Should Ohio move to computer adaptive testing?

State tests are an important annual check-in for parents, teachers, communities, and policymakers, as they provide an objective assessment of student achievement based on grade-level standards.

State tests are an important annual check-in for parents, teachers, communities, and policymakers, as they provide an objective assessment of student achievement based on grade-level standards.

State tests are an important annual check-in for parents, teachers, communities, and policymakers, as they provide an objective assessment of student achievement based on grade-level standards. Accompanying growth measures offer a different, though no less important, snapshot of student progress from year to year. Because state tests are standardized, they make it possible to track achievement and growth over time, and to compare student populations and schools. Such comparisons are often the best way to pinpoint problems (say, for instance, learning loss courtesy of a global pandemic), evaluate the effectiveness of specific policies (like third-grade reading retention), and ensure that all students—regardless of race, gender, disability, or geographic location—have access to quality schools and educational opportunities.

In short, the information that tests provide is crucial. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t room for improvement. In fact, there are plenty of ideas out there about how to make tests more engaging, how to gather better information, and how to make sure the process remains rigorous and fair. Not all of these ideas are a good fit for Ohio. But there is one that Ohio leaders should consider: computer adaptive testing.

As the name suggests, computer adaptive tests adapt to students during the assessment process via computer software. When taking traditional, “fixed form” tests—what Ohio currently uses for its state exams—the difficulty level is the same for all students. With adaptive tests, however, the difficulty of students’ questions is determined by their previous responses. Although all students are tested on their current grade level standards, students who answer questions correctly are provided harder items and those who struggle are provided easier ones. (To better understand how questions are selected for each student, check out this video from the Virginia Department of Education.) The goal is to provide students with questions that are neither too difficult nor too easy. By targeting questions to a student’s ability level, the assessment provides a much clearer picture of what students know.

Computer adaptive tests have several benefits. For students, taking a test that finds a happy medium between questions that are too challenging and too easy is a much more engaging process than traditional testing. Students who are advanced are less likely to get bored, those who struggle are less likely to get frustrated, and all students benefit from a more personalized opportunity to show what they know. Furthermore, because customizing questions can determine mastery quickly, the test could end up being shorter for some students. That’s not possible with fixed form assessments, which provide a specific number of questions that must be answered regardless of whether a student has already demonstrated mastery.

Many Ohio students are also already familiar with adaptive assessments thanks to the tests their schools administer for diagnostic purposes. NWEA, for example, has been approved as an alternative testing vendor by the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce. Over 40 percent of Ohio students take MAP growth, NWEA’s computer adaptive assessment that measures student performance in math, reading, and science. i-Ready, another vendor that’s been approved by the state and is widely used in Ohio schools, offers adaptive tests. Ohio’s Alternate Assessment for Students with the Most Significant Cognitive Disabilities—a federally required state assessment—is computer adaptive. The SAT is now fully digital and adaptive. And the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) is computer adaptive, too.

For educators and parents, adaptive tests promise more actionable results. By providing a more precise assessment of where students excel and where they struggle, these tests can help teachers and parents personalize support and intervention to address specific topics rather than general, grade-level areas.

For policymakers, advocates, and researchers, adaptive tests could lead to better, more exact measures of student growth on state report cards. This has the potential to allow for a more precise gauge of whether students learned a year’s worth of material in a year’s time, something current state assessments don’t do. If so, we’d have a clearer picture of which schools are doing excellent work and which ones might need more support. Transitioning to adaptive testing should also be relatively easy. ESSA, the federal education law, permits states to administer statewide assessments in the form of computer adaptive tests. And although Ohio would likely be required to update its ESSA plan to make the switch, state officials wouldn’t need to worry about federal approval. Many states already administer computer adaptive tests as their annual exams, including Virginia, Michigan, and Indiana.

Given all these benefits, it seems like a no-brainer for Ohio leaders to consider transitioning to computer adaptive testing. But the key word here is “consider.” Even the smallest change to state tests can cause controversy and strife if handled incorrectly, and this wouldn’t be a small change. Furthermore, although many students and teachers might be familiar with adaptive testing, many parents might not be. Failing to communicate clearly and preemptively address misconceptions could be a death knell. Timing is also an issue. With so many other policy challenges on their plates, state lawmakers need to proceed with caution.

