- With ECOT closed, a special master appointed by the court to help oversee things like records transfer and asset management, and families working to find new schools that are at least the second-best fit for their kids, it seems there is little else for education reporters to write about. Especially if they actually want to report on anything of substance. (Columbus Dispatch, 1/19/18)

- Per the above, I picture staff members at school districts across the state standing around the front entrance to their buildings today like frustrated guests at the world’s saddest surprise party – waiting and waiting and waiting to welcome guests who just aren’t going to arrive. But let’s not let reality get in the way of a good clip, shall we? We’re all better than that. In the vein, here is a story on what some districts in Stark County have planned to help their seniors graduate on time at the end of this school year. Very little of it sounds inspiring or indeed very helpful at all. The current “on track/likely to be on track” numbers for the various school districts are enlightening though. That surprise party in Canton might be the saddest of all. (Canton Repository, 1/21/18)

- Apropos of nothing at all, I’m sure, Galion City Schools is advertising an upcoming info session (in person, on site, at the district HQ of course) in order to “introduce or reintroduce” the district’s online learning opportunities to anyone interested in finding out. It will be held next week. So, that’s like holding the world’s saddest surprise party two weeks late and in a dentist’s office. (Richland Source, 1/20/18)

Earlier this week, Chiefs for Change (CFC) announced that Ohio’s Superintendent of Public Instruction, Paolo DeMaria, joined their network. CFC is a nonprofit, bipartisan network comprising state and district education chiefs who advocate for innovative education policies and practices, support each other through a community of practice, and nurture the next generation of leaders. The network is made up of members who lead education systems serving 7.2 million students, 435,000 teachers, and 14,000 schools.

According to the CFC website, members of the network “share a vision that all American children can lead fulfilling, self-determined lives as adults.” Though it is made up of diverse members with various viewpoints, the chiefs find common ground in five key areas: 1) access to excellent schools, 2) quality curriculum, 3) fully prepared and supported educators, 4) accountability, and 5) safe and welcoming schools.

Here’s a look at a few specific policies supported by CFC and what they look like in Ohio:

School choice

In a statement on school choice released last year, CFC members asserted that “school choice initiatives have the potential to dramatically expand opportunity for disadvantaged American children and their families.” We’ve seen this firsthand in Ohio, where school choice options like high-performing charter schools and open enrollment policies have led to improved student outcomes and a broader range of opportunities. To be sure, Ohio’s record isn’t spotless. There’s still plenty of work to be done. But the Buckeye State is on the right track, and we’re confident that Superintendent DeMaria will continue to focus on quality choices for all families in Ohio.

School funding

School funding has long been a hot topic in Ohio. As part of their support for quality educational opportunities for all students, CFC advocates for “fair funding for schools proportionate to the learning needs of students.” In layman’s terms, this means that taxpayer funding should go to the students who need it most. As former state budget director and associate superintendent of ODE’s school finance office, few in Ohio have a deeper knowledge of the state’s funding system than Superintendent DeMaria. Lending his voice to ensure that all students, no matter their choice of schools, have the resources necessary to succeed would be powerful as legislators wrestle with funding policies.

Teacher policy

CFC believes that teachers should be well-prepared, rewarded for their skills and impact on student learning, provided with opportunities to expand their leadership, and supported with timely and meaningful evaluation and feedback. To his credit, Superintendent DeMaria has already been active in this area: In the fall of 2016, he asked the Educator Standards Board to review the Ohio Teacher Evaluation System. This resulted in recommendations that have now been incorporated into Senate Bill 240, legislation introduced last December that could improve the evaluation system. DeMaria was also vocal about refining the Resident Educator Summative Assessment for educators new to the profession; that initiative yielded significant revisions.

Accountability

Last year, Ohio lawmakers began mulling possible changes to the state’s school report cards. Fordham offered a few recommendations to consider, including simplifying the report card and creating a better balance between achievement and growth metrics. At CFC, members have voiced their support for holding schools accountable for student learning according to “standards benchmarked against those of high-performing states and countries.” Their stance has also included support for “radical change” in struggling schools, which they argue is not only possible but reliably doable. Ohio has an accountability system that, though it could use some simplification and tweaks, is strong compared to other states. Our ESSA plan—recently approved by Secretary DeVos—already contains many of the policies and practices that CFC advocates for. As the debate continues over how to improve Ohio’s school report cards, having a state chief willing to maintain high academic expectations will be essential.

***

Of course, DeMaria doesn’t have to heed any of CFC’s recommended policies and practices. But by joining CFC, he has made clear his commitment to opening quality educational opportunities to all and finding ways to lift student outcomes. We commend him for taking this bold step forward.

