When we talk about high standards, accountability, and school choice, one essential element is often overlooked: giving parents and education leaders information they can actually use. It’s one thing to produce data, but quite another to make it useful—easily understood, comparable, and actionable.

The District of Columbia has reaffirmed its commitment to making good data available in its second annual publication of Equity Reports. These reports provide unprecedented levels of information on how well each public and public charter school in the District of Columbia serves all students. By providing apples-to-apples comparisons of schools and presenting the results in a format that is easy to understand, the reports signal potential problems, help school leaders focus on areas where schools need to improve, and guide parents as they make decisions about their child’s education.

This is an important step in addressing some of the most critical issues about equity in public education: How successfully are we closing the achievement gap between black and white students, and between low-income and more affluent students? Are we suspending children of color at higher rates than white students? How well are we serving students with disabilities? These data will lead to tough and important conversations at schools and around the District as we dig into the underlying causes of the results we now are able to see.

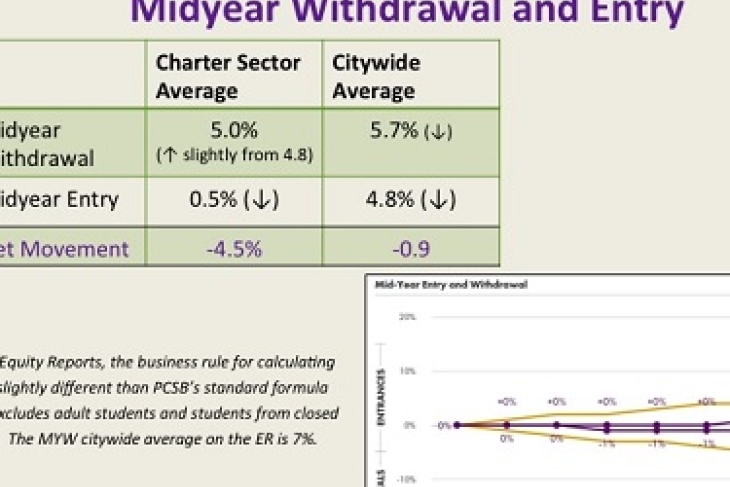

Moreover, our Equity Reports tackle perennial charter school pain points head-on: Do charter schools push students out mid-year? Do they accept students all year, in all grades? Are charter schools serving fewer special needs students? Addressing these issues is particularly important in a city where charters now serve 44 percent of students.

Having learned about the concept from our friends in New Orleans, the D.C. Public Charter School Board (PCSB)—the sole authorizer of charter schools in the District—introduced Equity Reports here. Leaders in D.C. Public Schools and in the city government embraced the idea and, together, we have made it a district-wide effort. But writing a report must also galvanize action that leads to policy changes. Among the findings:

Transparency surrounding difficult issues leads schools to improve their performance without resorting to additional regulation. Each charter school has its own independent board whose members historically have relied on their school leadership to tell them how things are going. Now board members can see, for example, that English learners had far lower academic growth than the school as a whole, or that the school suspended students with disabilities at three times the rate of other students. Schools use this data to prioritize these issues, and their responsiveness produces results. Many schools, for example, have instituted restorative justice programs to reduce suspensions and expulsions. Since we have begun publicizing equity data, expulsions in charter schools have been halved, and suspensions are down 20 percent.

Equity Reports dispel charter myths. It was “common knowledge” that charter schools didn’t serve the highest-needs special needs students; this data shows otherwise. Charter schools serve the highest-needs special needs students at slightly higher levels than traditional public schools. And everyone “knew” that charter schools suspended too many children. But again, these reports show overall suspension rates for black and low-income children are below city averages. Then there was the persistent myth that charter schools forced children out right before statewide testing. Now that we show withdrawals month by month for each school, everyone can see that this does not occur in any D.C. charter school.

Equity reports provide parents more information to help them make the right school for their child. That’s important in D.C., which is one of the five top cities for school choice. Parents can only make good choices when they have good information, and our equity reports provide the most thorough and accessible information about school performance and climate anywhere in the country.

The day-to-day work that went into producing the Equity Reports led charter and traditional public schools to work closely together, solving problems and harmonizing data collection. For example, we learned that DCPS counted a student as present using different rules than charters, and we made the rules uniform. We agreed that in-seat attendance (which ignores whether or not a student has an excuse) was a better predictor of student success than truancy rate (which only counts unexcused absences). That kind of collaboration helps build bridges between charters and traditional public schools; it drives progress for the benefit of all children.

D.C.’s Equity Reports are promoting transparency, equity, autonomy, and choice by providing unprecedented data about school performance and making it easy for all to see and compare. LEAs, school districts, and charter authorizers ought to take a look at D.C.’s equity reports and consider whether their local parents and education leaders would benefit from having similar clarity about their own schools. Any school district seeking to drive improvement through school autonomy would do well to consider this approach.

Scott Pearson is the executive director of the D.C. Public Charter School Board. The board is responsible for academic achievement for the 112 public charter schools in Washington, D.C.