To ensure that computer adaptive tests don’t become yet another promising idea that’s doomed by hasty adoption or lackluster implementation, state policymakers should call for a feasibility study. As part of this study, officials at the Department of Education and Workforce could examine the work of other states, evaluate different ways to bring adaptive testing to Ohio, gather feedback from key stakeholders, and recommend ideas that could head off potential problems. The results of this study would give leaders plenty of Ohio-specific feedback to incorporate into eventual policy and practice. Most importantly, starting with a feasibility study would ensure that Ohio has all its ducks in a row before making such a big change. Computer adaptive testing could be great for the Buckeye State—but only if we do it right.

With a 3-2 vote last week, the Upper Arlington school board signed onto a lawsuit that aims to strike down Ohio’s EdChoice scholarship program. First enacted in 2005, EdChoice today provides financial assistance to roughly 130,000 students to defray, or fully cover, the cost of private school attendance. Historically, scholarship eligibility has generally been limited to lower-income families, but legislators in recent years have allowed more parents to access the program. Legislation passed just last year made all Ohio families eligible for scholarships, with wealthier families eligible for partial scholarships.

The expansion of EdChoice has riled up the public-school establishment, which perceives the program as a threat to its longstanding hegemony over K–12 education. To protect their interests, choice opponents have (in addition to litigation) embarked on a PR campaign aimed at bashing private schools. The “Vouchers Hurt Ohio” group, which receives support from more than 100 school districts, accuses private schools of “siphoning” money from public schools, a claim that flies in the face of empirical evidence showing EdChoice has no impact on districts’ per-pupil expenditures. The group also attacks the program for creating a “system of state-funded discrimination,” even though private schools must follow non-discrimination policies and have served countless low-income, Black, and Hispanic students through the years.

If all this melodramatic rhetoric weren’t enough, now we get this: One of the state’s wealthiest school districts is trying to strip educational choices from less advantaged families by joining the lawsuit.

Serving a posh enclave just outside of Columbus, Upper Arlington had the fourth highest median resident income and the forty-ninth highest property valuation per pupil of Ohio’s 608 school districts in 2022–23. Its average teacher salary ($91,306) ranked fifth highest statewide and the district spent $17,677 per pupil, 15 percent above the statewide average. This spending figure excludes capital outlay, so it wouldn’t even reflect the district’s recently completed, $235 million school facilities upgrade.

I’ve got no quarrel with residents in affluent communities using their own resources to generously support public schools. Decades ago, I benefitted from attending a well-off school district that provided a good education. What’s unfathomable is when districts like Upper Arlington use their power and prestige to harm families who are less fortunate.

Let us recall that this year alone, some 27,500 Black and Hispanic students received an EdChoice scholarship. If EdChoice goes away, children from poor families and distressed neighborhoods in cities like Columbus will be forced to trek back to an “assigned” public school that may be unsafe or provide a substandard education. Without EdChoice, working-class families from all across the state will need to make much tougher decisions about whether they can afford a private school for their sons and daughters.

Most of the district leaders and residents of Upper Arlington are fortunate not to have to make those types of agonizing decisions for their children. Their well-resourced public schools work for the vast majority of students, and the state’s scholarship program—even an expanded one—has a next-to-nil impact on the district. Why advocate to snatch educational opportunities from the hands of disadvantaged Ohio families? Why heap scorn on the private schools that serve some of the state’s neediest students—something that wealthy districts like Upper Arlington refuse to do by forbidding open enrollment?

Perhaps the Upper Arlington school board didn’t fully understand the ramifications of their actions. Maybe they got caught up in the political theater. Whatever the case may be, the result was a shameful, sickening display of elite power and privilege.

Teacher pipelines and shortages have been a hot topic in Ohio the last several years. One of the biggest talking points has been that fewer students seem interested in the profession. A 2019 report from the Center for American Progress found that enrollment in teacher preparation programs fell nationally from 2010 to 2018, and that Ohio posted a decline of nearly 50 percent. State data released last year reflected the impact of these drops, with the number of newly licensed teachers having gradually declined since 2014.

Federal data released this spring, however, indicate that Ohio might have reason for hope. Title II of the Higher Education Act focuses on post-secondary programs that recruit, train, and develop teachers. It includes oversight for teacher preparation programs via state- and institution-level report cards. The 2023 State Reports released this spring include data from the 2021–22 academic year (AY), as that’s what was reported to the U.S. Department of Education by its deadline in October 2023. The interactive site containing this data is worth a look. The tools provided allow for a deep dive into any state, as well as the ability to compare states and yearly data changes.

