Getting advanced learners (a.k.a. “gifted” students) the education they need, and ensuring that this works equitably for youngsters from every sort of background, is substantially the responsibility of state leaders.

Districts and individual schools, charters included, do the heavy lifting, but states create the policy structures (and funding flows) within which this happens. They create guidelines for which students are eligible, how they should be identified, what services must be provided for them, how to track their progress and the performance of their schools, what qualifications must their teachers possess, and how to ensure fairness across the board.

Today, sadly, America’s high-flying students—and those with the potential to soar—face a dizzying array of inconsistent and incomplete state policies and practices. This is meticulously—and depressingly—documented in the National Association for Gifted Children’s “State of the States” report. Working through its tables and analyses yields much insight into what a jumble is this policy domain between states—and how inconsistent many states are within their own policies.

In Fordham’s home state of Ohio, for example, statutes supply a reasonably clear definition of who’s eligible for “gifted and talented” education, a mandate for their identification, and guidance as to what methods should be used to identify them. The Buckeye State also does a credible job of tracking the achievement growth (on state assessments) at the school level of those who do get identified, and it reports how many within that population actually receive some sort of extra services from their districts. Good start, sure.

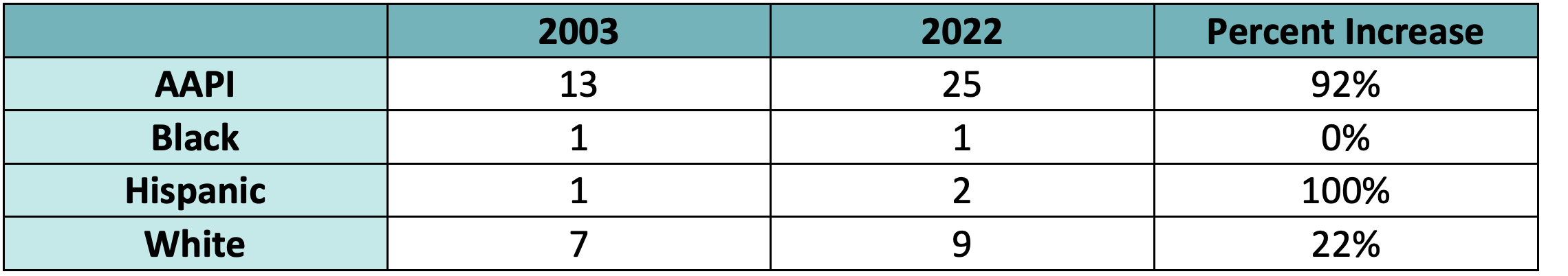

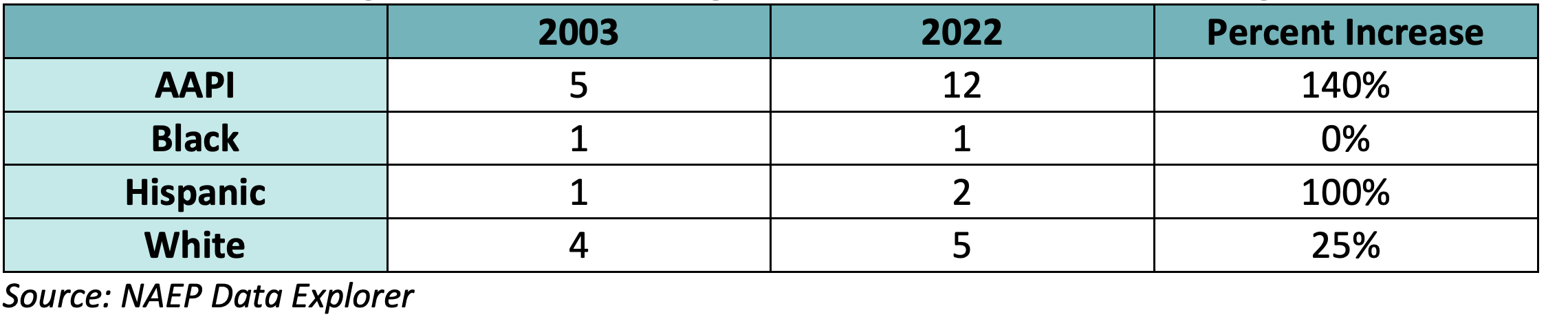

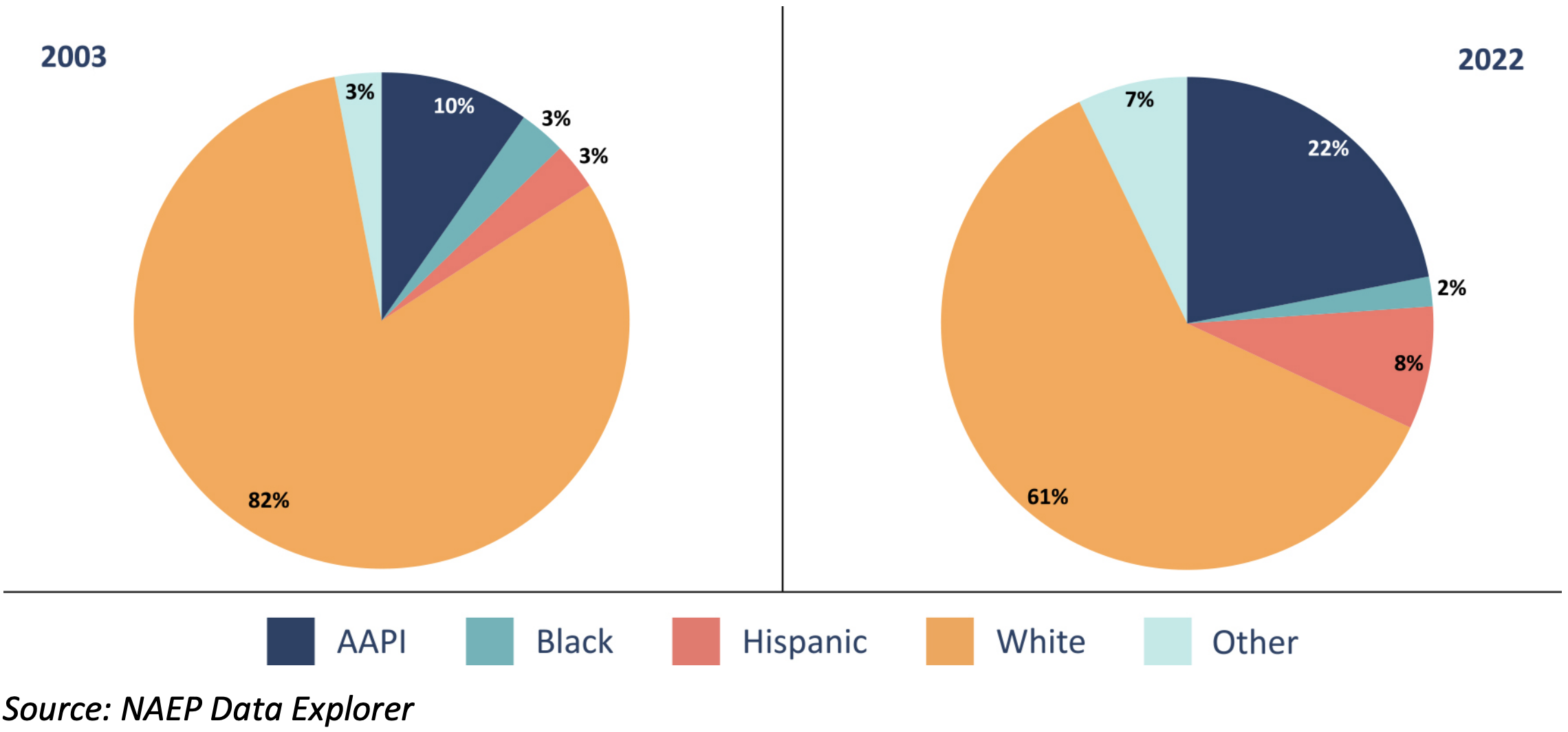

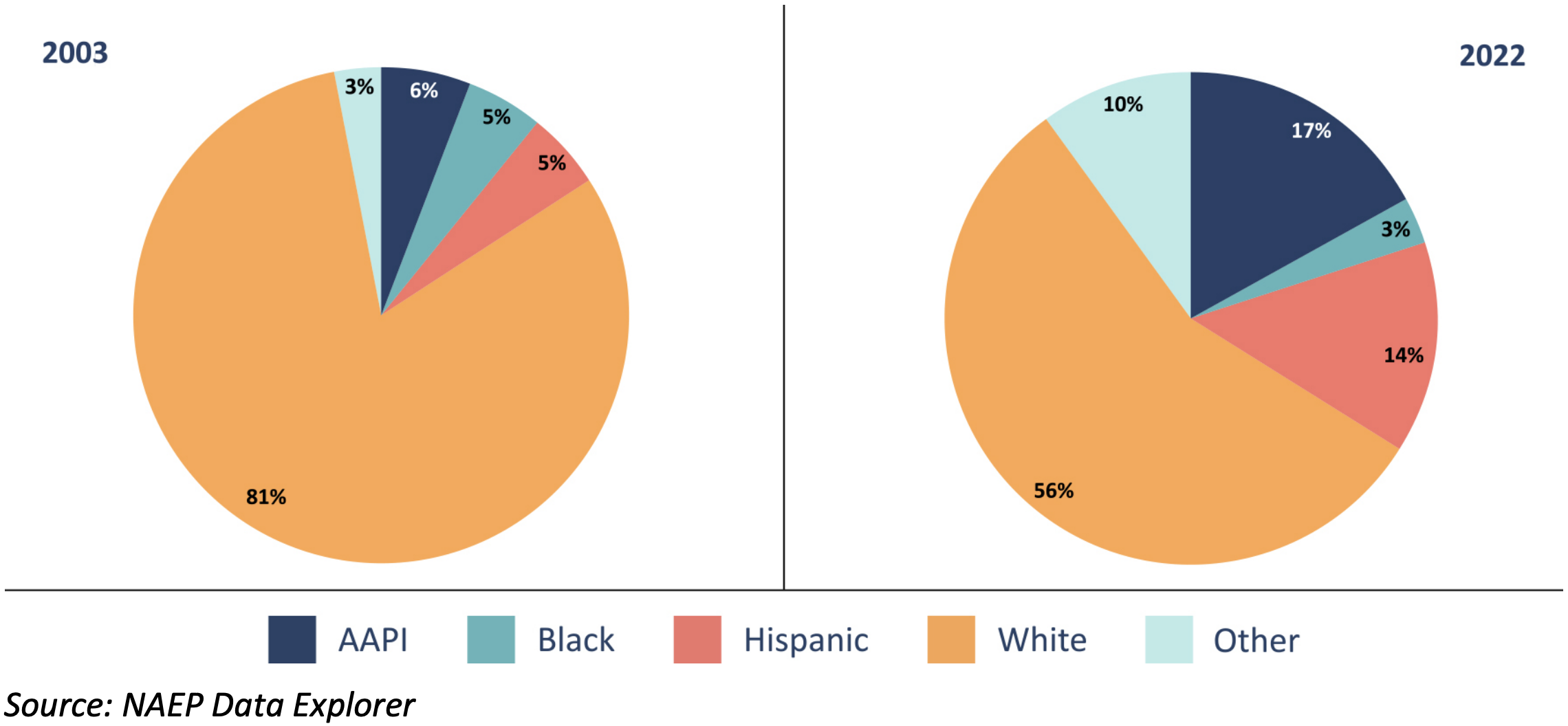

