serving mostly low-income children, many of them coming from single-parent homes, and tough neighborhoods, with caregivers who are working two or three jobs, and don’t speak English.

From my experience, and from my examination of the data, most of even these schools are not “failing.” (To be sure, some are—the dropout factories, the dangerous schools, the brain-dead institutions that have been oblivious to wave after wave of reform.) But on the whole, high poverty schools tend to be no better and no worse than the average school in the affluent suburbs. Their teachers work just as hard, the curriculum and methods they use are much the same. Like most of our schools they are OK. Mediocre.

But here’s the difference: For kids growing up in poverty, mediocrity is not enough. OK is not enough. Pretty good is not enough. Because those children—our children—are starting school so far behind, and because their disadvantages are so enormous, we need their schools to be excellent, fantastic, awesome, audacious, if these children are going to scale the mountain to college or a good paying career, to climb the ladder to the middle class, to live the American dream.

The kids growing up in affluent families—kids like mine and yours—can survive “pretty good” schools. If we are doing our job at home we don’t need their schools to be dynamite. Our kids are going to be OK, they are going to go to college and get good jobs. We’ll make sure of it.

But most poor children don’t enjoy these same advantages. Most are growing up without fathers, most have moms who are stretched thin by low-wage work, many aren’t hearing English spoken in the home, most come into school—even pre-school—several years behind. Their schools need to be excellent if they are going to be put on a path to success.

I understand that’s a lot to ask of an education system. It would be better if we didn’t have so many single-parent families, or so much poverty. But I’ve yet to see serious solutions to those problems that don’t rely heavily on education as the route to the middle class for this generation of kids.

So the challenge for the high-poverty schools is immense. The most excellent urban schools in the country tend to be high performing No-Excuses charter schools that have the freedom and drive to obsess about excellence every day, to ensure that every adult in the building is top-notch and giving his or her all, to uphold high standards for student behavior and effort, and to create a culture of success. I’m doubtful that big bureaucratic districts can replicate that kind of school, and for that reason I think most big cities are going, ten or twenty years from now, to have systems dominated by charter schools, instead of school systems as we know them today. And if we can get the policies right and the accountability piece right, our kids will be better off for it.

Our challenge as reformers is to diagnose our problems correctly, and prescribe the right medicine. And that means, first and foremost, stopping the one-size-fits-all policies, the top-down mandates that apply to all schools, in all situations. It’s like a hospital sending all of its patients to the cancer ward, even the ones with cardiovascular disease. We need to get smarter. We need to differentiate. We need to stop painting with such a broad brush.

We tell educators they should “differentiate” their instruction for the needs of their students. It’s time we take our own medicine and “differentiate” our reforms for the needs of our schools.