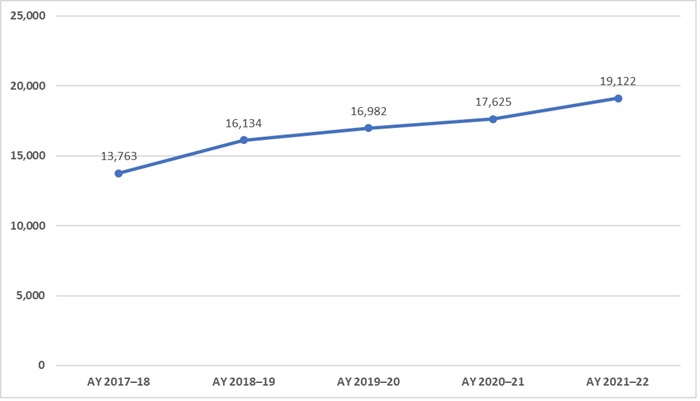

For Ohio leaders, there are two findings worthy of note. First, Ohio is one of more than a dozen states to see an increase in enrollment at teacher preparation programs. In fact, as Figure 1 shows, the number of individuals enrolling in traditional teacher preparation programs has steadily increased over the five most recent years of data available. During the 2017–18 academic year, just shy of 14,000 prospective teachers enrolled in traditional preparation programs. By 2021–22, that number had climbed above 19,000.

Figure 1: Trend in Ohio’s traditional teacher preparation program enrollment

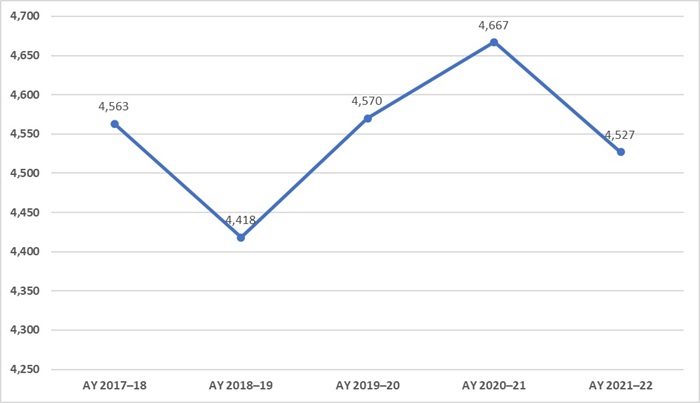

Second, although the number of teacher candidates enrolling in preparation programs is climbing, the number of program completers has been mostly flat. Figure 2 shows that the number of completers in 2021–22 is roughly the same as in 2017–18, with increases or decreases of roughly one hundred completers in the intervening years. That’s not too worrisome; it typically takes four years to complete a teacher preparation program, so the significant jump in enrollment during the 2020–21 and 2021–22 school years wouldn’t yet be reflected in completion numbers. But if next year’s data don’t reveal a noticeable bump in the number of completers to match the gradually increasing enrollment numbers, then policymakers and advocates will need to ask some tough questions of preparation programs.

Figure 2: Trend in number of program completers

There are some important caveats to consider along with these findings. As previously mentioned, the federal data highlighted above are from the 2021–22 academic year. Given the lag that’s typical with federal data collection efforts, we don’t have up-to-the-minute numbers through this source. It is possible that, over the course of the last two years, Ohio has experienced even more growth in enrollment in teacher preparation programs, or perhaps there’s been another worrisome dip. Either way, the recent enrollment bumps are good news, as they should translate to more teachers.

Ohio is also in desperate need of more and better data on its teacher workforce. Although federal data are helpful, they might not tell the whole story. There could be state or local data or context that paint a different picture. But if such data do exist, they’re not easily or readily available to policymakers or advocates. In a similar vein, unless the state starts to annually collect and publish data about teacher demand and vacancies, it will remain difficult to understand the true breadth and depth of teacher shortages. Without this information, policy solutions won’t be as timely and effective as they could be. Ohio lawmakers should consider addressing these issues in the upcoming budget.