Yet Ohio has absolutely no requirement for serving those kids, i.e., nothing that obligates Buckeye schools to do anything different for their advanced learners at any level—not elementary, not middle, not high school—let alone any mechanism for ensuring equitable participation. As a result, just 5.2 percent of those identified as “gifted” in Ohio are Black and 21.4 percent come from low-SES families (these data are from 2020–21), though the state’s public-school population that year contained approximately 16.8 percent Black youngsters and 48.4 percent from lower-SES households. Unsurprisingly, Ohio loses large quantities of high-potential human capital—and does far less well than it might on upward mobility—by virtue of the fact that gifted poor kids are much likelier to “lose altitude” as they pass through school than their more prosperous peers.

What, then, should state leaders do—assuming, as we should, that they care about giving every child the fullest and most challenging education that those youngsters can effectively use, developing their state’s human capital, deploying rational policies, and narrowing the yawning “excellence gaps” that exist today?

Rejoice! An answer is at hand. They should turn to and follow the useful nine-part policy roadmap for state leaders that was recently developed by the National Working Group on Advanced Education in its excellent report, Building a Wider, More Diverse Pipeline of Advanced Learners.

Here’s the plan—noting up front that all nine of these steps must be taken in synchronized fashion. It’s not “pick and choose” your policy—or today’s chaos will persist.

First, in their school and district accountability systems, states should place significant weight on student-level progress over time, not just grade-level proficiency, so as to encourage all schools to help all students achieve their full potential, including high achievers. When all the focus is on getting kids over the proficient bar, those who have already cleared it may be ignored.

Second, states should eliminate any policies that bar early entrance to kindergarten, middle school, or high school. This allows high performers to start sooner, move faster, and get farther.

