Oh, how I would welcome and laud a nationwide education regime in which every high-ability student has access—beginning in Kindergarten—to teachers and classrooms ready and able to expedite and accelerate that youngster’s learning; in which every child moves at her own best pace through an individualized education plan and readily gets whatever help she needs to wind up truly college- and career-ready, whether that happens at age fifteen, eighteen, or twenty-one; and in which every teacher possesses the full range of skills and tools necessary to do right by every single pupil for whom he is responsible, regardless of their current level of achievement.

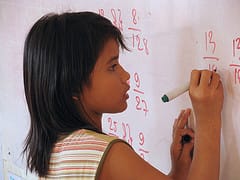

Millions of high-ability, academically promising youngsters are not receiving the challenging education they need to reach their maximum potential. Photo by mrcharly |

That’s what we should aspire to—and work to make happen. Alas, that’s not how many places currently function. Among the victims of our present dysfunction are millions of high-ability, academically promising youngsters who are not getting the kinds of “gifted-and-talented” education that would likely do them the most good and help them to realize their maximum potential. (Collateral victims are a society and economy that thereby fail to make the most of this latent human capital.)

There’s no agreed-upon definition or metric for “giftedness,” so there are no truly satisfactory data on how many such youngsters reside in the United States. But assume, for this purpose, that we’re talking not about rare geniuses and prodigies but about the “talented tenth,” the one child in ten with the greatest potential for high-level cognitive achievement. That would translate to about 5.5 million girls and boys.

Nobody today can tell us how many of these kids actually make it into gifted-and-talented programs and classrooms, Advanced Placement (and International Baccalaureate) programs, specialized “exam schools,” and the myriad but motley other special offerings that do a decent job of serving such youngsters. (One encouraging datum: The College Board reports that 18 percent of 2011 high school graduates earned a score of 3 or better on at least one AP exam during their high school careers.)

States, districts, and individual schools differ dramatically in terms of the arrangements they make for such students, the extent and accessibility of their offerings, and the mechanisms by which they do and don’t successfully identify high-potential kids. Not many of them, however, are well-disposed towards creating separate classes, courses, programs, or schools for such youngsters—nor towards “ability grouping” them within schools and classrooms. Indeed, the education fraternity is dominated by the twin beliefs that “tracking is evil” and that “smart kids will do OK regardless.” The same fraternity is also under considerable pressure from federal and state policies to focus attention and available resources on low-achievers. As a result, high-potential kids are often neglected.

Insofar as teachers, schools, and programs do exist for them within U.S. public education, it’s well known that children from middle- and upper-middle class families with educated—and education-minded—parents are most apt to take advantage of such offerings and that poor and minority youngsters, particularly those without a lot of educational sophistication at home, are least likely to. Here is how the College Board frames the problem:

Hundreds of thousands of prepared students were either left out of an AP subject for which they had potential or attended a school that did not offer the subject. An analysis of nearly 771,000 graduates with AP potential found that nearly 478,000 (62 percent) did not take a recommended AP subject. Underserved minorities appear to be disproportionately impacted.

This is a great shame, of course, but it’s not exactly a surprise that more affluent kids are likelier to end up in gifted programs. Their families don't face the stress of poverty, and they tend to have two parents who read to their children, send them to preschool, etc. The socioeconomic achievement gap (see Mike Petrilli's appearance in Dr. Josh Starr's podcast) is well documented—and a corollary of it is that kids from more fortunate circumstances are more apt to end up in gifted classes. (Note, though, that Jessica Hockett and I found almost the same proportion of low-income youngsters in the country’s handful of “exam schools” as in the broader high school population in our book Exam Schools: Inside America's Most Selective Public High Schools.)

The problem begins well before high school, of course. Indeed, for many youngsters it begins at home in the early years, leading to ill-prepared (though possibly very bright) kindergartners and first graders, then to middle schools with gifted-and-talented classrooms dominated by kids whose parents did prepare and push them—and helped them navigate complicated access arrangements.

The New York Times on Sunday made a huge fuss about this as it plays out in our largest city—specifically, in a K–5 school on Manhattan’s Upper West Side that is 63 percent black and Hispanic but in which such kids comprise only 32 percent of the enrollment in the gifted classes.

Following standard Times (and Upper West Side) ideology, reporter Al Baker chose to focus on the city’s mechanisms for screening and selecting kids for entry into its gifted programs (and high-powered high schools, etc.). The burden of his article is that New York’s education department discriminates against “children of color” via selection mechanisms that result in white (and Asian) youngsters receiving the best odds of accessing such programs and schools.

One may well yawn because this is so predictable a perspective. It’s also the wrong perspective. We might first acknowledge that many urban school systems would be thrilled—and praised—if a third of the kids in their gifted classrooms were black and Hispanic. But the more important point is that the supply of such classrooms is skimpy almost everywhere and America’s entire K–12 education enterprise does a lousy job of identifying and cultivating high-ability kids whose parents (for whatever reason) are not prepping and steering them into the available seats in such classrooms.

We’d be outraged—as would be the Times —if we learned that there weren’t enough special-ed classrooms, teachers, or programs to accommodate the population of children with disabilities. (Indeed, a big problem in the special-ed realm is over-identification of such kids.) But when it comes to high-ability students, instead of lamenting the under-identification challenge and the dearth of suitable classrooms, teachers, programs, and outreach efforts, the Times—and a lot of others—settle for playing the race card.

Shame on them.