Even with these caveats, though, there’s reason for hope. The federal numbers look promising for Ohio. And over the last few years, state lawmakers have taken some important steps to bolster the teacher pipeline. These include provisions to make teacher licensure more flexible, to expand the pool of substitute teachers, to establish a Grow Your Own Teacher Scholarship Program, and to create a Teacher Apprenticeship Program. There’s still more work to be done and plenty of ideas that should be enacted. But based on this available information, Ohioans have reason to feel a little less doom and gloom about teacher shortages going forward.

This is fourth in a series in which I examine issues in K–12 education that Ohio leaders should tackle in the next biennial state budget. Previous pieces covered the science of reading as well as funding for low-income pupils and interdistrict open enrollment. This essay looks at guarantees.

One of the most vexing problems in school finance is reliance upon provisions that shelter districts from funding reductions. At first blush, these provisions—known as “guarantees”—don’t sound so bad, and cutting funding is never politically appealing, no matter the circumstance. But school districts do change and sometimes do so in ways that should reduce their need for state aid. Districts that are losing enrollment have fewer expenses and thus require less funding. Meanwhile, those with increasing local wealth they can tap into should have less need for state assistance, too.

A well-functioning state funding formula would adjust district allocations for those types of changes. But guarantees circumvent the formula, providing excess funds above and beyond formula prescriptions to ensure a district’s funding doesn’t fall below some historical level. This is problematic on both fairness and efficiency grounds. In terms of fairness, guarantees amount to special handouts given only to certain districts, a “pork barrel”–type method of allocating dollars that can end up shortchanging districts more in need of state aid. They also treat parents and students unfairly, as they weaken districts’ incentives to serve them well in an effort to keep them as “customers.” If no funding is lost when parents and students head for the exits, schools have fewer incentives to improve. As for efficiency—a school funding concept enshrined in the Ohio Constitution—guarantees promote fiscal largesse, as districts can avoid trimming budgets to account for smaller enrollments. They also represent a poor use of taxpayer dollars, as they send funds to educate what are in effect “phantom students.”

Despite these problems and some attempts to root them out, Ohio has long embedded guarantees into its funding system. The Kasich administration used to prod the legislature to address guarantees, as have we at Fordham. More recently, the Cupp-Patterson school funding plan seemed to promise their demise, too. In their advocacy push a few years ago, plan proponents attacked Ohio’s old funding system as a “patchwork” whereby hundreds of districts were funded via guarantees while others were “capped.” Instead, they pledged a model that “bases state school funding on actual student need … and treats all Ohio school districts and taxpayers fairly, based on capacity to pay.” In other words, supporters claimed that this plan would finally move the state toward a system in which the formula is scrupulously followed. An early projection from advocates suggested that the plan would immediately cut the number of districts on the guarantee from roughly half to just one-sixth, and one school group official predicted that, over time, “a need for a guarantee should go away.”

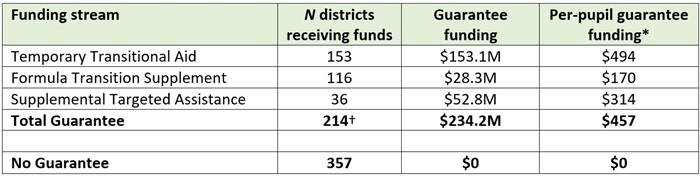

The Cupp-Patterson model—now billed the “Fair School Funding Plan”—was enacted in 2021, and the third year of implementation (fiscal year 2024) is drawing to a close. Yet Ohio’s funding system still includes guarantees that protect hundreds of districts from funding reductions otherwise prescribed by the formula. While some progress has been made in removing districts from the guarantee, 35 percent remained on one as of FY24. That’s not fast enough progress, especially given the pledges made by the Cupp-Patterson advocates. Three funding streams in particular comprise the guarantee given to certain districts this year:[1]

Taken together, these items cost the state approximately a quarter-billion dollars this year, or $457 per pupil. While not a huge sum in the context of the state’s entire education budget, this is more than the state is spending on the Science of Reading initiative ($169 million over two years) and above its annual expenditure on career-technical-education categorical funding (roughly $215 million this year).