Third, states should mandate the use of local, school-based norms for identifying students for advanced programs, in particular at the elementary level. That means that every elementary school in the state should have a “gifted program” of some kind, serving at least the top 5 or 10 percent of its students or ensuring that they’re well served elsewhere.

Fourth, states should implement specific requirements about the services provided to advanced learners, services such as achievement grouping, accelerated learning, serious enrichment, specialized schools, and more. Too many states—as in the Ohio example above—require identification but nothing to ensure that those who get identified will get the schooling they need.

Fifth, states should mandate that districts and charter networks allow for acceleration (including grade skipping) for students who could benefit from it, and should clarify that middle school students who complete high school courses can earn high school credit.

Sixth, state should publicly report on the students participating in advanced education, including their achievement and growth over time, as well as their demographic characteristics.

Seventh, states should ensure that preparation and in-service professional-development programs offer evidence-based instruction in advanced education, both for district-level coordinators and for teachers.

Eighth, states should enforce the federal requirement that states explain how teacher-preparation programs address education of special populations, including advanced learners. (Today, this is a requirement for Title II reports that is widely ignored.)

Ninth and finally, states should provide funding and other incentives to encourage schools to frequently and equitably evaluate all students and provide a continuum of services to every student who could benefit.

Take that list to heart, state leaders, put its precepts into practice—all, not some of them, and in time your state will do right by its advanced learners, strengthen its economy, encourage upward mobility, and boost equality of opportunity.