- The 2018 Quality Counts ratings are out and very little has changed for Ohio from the previous year. Doesn’t stop folks from trying to spin those results into a vision of speculative doom. Our own Chad Aldis is quoted in this piece as the voice of anti-spin. (Columbus Dispatch, 1/17/18)

- On Wednesday morning, Chad was in the posh studios of WOSU-FM, taking part in an hour long radio talk show titled “The Future of ECOT”. Other guests included several ECOT alums and current parents. (All Sides with Ann Fisher, WOSU-FM, 1/17/18) So, how was “the future of ECOT” looking by the end of the day Thursday? Nonexistent. Chad is quoted in the PD piece on the vote which terminated the school’s operation as of today. (Cleveland Plain Dealer, 1/18/18)

- If a state’s ESSA plan is approved in a bureaucracy and no one is there to care, does it make a sound? Probably not, according to Patrick O’Donnell. (Cleveland Plain Dealer, 1/17/18)

- This piece is a bit out of the mainstream for Gadfly Bites (and I’m indebted to my colleague Jessica Poiner for drawing it to my attention), but stay with me as I explain. Oberlin College in northeast Ohio is profiled as a typical top-of-the-line, private, high-dollar liberal arts school with a big problem. It appears to be locked into an upward spiral of costs and tuition hikes while maxing out on the number of full-fee-pay students it is able to attract. Costs can’t be cut because of the high amount of fixed, input-related costs (think fancy dorms, expansive grounds, great food service, and lots of tenured faculty). Any cuts in these areas will have repercussions on the school’s reputation because its position as “one of the best in the country” is almost entirely due the value of those inputs, which officials fear will lead to even more difficulty in recruiting students. Whereas, judging by academic and employment outcomes for students puts this $70K-per-year institution somewhere around 300th place on a list of the same types of schools. So why is this relevant to my loyal Gadfly Bites subscribers? Because I have a feeling you could replace "private liberal arts college" with "independent private K-12 school" and have about the same article. The value is in the inputs and the brand. Just don't ask about the outcomes. But I could be wrong about that. (Christensen Institute blog, 1/17/18) Speaking of K-12 private school tuition, folks in Ohio are apparently just waking up to the knowledge that the recently-passed federal tax bill could allow them to use their 529 college savings plans to pay for some of the aforementioned private school tuition if they so choose. It is interesting to see who in the private school community is shouting, “This would be awesome!” and who in the private school community is hemming, “We’ll need to investigate the import of this further”. (Columbus Dispatch, 1/19/18) Sticking with the topic of private schools for one more clip, Cincinnati Waldorf School wants to move forward with its plans for a high school – what I think would be the first Waldorf high school in the entire state. They want to start next year with a single ninth grade class in a temporary location in the posh suburb of Mariemont, providing the city elders will allow it, with plans for additional grades and a permanent building in the future. Tuition at the K-8 school currently around $12K per year, so let’s hope that 529 plan works out. (Cincinnati Enquirer, 1/19/18)

- Finally today—and back in the real world with something of a bang—here is a partial list of the amazing features that Akron City Schools’ new website will offer once it goes live later this month: Teachers now can immediately upload news and information to a specific section of the site as it happens, quick links to special sections to view grades and receive messages from the superintendent (along with management of the placement of those links based on usage patterns), using color to help support navigation (i.e.-displaying each school's colors when users are in that school's section), automatic adjustment to whatever device the site is displayed on, a translation function on the homepage for several different languages, a newsletter function that allows user to subscribe to get news and information and receive get an email when new information is available, password-protected pages teachers can create for students and parents for special assignments, and a calendar function that integrates with Google, so each school can have its own calendar. Whew! I didn’t look to see what features are on the current version of the district’s website, but all I can say is “Welcome to the late 20th Century, Akron!” (Cleveland Plain Dealer, 1/18/18)

The fall conference season is well behind us, but a bad taste in my mouth lingers.

I’m struggling with the seismic shift in tone at these conferences, where education advocates traditionally assembled to give each other pep talks. In a few short years, we’ve gone from thinking we were right about everything—granted, that was kind of obnoxious—to adopting a rather pathetic and unattractive lament, professing just how wrong we’ve been about everything. I guess I prefer smug to self-flagellation.

Many advocates appear to be abandoning our once shared convictions about what it takes to lift children out of poverty, the very wellspring of the movement’s power and mass appeal. For years, we had stuck hard and fast to a sensible, winnable, and research-based strategy: improve student learning. Teach children to read. That is how we tackle society’s inequities.

Now having donned our hair shirts, these conferences have become both our confessional where we plead for forgiveness for our narrow-minded approach and our penance, where we agree to exchange our convictions for anything that will suggest just how broad-minded we now are—as long as we de-emphasize academic goals.

Sitting through the more fiery conference sessions, I could imagine how organizers made some of their panel picks. “Who do we know that has a knack for cutting people down to size?” Many chosen had no educational expertise on offer, but that didn't prevent the smack down. Shame on us, they would extol, for failing to understand the broader impact of poverty and racism on children’s lives. Shame on us for our narrow-minded views of schools as places of mere learning.

The motivation behind some of this vitriol was well meaning. Obviously, the education reform movement was too white for too long. Advocacy organizations have made impressive progress, both in the diversity of who is coming to these conferences and who is given a place at the podium. But why simultaneously try to fracture a movement?

But that’s the impact. We've now all drunk the Kool-Aid and know the new code. Try suggesting to any audience these days that a school’s first obligation to young children is to teach them to read, write, and become numerically literate, and that their teachers should meet a standard that suggests they are qualified to deliver those skills. These academic skills are, if not verboten, now just an aside, emblematic of our once narrow mindset and too closely connected with The Word We Are Not To Ever Mutter Again: TESTING.