Table 1: Guarantee funding for Ohio districts, FY2024

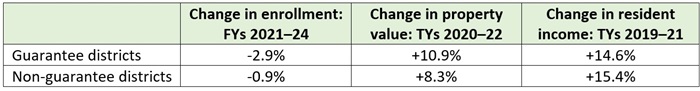

As shown in Table 1, not all districts benefit from the guarantee. And as noted earlier, guarantees tend to subsidize districts that are losing enrollment and/or growing in local wealth, factors that should reduce their need for state assistance. Table 2 shows that the districts on the guarantee have indeed experienced larger enrollment declines in recent years: -2.9 percent versus -0.9 percent for non-guarantee districts from FY21 to FY24. Their property values have also increased at a faster clip than non-guarantee districts, though resident incomes have not.

Table 2: Characteristics of districts on a guarantee

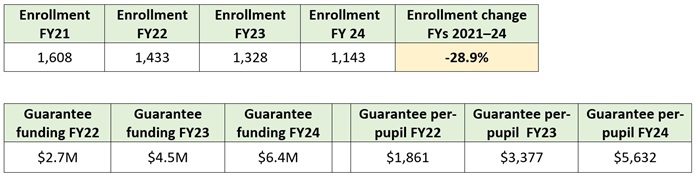

That guarantees can be a crutch for shrinking districts is starkly illustrated by looking at East Cleveland City School District, far and away the biggest beneficiary of the guarantee on a per-pupil basis. In FY24, the district received a staggering $5,632 per pupil in guarantees, an amount that sends the district’s overall state funding to levels that are way out of line with similarly situated districts. For instance, East Cleveland this year received roughly $24,000 per pupil in total state aid, whereas nearby Cleveland Metropolitan School District received a more rational $9,700 per pupil from the state.[2] East Cleveland’s massive guarantee, which it has received in all three years of Cupp-Patterson implementation, shields it from the state funding reductions that would otherwise occur due to its rapidly declining enrollment (-28.9 percent from FY21 to 24).

Table 3: East Cleveland school district enrollment trends and guarantee funding

School funding guarantees are bad public policy. They undermine the principles of a fair and efficient funding system designed to deliver dollars to districts via formula. They misdirect funds to districts that are less in need of state assistance and enable shrinking districts to avoid making necessary budgetary decisions that promote good stewardship of taxpayer funds. In the next budget bill, state legislators should fulfill what the Cupp-Patterson plan initially promised Ohio: a state funding system that treats schools, students, and taxpayers fairly. Removing guarantees from the system—and actually following the formula—would be a big step toward instituting a school funding model that is “fair” in more than name only.

[1] This doesn’t include other guarantee-like mechanisms in the formula, such as the staffing minimums inside the base-cost formula that benefit small districts, or a minimum state share percentage for high-wealth districts.

[2] CMSD was mostly funded via strict formula but received $160 per pupil in supplemental targeted assistance.

Kudos to the Strada Education Foundation for its brand new State Opportunity Index, designed to gauge how well post-secondary education in each state prepares graduates to join the workforce and earn a living wage. The index establishes a baseline for how states are doing in five priority areas: clear outcomes, quality coaching, affordability, work-based learning, and employer alignment.

The resource begins with a state-by-state return on investment (ROI) calculation for graduates who earn bachelor’s and associate degrees. To determine the ROI, the index compares the cost of obtaining a degree—including paying off student loans within ten years of completion—to the individual earnings that a graduate can expect based on the type of degree they earn.

At the top of the heap, 78 percent of degree-earners in California and New York can expect a positive ROI within ten years of completion. The lowest is Idaho, at 54 percent. Bachelor’s degree holders can generally expect a quicker positive return than their peers with associate degrees, despite the substantially cheaper price tag of the latter. Only three states—New Mexico, Vermont, and Wyoming—show a stronger ROI for associate degree earners than for those who earn bachelor’s degrees. Workers who are making at least $50,000 per year are likely to experience positive ROI in even the most expensive state. Workers earning less than $30,000 per year, on the other hand, will not experience positive ROI no matter how inexpensive their postsecondary education was, as their earnings do not exceed those of a high school graduate with no degree.

The bulk of the index then looks at those five priority areas and provides a rating for each.

The “clear outcomes” priority examines whether the data are available to allow high school students to know what their post-secondary education journey will look like—trade school, university, certification, apprenticeship, military service, etc.—and what types of jobs each option could lead them to. The biggest winners here were states whose data sources connected education and employment across numerous agencies and were (or were becoming) publicly available.

