Editor’s note: This blog post was first published by Partnership Schools.

English teachers everywhere are grappling with how to take their discourse heavy classrooms digital. We believe that first principles for meaningful and rigorous English instruction are as practical for students learning at a distance as they are in the classroom. While it might be tempting to reinvent your style as we all go remote, we’ve encouraged our English teachers to keep it simple. Specifically, we’ve centered our core essentials for effective English language arts instruction and made a few adaptations for teaching remotely.

Start with rich, complex texts. While it might be tempting to lean on more simply written or “high-engagement” reads in this era of remote learning, we believe students should continue to read rich, complex texts that will challenge them as readers and substantively broaden their knowledge base. Our very own Seamus Ronan sent his eighth graders home with a retired class set of Jack London’s consummate Call of the Wild—and we love this pick!

To be sure, scaffolding these texts may look different when you’re teaching remotely, but we shouldn’t compromise on giving students rigorous texts worth reading. For example, you might balance students’ independent reading with listening to the text and reading along. This helps students develop an ear for the tone and narrative style of the text, while keeping the thread of the narrative moving along at an engaging pace.

Assign daily pages. It’s just not about volume. It’s about prescribing a healthy dose of reading that students will do with consistency and undivided attentiveness. Assigning a manageable set of pages for daily reading gives students the routine they crave and the satisfaction of completion at the end of every day.

Provide parameters for reading. Offset the complexity of texts with focal points for each set of pages that students are assigned. Explicit framing is especially helpful for struggling readers. Choose to call their attention to the details that students must be attentive to in order to produce a deep, meaningful interpretation (e.g. the appearance of motifs, the development of a theme, an allusion to an important historical event, etc.).

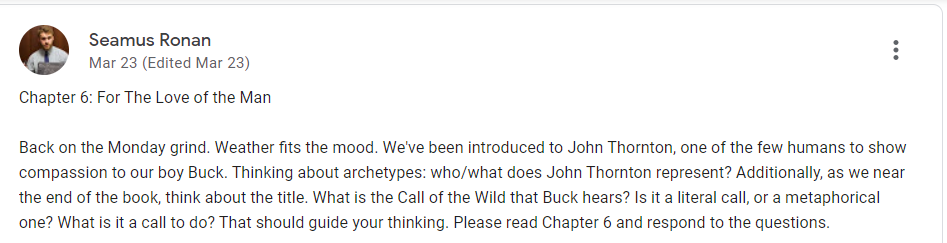

Here’s an example of Seamus’s framing of a chapter from Call of the Wild for his eighth graders:

Create a daily question. As we teach remotely, it’s important to accept that we can’t delicately unpack every beautiful moment from the text we choose. Instead, our planning goal is to create one really, really good, thoughtfully crafted question a day for every student to respond to.

Here’s one Seamus wrote for Call of the Wild:

On page 99 (of my version), London writes, “Mercy did not exist in the primordial life.” What does that mean? Why do you think this is? Give an example of how mercy does not exist in The Call of the Wild.

We love that Seamus has put intense focus on a single line that is emblematic of the novel. If a student remembers this line and their own analysis of it ten years from now—that will be a momentous win.

Critically, his question is also text dependent. It asks students to not only establish the meaning of what they’ve read, but also analyze it. (For more on this, visit Doug Lemov’s Field Notes.) Students can’t answer it successfully having only gleaned the “gist” of the narrative. Better yet, many students will go back and reread pivotal moments from the novel as they formulate their interpretation—a great habit to socialize in all readers.

Prioritize bite-sized feedback: Engage with student thinking as you would in the classroom. Seamus uses Google Classroom so that, as answers flow in throughout the day, he can respond to each comment. If you are more inclined to go low-tech, you could ask students to snap a picture of their writing and email it to you so you can reply once a day.

Whether the student was far afield or nailed it on their first try, strive to make your comment authentic and useful. You may want to help them lock in a key idea they’ve missed or stretch their initial answer to greater levels of sophistication and complexity. But remember, quality beats quantity. Regular bite-sized feedback helps to keep students thinking deeply and provides them an important sense of connectedness.