It’s a sure way to lose an audience these days to remind them that tests have merit, not just for accountability purposes, not just because they measure numeracy and literacy, but because they are highly predictive of the quality of a child's future. (Thank you Raj Chetty and other academic purists.) A few short years ago, reminding an audience of this connection was a rallying cry. Now our eyes avert, we squirm in our seats, and we feel the sudden need for another cup of hotel coffee.

A broader agenda for education advocates might be more justifiable if we had actually accomplished our more narrow set of goals. By many measures, children's academic outcomes have improved—particularly in the charter schools that this movement created—but the consensus is that progress has either not been fast enough or that it's not even legit. If we agree to expand our role to also tackle the social, economic, racial, and political contexts of students' lives, we'll surely be more successful...right?

There is nothing wrong with any of these goals. They're all good—but their collective impact leaves me limp and rudderless rather than inspired. This job was hard enough.

Achieving a complex, ambitious goal—like providing all children in this nation with a strong education—requires laser focus, determination, abundant resources, an ability to measure progress, exceptional expertise, and a strong research basis. The movement had each of these elements and still does (for the most part). What an amazing asset, not to be squandered or defeated after a few tough battles.

While not shying away from our many imperfections, while recognizing that schools do not function in isolation, we cannot and should not turn our back on what gave rise to this movement.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published on the NCTQ Blog.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

Title I, ESSA, parent engagement. Or just “blah blah blah.” At least that’s what most parents hear when those words get thrown around with zero explanation of what they even mean.

These terms and many others blend into the noise that is parenthood in 2018. It’s our job as education advocates, educators, and policymakers to not just explain but humanize these concepts so that the average parent has the information they need to understand the basics of what is happening and, subsequently, the confidence to engage in a system that can feel overwhelming and even unwelcoming.

And the key to doing that lies in one simple word: relationships.

The 1 percent

Schools that serve a high percentage of low-income students are often referred to as Title I schools because they receive additional federal funds. One percent of these funds, according to past and current education law, must be spent on parent engagement, but we are kidding ourselves if we think parent engagement is about money.

It isn’t.

We are also kidding ourselves if we think that 1 percent of Title I dollars is a lot of money.

It isn’t.

It’s approximately $160 million for the whole country—or a few dollars per low-income parent. So it’s good news that parent engagement is about the relationships that develop between schools, teachers, and parents and not about the mighty dollar. I’ve lived it as a teacher. I’ve experienced it as a parent. I’ve seen it as an advocate.

Luckily, it doesn’t take a lot of money to build better relationships. It does take a lot of hard work. And common sense. And empathy.

Parents, like all people, want to feel noticed and want to know that you care. And as trite as this may sound, it’s the key to increasing—and sustaining—parent energy and engagement in school. And while this desire to be noticed and cared for is universal, it is uniquely crucial with low-income parents because they are the ones who most often feel ignored and dismissed at the schoolhouse gate. They are often seen as the squeaky wheel, but they are rarely the one that gets the grease, largely because they aren’t a constituency that wields power and influence or breeds fear in decision makers.

Former NBA star and Alabamian Charles Barkley recently put out a call to action “to do better for black people and poor white people.”

Barkley’s comments happened to be an admonition to the Democratic Party on the heels of a historic election. But the truth is, his words are a call to action for all of us who care about improving education for all kids. We must do better for our poor students. Period.

Find a common language

For starters, parents can’t take advantage of information that they don’t understand. We know that education-related terms that are second nature to edu-folk are not well understood by parents, and we must invest in changing that. Knowing that parents’ bandwidth for jargon is limited, this will require highly skilled communicators who can break down confusing and wonky language into bite-size chunks that make sense to parents. And it will require messengers who speak multiple languages and can really explain it to parents who can’t engage if everything is in English. In-person exchanges at drop-off and pick-up, back-to-school nights, social media pages, newsletters, emails, apps—there are countless ways to disseminate this information, and all are needed if we are to get closer to a place where schools and parents can speak a common language.

Visit their homes

There is a principal in Providence, Rhode Island, who does something that engages families and tells them, unequivocally, that the school notices and cares. He can often be seen out and about with a staff member during one of their prep periods going to the homes of students who are absent and for whom absenteeism is a concern. If no one is home or no one answers the door, they leave a pre-printed door hanger that not only indicates the number of days missed but also reads in bold letters: “We stopped by to meet with you about your child’s attendance. We want you here at West Broadway Middle School every day. We love you and we’ve got your back!”

This is just one version of home visits, but what all home visits have in common is that they show families that you notice and that you care enough to make time to visit their home and talk about their child. It shows a level of care for the child that many families have never felt from a school before. It helps build a solid foundation on which a strong relationship—a partnership—can grow. Seems like a wise place to invest resources. And time.

And these could also be work visits. Sometimes a parent is so limited in their time off during the day that they can’t make it to the school for a meeting and get back to work in time. This is especially true of parents who are paid hourly and get a finite block of time for lunch and/or breaks. It is also true of parents who do not have a car. Rather than push the meeting off for weeks or months until the parent can come to the school building, take the meeting to them. Every school is filled with cars that just sit in the parking lot all day. Why not use them to help meet parents where they are, not only figuratively but literally too?