The “quality coaching” priority asks whether college students received timely information and guidance to help them navigate their chosen pathway. Data come from a national survey of college graduates from 2020 to 2023. On the upside, students who reported receiving coaching saw measurable benefits from it. On the downside, all states individually and the nation as a whole ranked very low in providing employment-related coaching to post-secondary students.

The “affordability” priority looks to see how well states eliminate cost as a barrier to postsecondary education. These data were calculated based on the number of hours a college student would need to work annually—while earning their state’s median wage—to cover the net price of their education. California and Washington are the most affordable; Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Montana, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and South Dakota are the least. These outcomes, like the ROI analysis, are driven mainly by the median incomes in the various states.

“Work-based learning” describes the number of students who completed an internship (paid or unpaid) during college and the benefits of those internships. Data again come from that big national survey. Graduates who complete a paid internship are much more likely to end up with a first job that requires their degree (73 percent), compared to those who did not (44 percent). They are also more likely to be satisfied with their first job and their progress toward their long-term career goals, compared to students who completed an unpaid internship or no internship at all. Internships were more prevalent for bachelor’s degree students (approximately 50 percent) than for associate degree students (approximately 25 percent). Associate degree students were more likely to have unpaid internships, while their bachelor’s degree peers had paid internships.

Finally, the “employer alignment” area scores each state on the supply/demand ratio of workers for a variety of high-demand and high-wage jobs, including cybersecurity, health care technician, software development, and engineering. The methodology for this important area is restrictive, focusing only on jobs that require bachelor’s degrees (and fewer than three years of experience) and only on bachelor’s degree earners who have these jobs. Additionally, the analysts aren’t able to factor in graduates who move to another state in pursuit of a job after earning their degree or who live in one state but work remotely in another. Since this area is restricted only to talent supply and demand data within a single state, it is probably not surprising to see low grades for all of them.

For each priority, the index gives a raft of recommendations aimed at helping states climb the rankings. My colleague Jessica Poiner has taken a deep dive into Ohio’s ratings and what they mean. All states could benefit from taking these findings and recommendations seriously.

Yet the index itself has room for improvement: expanding its focus to include non-college pathways to opportunity (such as military service and credentialing), looking at how K–12 education impacts these priority areas, and an examination of how remote work figures into economic opportunity, to name just three.

SOURCE: Strada Education Foundation, “State Opportunity Index: Strengthening the Link Between Education and Opportunity” (May 2024).

Note: Today, the Ohio House’s Primary and Secondary Education Committee heard testimony on Senate Bill 168 which would, among other things, deregulate many aspects of K-12 education in the state. Fordham’s Vice President for Ohio Policy provided interested party testimony on the bill’s main provisions and several amendments intended to be added. These are his written remarks.

The intent behind SB 168—education deregulation—is one that Fordham wholeheartedly supports. We actually published a report on the topic all the way back in 2015. Unfortunately, like many well-intentioned efforts before it, SB 168 doesn’t go far enough in its efforts to deregulate and—where it is bolder—there’s been a push to remove those provisions from the bill. I’d encourage this committee in the coming years to find more areas where we can relax input measures to give educators more flexibility on how to help each child reach his or her potential. At the same time, it will be important to maintain outcome measures, high expectations, and transparency.

Given the nature of the legislation, SB 168 has many different issues that it touches. As such, I apologize in advance for not having a strong narrative connecting my comments on the bill’s various components. Instead, for the sake of efficiency, I’ll go through the key aspects of the bill where we have feedback individually.

First, I’ll focus on the provisions of SB 168 as passed by the Senate. Next, I’ll shift to commentary on those amendments that I’m aware are being considered by some committee members. That, of course, isn’t likely to be a comprehensive list.

3302.151—related to exemptions for high performing districts

3319.111—related to district developed teacher evaluation protocols that differ from OTES

3302.421—related to remote administration of required state assessments

3319.273 (new section)—related to administrator licenses

3319.172—related to making decisions on merit rather than seniority for nonteaching staff

Now, I’ll shift to amendments potentially under consideration.

Dyslexia training

Adjusting the graduation rate calculation for students with disabilities

Sponsor evaluations for the 2024-2025 school year

E-School enrollment limits

Automatic closure provisions for district and community schools

* * *

Thank you for the opportunity to provide testimony today on Senate Bill 168 and some of the potential amendments. Education deregulation is an important topic, and something that we believe—even after this bill is moved forward—is still very much a work in progress. I’m happy to answer any questions that you may have.