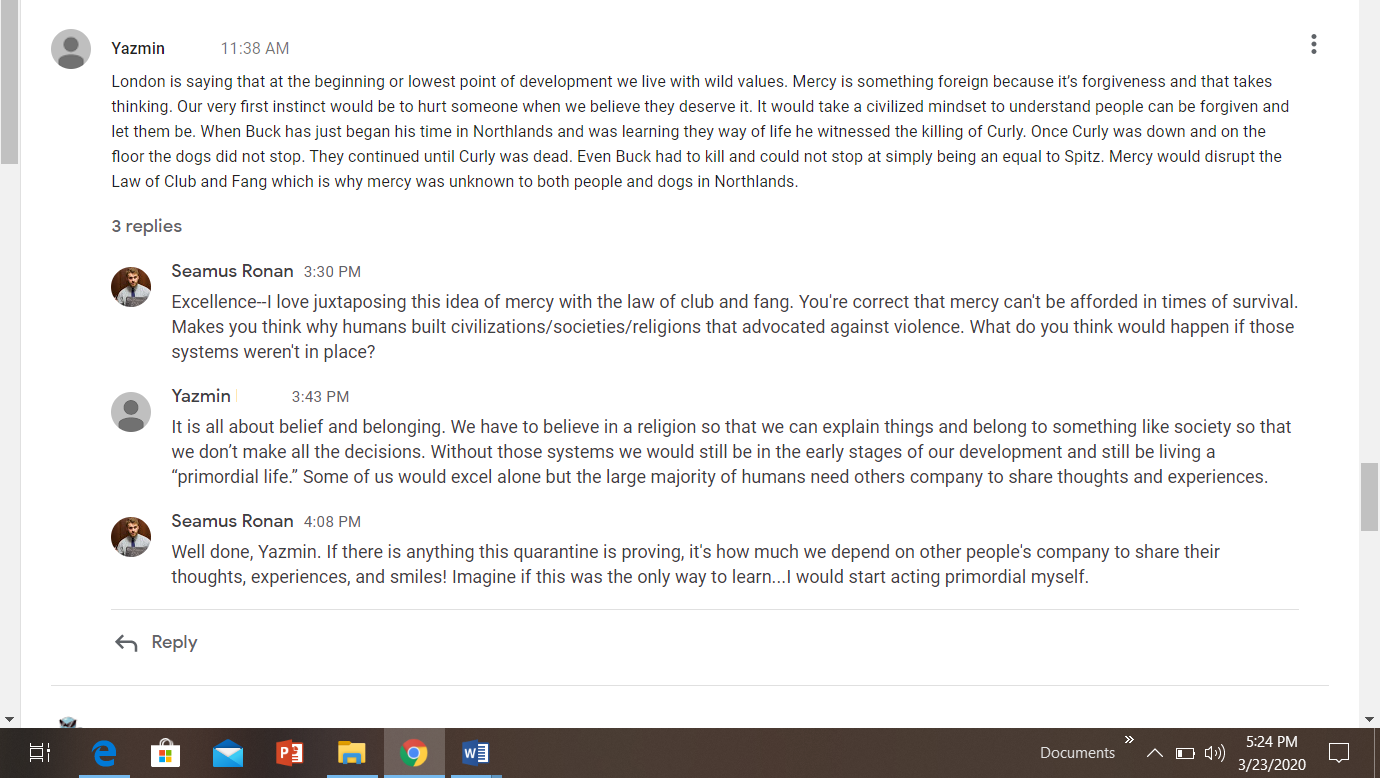

Look how Seamus rewards Yazmin’s strong initial response with a second, more challenging question:

Lastly, vary the routine … but thoughtfully. Once students have gained traction in the text, spice it up! Assign primary texts to build relevant knowledge and help them understand the novel more deeply. Maybe prescribe a little “Close Reading.” Or introduce useful or domain-specific vocabulary for them to apply in their analyses. All of these things can be layered on to compliment your elegant routine, but don’t overdo it with bells and whistles that may distract from the core goal of reading a tough novel really well.

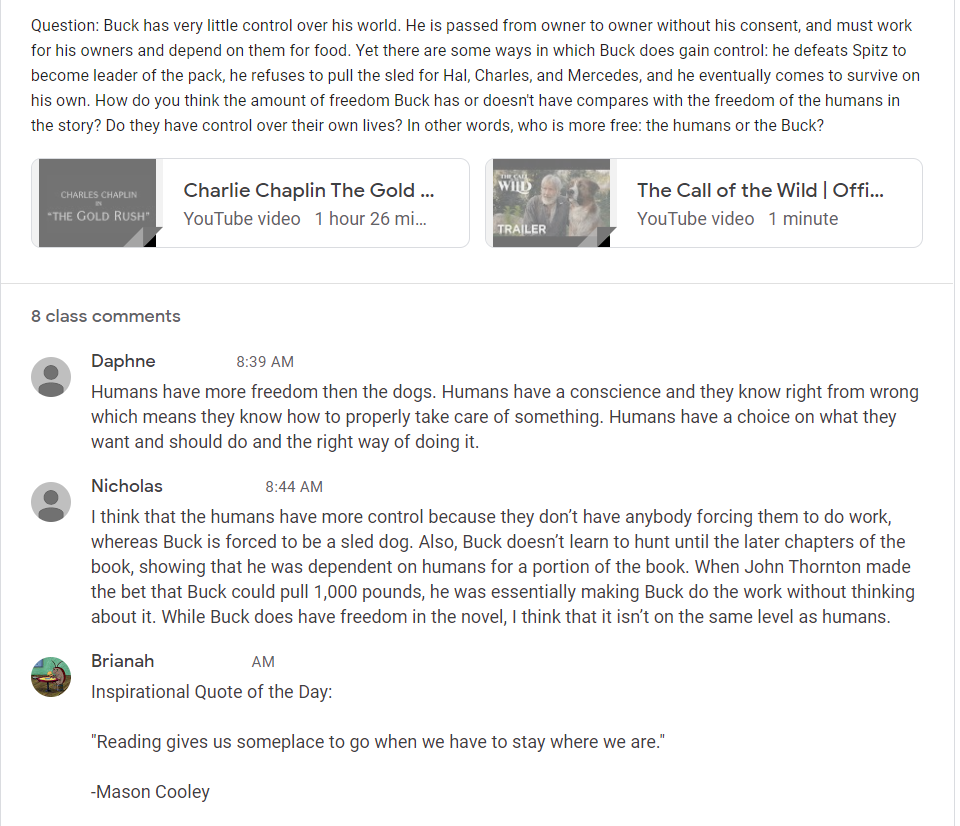

Having carefully chosen Google Classrooms as his sole digital forum, Seamus’s students have mastered the technology. Now, Seamus has begun tasking them with responding to each other, making their shared reading feel more like a classroom discussion. Take a look at how his students are beginning to run with it:

Brianah’s interjection says it all. This wonderfully straightforward routine has helped Seamus’s students escape into reading and truly enjoy it, while he keeps the bar for their intellectual work unapologetically high.

—

The good news is that even if you haven’t sent your students off with a tried and true novel, there is an abundance of free novels, poetry, and primary texts now available digitally. We suggest you start with Common Lit, Tumblebooks, or Get Epic and take your pick. And as you make your choice, don’t forget the importance of choosing complex texts for all of our readers, even our littlest ones, to grow against.