Embrace immigrant families

Families who have recently immigrated to the United States describe tremendous anxiety around their children’s homework. Marcela Molina, a Colombian mother of two, says that hearing the words “don’t worry” from her child’s teacher was a huge relief. She wanted the teacher to know that she couldn’t help with analysis of a poem or reading comprehension because her reading level in English is lower than that of her third-grade daughter. She also appreciates when the school shows how much they appreciate the different cultures of the families they serve. Not only do they feel valued as members of the school community, but perhaps more important, the parents see how much the school supports its students learning about and holding on to the identities of their cultural heritage. And Molina’s desire to get involved and actively engage is largely influenced, she says, by school leaders who are highly visible and who are always there with a wave and a friendly “hello.”

Take advantage of phone apps

There are apps that help build bridges and ease communication with families. They don’t take the place of the face-to-face relationship, but they do allow for daily communication between school and home. My youngest son’s school uses one called Class Dojo, described as a “classroom communication app used to share reports between parents and teachers.” The feedback can be in real time and gives parents a snapshot of the day or week that their child has had in school. While many families in Title I schools may not have computer access or even internet access at home, smartphones are ubiquitous in low-income communities. An app that a parent can check on his/her phone can be a game changer.

And speaking of cell phones, some schools provide them to teachers so that communication with parents (and students) can be easy and even immediate at times. I have found it incredibly helpful as a parent, and though I don’t take advantage of it often, it has been hugely valuable when I have. I’ve only seen phones provided in charter schools, but it’s something that should be considered in traditional districts that have identified communication with parents as a major challenge.

Home visits, classroom apps, common language, cell phones—these are ideas that build and strengthen relationships with families. They aren’t a silver bullet, nor are they guaranteed to work. But they are focused on the one thing that makes or breaks school for so many kids: relationships. The sooner we embrace this reality, the sooner we will see real and meaningful parent engagement.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in a slightly different form in The 74 as part of a series on engaging parents and families under the Every Student Succeeds Act.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

Education Week just released its 22nd annual report and rankings of state education systems. Faster than we can read the report or its accompanying coverage—which this year includes a worthwhile look at “five common traits of top school systems” and “five hurdles” standing in the way of improvement—alarmed observations about Ohio’s rankings “drop” have begun to emerge. They point out that Ohio was ranked 5th in 2010, 23rd in 2016, and 22nd in both 2017 and 2018, largely to score political points suggesting that the current administration has been asleep at the wheel.

We’ve been down this path before, but let’s revisit two significant problems with this interpretation. Last year when the ratings were released, I dove into an analysis exploring some of the likely causes for Ohio’s near twenty-slot fall in the relative rankings since 2010.

The rating system changed

Education Week undertook a significant overhaul of its rating system between 2014 and 2015, prohibiting meaningful comparisons of overall rankings over time. They eliminated three categories and now only include the following components: Chance for Success, an index with thirteen indicators examining the role that education plays from early childhood into college and the workforce; School Finance, a grade based on spending and equity, which takes into account per-pupil expenditures, taxable resources spent on education, and measures of intra-district spending equity; and K-12 Achievement, a grade based on eighteen measures of reading and math performance, AP results, and high school graduation.

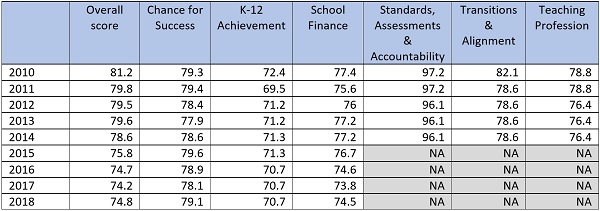

The three categories axed after 2014 included Ohio’s highest-rated areas, Standards, Assessments and Accountability, and two other areas (Transitions and Alignment and Teaching Profession) where Ohio posted solid scores. The table below illustrates how Ohio scored in each category over time and helps explain why Ohio’s absolute score fell given changes to the scoring system.

Table 1: Ohio scores on Education Week’s Quality Counts report card over time

Relativity

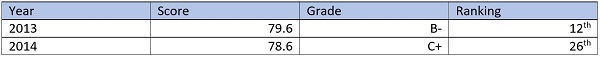

Education Week’s rankings are relative, and Ohio’s shift over time has just as much to do with what other states are or aren’t doing. Last year, I hypothesized that Ohio’s fourteen-slot fall between 2013 and 2014 very likely resulted from the changes rapidly occurring in other states that earned them extra points Ohio had already had under its belt. In fact, the year that its relative ranking plummeted, Ohio’s actual score only changed by a single digit.

Table 2: Ohio’s dramatic rankings shift

Ohio’s actual score changes across nearly a decade among the components that have remained consistent have been fairly modest. For instance, in 2010, the state’s score on K-12 Achievement was 72.4, and in 2018, it was 70.7.

Table 3: Changes to Ohio’s Education Week scores, 2010-2018

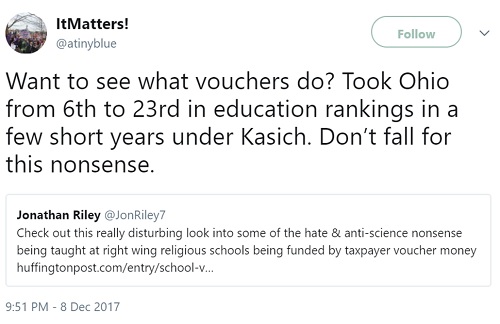

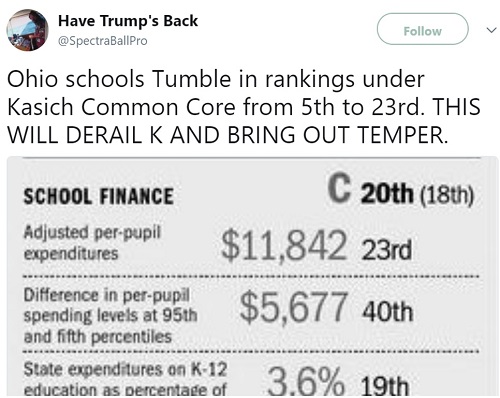

Despite these minor changes in scores, some would have you believe that Ohio’s education system has suffered cataclysmically. As I warned last year, Ohio’s ranking has become easy fodder for those with an ax to grind with the state’s education policies. Unfortunately, that fact remains true a year later. This is not to say that the state’s education policies have been above reproach or that we’re where we need to be. Rather, seeing data used so out of context and without understanding the causes behind such changes leaves us ill-equipped to make meaningful improvements. Consider these tweets that basically assign blame for changes in the state’s ranking to just about anything the tweeter wants to target:

Given how heavily the Quality Counts ranking is cited throughout the year, understanding the finer details of the rankings would likely generate a more productive discussion on how to improve education in Ohio. That is the goal, right?

Is disparate impact analysis an appropriate tool for the federal government to use to investigate school discipline practices? As debate over the fate of the Obama administration’s school discipline policy heats up, expert opinion sharply diverges on this question. Allison Brown and Marlyn Tillman argued recently in USA Today that it’s altogether appropriate. Michael Petrilli argued here in Flypaper that it’s a bad fit. This debate is interesting, but it’s based on a false premise. Properly understood in our nation’s jurisprudence, the Obama Administration’s 2014 “Dear Colleague” letter did not apply disparate impact doctrine.

Disparate impact theory is the notion that an apparently neutral policy that has a disproportionate impact on a particular group may indicate the existence of discrimination. It’s an evidentiary tool, not a substantive standard. Even its strongest proponents would never claim that any policy leading to different outcomes for different groups constitutes unlawful discrimination. It’s hard to imagine how any law could possibly be legal under that standard. It also doesn’t hold that any policy leading to different outcomes is presumptively unlawful discrimination. The rule of law could not possibly hold under the presumption that federal bureaucrats could find virtually any law unlawful at any time.

No, disparate impact theory holds that substantial statistical differences may constitute evidence of discrimination. To determine whether discrimination is actually occurring, investigations must be careful and diligent. But the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) policy put forward in 2014 guaranteed that the investigations would be neither.

The letter correctly cites the three-part test of disparate impact in education set by court precedent in Elston v Talladega:

- The plaintiff must demonstrate that a facially neutral practice has a disproportionate adverse effect on a protected group.

- If the plaintiff succeeds, the defendant must prove that there exists a legitimate justification for the challenged practice.

- If the defendant carries that burden, the plaintiff can still prevail if it’s able to show that there exists a comparably effective alternative practice that would result in less disproportionality (or that the practice was merely a pretext for discrimination).

Suppose under Elston that the school policy said, “a student will get suspended if s/he wears braids.” If the district decided to defend this policy, it might argue that, “while this ban does have a disproportionate effect, it’s necessary to maintain a consistent dress code, which is good for school culture.” A judge may or may not deem this a legitimate justification. Supposing he does, the plaintiff might show that consistent dress could be less disproportionately achieved by a school uniform requirement. Then, a judge would overrule the district. Or perhaps the plaintiff discovers an email suggesting a racial sentiment behind this ban. Then, a judge would overrule the district. All in all, it seems reasonably likely that a ban on hair-braids would not pass a disparate impact test.

But suppose the school policy said a student will get suspended if s/he drops an f-bomb on a teacher. The school would be on pretty firm grounds to argue that there’s a legitimate justification here. The plaintiff might argue that there are other ways to prevent classroom profanity. But, in evaluating that, a judge would (as they did in Elston) give some deference to the school district. He will recognize that the school leaders have years of direct experience serving children. A judge would likely uphold the district’s policy.

But things work quite differently in a court of law than they do in an administrative investigation. Under the 2014 policy, the district has no chance to publicly plead its case, and the investigators need give them no deference. OCR acts as judge, jury, and executioner based on its whim. Or, more accurately, based on what the 2014 letter says.

The letter and its attendant materials make clear, a priori, that no deference will be given—indeed that no good-faith disparate impact investigation will even occur. The answers to questions two and three of the aforementioned three-part test are pre-ordained. Of course there’s not a legitimate justification for suspending students because it’s the stated position of the Department of Education that “suspensions don’t work—for schools, teachers, or students.” And of course there’s a comparably effective alternative because the Department of Education says “there are effective alternatives to suspension,” such as “positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS).”

The “Dear Colleague” letter makes the three-part disparate impact test a farce. There’s only one yes-or-no question: What do your statistics look like? If they show differences, you’re guilty. Just as soon as OCR gets around to telling you so.

Not that OCR need ever issue a verdict. The Sixth Amendment guarantees a right to a speedy trial, but it doesn’t apply to administrative investigations. These investigations drag on for years and end whenever OCR lets them, whether or not OCR ever finds anything.

Oklahoma City’s resolution agreement, for example, belies the notion that OCR uses a legitimate disparate impact test. The resolution finds plenty of fault with Oklahoma City’s statistics. But after two years of investigation, OCR admitted that it never got around to the second or third part of the three-part test:

The District requested to resolve the complaint prior to the conclusion of OCR’s investigation. In order to make findings to conclude OCR’s investigation of this allegation, OCR would have to conduct additional interviews, including interviews with building-level principals and other administrators to discuss their implementation and understanding of District discipline policies. In particular, interviews would need to be conducted to establish whether or not there is a legitimate nondiscriminatory reason for the disparate numbers outlined above.

District-wide investigations are tethered to individual complaints. Did the facts OCR found substantiate any of allegations? No. Not the allegation of race-based harassment, the allegation of retaliation, or the allegation of different treatment. But despite finding no direct fault, and even after two years of investigation, OCR hadn’t bothered to look into whether the district’s discipline policies were justified. Oklahoma City is only unique in that, unlike hundreds of other cases, it came to a “voluntary” resolution agreement to end the investigation. “Voluntary” is a funny word when the process is the punishment, when a federal investigation is the Sword of Damocles requiring endless administrative time and effort to keep from falling.

What have the results of this resolution agreement been? Well, before it was even inked, administrators were boasting that their new policy led to a 42.5 percent reduction in school suspensions. What did teachers have to say? Let’s do something federal investigators never did: listen to them.

Says one:

We were told that referrals would not require suspension, "unless there was blood." Students who are referred do not seem to worry about consequences and are seldom taken out of class, even for a talk with an administrator. There was an instance of a one-day suspension for a premeditated fist fight that occurred as two classes passed each other in the hall. Four students had planned this; one student got suspended for one day. They do not respect consequences.

Says another:

Students have no consequences for their actions. They continue to defy authority and disregard the consequences of their actions. As a new teacher with a new assistant principal, I am having trouble understanding the discipline procedure. It also is very developmentally inappropriate for young children.

Another:

This is the worst student behavior I have seen in over thirty years of teaching. The violence in the hallways is extreme.

And another:

It is amazing the district reports to the local news media that the discipline/referrals issues have gone down when that is not the case at all. Teachers are being abused physically. There is total defiance from students as early as first and second grade.

And yet another:

Student behavior problems are just sent back to the teachers. This year alone a third grade student brought an X-Acto knife to class. The knife was taken by the principal, and the student returned to class. The teacher had to call the parent. This student has also brought a BB gun to school and threatened students.

Another again:

Principals are telling teachers that THEY are being told NOT to write referrals and NO suspensions. This means that teachers must DEAL WITH IT!! Parents don't show up for behavior meetings, so writing B.I.P.’s is a joke. Teachers should NEVER have to choose between defending themselves or losing their job!!!

And, I know this is painful, but just one more:

Students are yelling, cursing, hitting, and screaming at teachers and nothing is being done. But teachers are being told to teach and ignore the behaviors. That is very hard to do now that these students know there is nothing a teacher can do. Good students are now suffering because of the abuse and issues plaguing these classrooms.

What do these teachers think would help? Two thirds want greater enforcement of traditional discipline. As one teacher said, “We need to be able to suspend students for repeated bad behavior. After so many referrals or in-house suspensions they need to be suspended.” Only one quarter of teachers believe in “restorative” interventions.

But, remember, OCR never actually got around to talking to teachers, and the stated position of the U.S. Department of Education since 2014 is that suspensions do not work. The agency doesn’t seem to care what teachers think. OCR investigators certainly could have reviewed the teacher survey and read the harrowing teacher accounts of what was happening in their district because of the federal investigation. But, if they did, it didn’t stop them.

And now, even if Oklahoma City wanted to change course and put student safety first, it might not be able to because it “voluntarily” agreed to “submit any proposed changes to its discipline policies, procedures, and practices to OCR for review and approval prior to implementation.” So, in the rare cases in which OCR allows an investigation to close, whether or not it ever found anything, it retains veto power over the district’s discipline policy.

The “Dear Colleague” letter does not call for investigations based on disparate impact doctrine. It calls for show-trials without the show. Just this week, OCR forced a resolution agreement on Milwaukee Public Schools. According to the superintendent, she had “no choice.” And several school board members stated they had no idea the investigation was happening.

The secrecy of these investigations is why (aside from the fact that it was never actually even used) disparate impact is unsalvageable as a tool for federal investigation into school discipline.

Even if Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos were to rescind the guidance and re-issue a letter that called for a more conscientious application of disparate impact theory, that wouldn’t be enough. Just one vague threatening word from the next secretary and we’ll be back to where we are right now: Districts are presumed guilty and unable to prove their innocence in closed-door pseudo-investigations that maybe not even the school board knows about, while activists applaud manipulated statistics and ignore the voices of teachers and students.

This must stop. And it must never be allowed to happen again. Rescinding the guidance is not enough. Re-issuing better guidance would not cut it. Secretary DeVos should open the official regulatory process and explicitly prevent future administrations from using disparate impact in school discipline investigations. By all means, investigators can and should review data whenever an allegation of disparate treatment is made. But school districts must never again be presumed guilty and unable to prove their innocence, and kids should never again be put in danger because of statistics.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

After losing its sponsorship, ECOT, the largest e-school in Ohio, appears to be on the brink of closure. Districts and other e-schools are bracing for the possible flood of new students, preparing to hire new teachers, manage students’ transcripts, and get them up to speed mid-year. Not surprisingly, politicians are squeezing the situation for every last drop. Taking hardline stances on charter schools in Ohio is like a free campaign booster shot, with this particular situation offering extra potency. Meanwhile, families of some 12,000 students are dealing with the nightmare of impromptu school shopping.

Much is being said about ECOT right now. This shouldn’t surprise, given its status as the largest and most maligned charter school in Ohio and the role of its founder among the old guard of widely reviled campaign contributors in laying the groundwork for a very partisan charter landscape in Ohio. Each development toward ECOT’s downfall has sharpened new arrows in the quiver from which to take aim against charter schools broadly—a serious portion of which deserve never to be mentioned in the same breath as the near-fallen giant. What, if anything, can be learned and applied from this? Here are some takeaways, beyond the most simplistic and/or politicized ones that have dominated news and social media.

- Behind each of these 12,000 kids are parents who will lose sleep. They need better tools. This week, thousands of parents are scrambling to figure out where their kids will be attending school next week. Any parent who’s ever struggled to find a better school option for their kids will understand the gravity of this. Heck, any parent should. This week, I’m thinking about my child’s upcoming Valentine’s Day party, coverage for a sitter, and scheduling a pediatrician visit, and even that can feel like juggling plates. Imagine being a parent who has to drop everything to find a new school. A spokesperson from the Ohio Department of Education suggested that parents review the “find a school” tool on its homepage—a good suggestion, sure, but a terribly inadequate reflection of the work involved to actually do this well. Most families don’t find a school online with the same ease that they find a pharmacy location. And we have a long way to go to make this process easier for families.

- Family choice is paramount. Despite ECOT’s high-profile struggles, it reaffirms the fact that families need better options. Some might suggest the opposite—this demonstrates that the school choice movement has gone awry. Yet regardless of how well ECOT did or didn’t serve its students, the fact remains that many of their students were also ill-served by their previous schools. Parents deserve the right to put their children in options best suited to them—no matter what that means for the traditional districts’ balance sheets.

- And yet, parent choice is not enough. There’s a longstanding debate within the school choice and education reform communities about the extent to whether parent choice must be paired with some degree of government oversight and regulation. ECOT would seem to provide evidence toward the need for stronger oversight—not just on academics but on technical compliance like attendance tracking, which must not be overlooked as it was in Ohio for too long.

- Wide misperceptions on school funding persist. I blogged about this last year, but the headlines about the funding repercussions for Ohio districts continue to seem a bit silly (ex: “ECOT closure could send students and money back to your district”). If more students enroll at a given school, we should expect state funding to follow. However, the notion that districts deserve refunds for students they didn’t educate reflects a misunderstanding of how the funding system works.

- Now would be a good time to revisit your assumptions. No matter your views on school choice or on ECOT in particular, you probably believe those views are aligned with what’s best for children. Rather than reinforce those beliefs and fall headlong into confirmation bias, it’s worth tougher reflection. Charter supporter: Did you ever speak out about ECOT, even when articles like this one emerged about Bill Lager’s remarks about “doing it for the money”? Why not? Were you too worried about sullying the name of charters? Afraid to make enemies within the movement? If Ohio’s charter community had been more unequivocal about quality throughout its history, our narrative may have been different. Charter opponents: What will happen if your district takes on 500 ECOT students who are severely credit deficient? Are you willing to reconsider how you view graduation statistics and how you use them in arguments against charters? Could you stop conflating all Ohio charters with ECOT, calling them for-profit, and using broad brush strokes?

- Precision and data are important. I’ve seen ECOT’s data used in so many ways it’s hard to keep count. It’s an example of the worst graduation rate in the country, yet it also graduates the highest number of students of any school in the state. These numerical sleights of hand happen all the time during policy discourse, yet it’s critical to look beyond headlines and consider data and evidence with nuance.

- We need to do better. Finally, above all else, we need to do better for kids. Every school superintendent, leader, or board member—of any type of school—would be well-served to ask themselves how they can better serve the students they have, including the toughest ones. Especially the toughest ones. In some instances, traditional school districts intentionally pushed out students who were credit deficient and likely to be a drain on their report cards. In other instances, charters have recruited students who are not likely to do well there; this needs to stop.

The fallout from ECOT’s likely collapse should force us all to rethink important education policies, including school accountability for graduation rates, how we document student learning (whether by “seat and screen time” or competency), and even admissions and record-keeping policies. Kids and families in Ohio deserve better than what they’ve been through, and are about to go through, if and when ECOT closes its doors.

How to evaluate teachers is a perennial question that is especially relevant now that ESSA has loosened requirements on state teacher evaluation systems. A recent U.S. Department of Education study examines whether increasing the frequency and detail of written and oral feedback offered to teachers and principals improves teaching practice and student achievement.

The authors studied math and English language arts teachers at sixty-three elementary and middle schools in eight large, primarily urban school districts. Each educator was observed four times a year for two years, once by a school administrator and three times by study-hired observers, followed up each time with an in-person conference, plus a written report with ratings and feedback. The system used to deliver this feedback differed, however, between districts. Four used the Classroom Assessment and Scoring System (CLASS) and four used Charlotte Danielson’s Framework for Teaching (FFT). Teachers also received annual student growth reports that included their value-added scores. Participating principals were evaluated based on twice-yearly teacher surveys examining their instructional leadership and teacher-principal trust.

Both teachers and principals reported finding the feedback more helpful than previous district feedback. A majority of principals described it as more practical and objective, and most teachers found it more specific and useful but also more critical than their district’s, even though more than half the educators received high marks in the study. Participants were less enthusiastic about the value-added growth reports: Only 48 percent of teachers and 74 percent of principals agreed that the value-added score was a good measure of student learning.

The feedback-delivery system also made a difference. When researchers videotaped and analyzed lessons to see how teachers’ practice changed, they found that educators in districts using CLASS improved by 7 percentile points on that rating scale, but found no effect in those employing FFT. Moreover, both helped to identify principals and teachers who needed support, but neither system reliably identified specific areas for improvement.

The interventions also had a limited effect on student achievement. They caused a statistically significant increase in math scores in the first year of the study but not the second, and they did not affect English language arts outcomes at all. There was, however, a positive correlation between achievement in both subjects and classroom lessons that CLASS and FFT rated highly.

In sum, the study’s elaborate observation and feedback systems were expensive and time-consuming, yet produced little effect on student achievement or teaching practices. However, the positive effects on teaching practice under the CLASS metric and the improvement in first-year math scores show that such systems have potential. Clearly, further work is needed to develop observation systems that provide useful feedback and consistent results at a sustainable cost.

SOURCE: Michael S. Garet, et al., “ The Impact of Providing Performance Feedback to Teachers and Principals,” U.S. Department of Education (2017).

As reported by the Dispatch last week, Columbus City Schools has unveiled plans to expand selective admission among its magnet schools next year. This is a positive step in an often criticized district—an effort that should be applauded and helped to grow.

Twenty-five years of school choice in Ohio have largely laid to rest the archaic notion that a home address will determine what schools children will attend from Kindergarten through high school. Interdistrict open enrollment, charter schools, private school scholarships, home schooling, virtual schooling, and independent STEM schools render district boundaries all but irrelevant to parents who are able to navigate these options. Even within districts, specialized schools, programs that look like schools, and lottery-based magnet schools have proliferated, further eroding address-based school assignments and rigid feeder patterns. This is all for the good.

A lesser-known addendum to that list is selective admission, whereby certain schools are allowed to prioritize a percentage of their seats for students who meet particular criteria. Ohio has allowed selective admission—with some important caveats—since 1990, and Columbus City Schools was the first district in the state to make use of this option. Today, five of the district’s magnet schools include a selective admission component: Two are general education and three are arts-focused. All five prioritize 20 percent of their seats for students with strong academic and disciplinary records; the arts schools also require auditions in one or more art forms. If there are more applicants than spots, a lottery is held. The Dispatch story highlighted the waiting lists at all five schools as applicants outnumber available seats—a sure sign of parental interest.

The newly proposed sixth school to adopt this pattern is Columbus Africentric School, a longstanding specialized K-12 school with an immersive focus on African and African-American history and culture. Africentric has recently relocated to a crown jewel of a new facility, and the district is proudly promoting it. Its history of athletic success has traditionally been a big draw, and the school board seems to feel that having a selective concentration of students with excellent academics and good behavior would be another selling point. Thus the district petitioned the State Board of Education to approve it starting next year.

Of course the request should be approved. But why should Columbus (or any district) even have to ask for permission from the state to make this kind of change? Efforts such as this should be a matter of local control, not a state-level decision.

In 1990, concerns about exclusion are what drove Ohio to put this sort of restriction on where and how selective admission could be implemented. The landscape is very different today, however, as more parents demand more and better schooling options for their daughters and sons. In light of this reality, increasing intra-district choice is smart policy. It allows districts to innovate, to create the schools that parents want, and to compete with other schools of choice. It is another break in the "zip code is destiny" approach of yesteryear, an approach that limits kids’ options rather than expanding them. The sooner that approach goes away, the better for Ohio’s children.

Districts shouldn’t have to beg the state for flexibility around admissions policies. Columbus’s initial plan to practice selective admission for 35 percent of the seats in Africentric was reduced by the state to conform to an arbitrary 20-percent limit before the final request was submitted. Who knows better what district parents want and what district schools can accommodate? If that many parents of students with high academics and low discipline want in to Africentric, they should be allowed to do so. Who knows what greater success the five original schools could have achieved had they not been so limited? The existing waiting lists in those schools likely point to the answer.

To be clear, none of these schools are stellar academic performers, and the selectivity being applied is not particularly rigorous. These are not—and should not be confused with—“exam schools” in any way. What they are are better-than-average urban district schools that have drawn plenty of interest from parents and students, most likely because of their alternative focus, boundary-busting admissions, and selective admissions policies (however small that population is). That alone is good news for Columbus and an indication that a new focus on quality could emerge from the status quo. Parents are interested, the school board is all in, and the potential benefits are there. So the state should get out of the way and let the good work proceed.