Today, the Senate HELP Committee is considering the bipartisan ESEA reauthorization bill crafted by Senators Alexander and Murray.

This legislation represents a very smart compromise on the key issue of accountability. What happens in committee, on the floor, and beyond is anyone’s guess. But the current language is, in my view, the best proposal we’ve seen for solving the problem that’s held up ESEA reauthorization for ages.

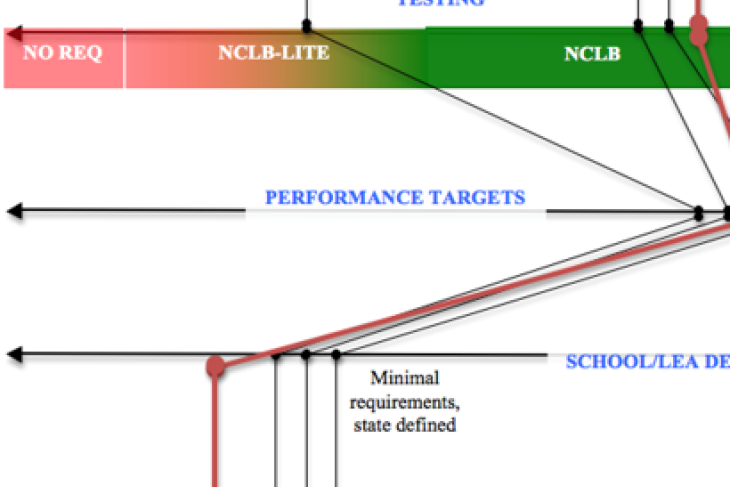

In February, I created a graphic showing how the various proposals on the table handled the various elements of accountability. The major plans followed one of three approaches. The middle path (between a beefed-up federal role and an emaciated one) was staked out by state-oriented groups including CCSSO, NGA, and NCSL. I called this “Accountability for Results.”

The Alexander-Murray bill is in this mold, though with a couple of notable adjustments.

Like many other plans, it keeps NCLB’s suite of tests. But it makes a very important, very interesting, and very compelling amendment to NCLB’s aspirational target of all students reaching proficiency in each grade by a certain date. Instead, it requires states to create accountability plans so that all kids are on track to reach college and career readiness by high school graduation.

This approach ensures that we continue focusing on the needs of all kids. It also maintains a high bar for achievement (postsecondary success). And by putting the ultimate performance target at the end of students’ K–12 careers, the legislation gives states, districts, and schools a full thirteen years to make up the academic gaps students entered school with. In this sense, the bill sets an absolutely reasonable quid pro quo for $15 billion in annual federal Title I funds: Get kids ready for postsecondary education or work.

So how does the legislation intend to have states achieve this goal? By setting them free of NCLB’s other major accountability rules. States can create accountability systems with performance indicators of the states’ choosing. Those systems will determine how to identify schools for increased attention, how many schools need interventions, how to help struggling schools improve, and more.

This bill is tight on ends and loose on means.

In my view, the biggest concern is whether its accountability provisions are strong enough. For example, one could argue, with some justification, “Under this legislation, states could set the target date of postsecondary readiness at 2075, the secretary of education would be banned from doing anything about it, and there would be no clear consequences if the state fails to make even this minimal progress with its kids.”

I suspect that issues related to secretarial authority and the role of peer review in state plans will be raised in the committee markup and on the floor.

But I also think that this legislation would simply force these kinds of debates back to the state level, where they belong. In other words, education advocacy groups should start to direct their attention to who gets chosen as state chiefs, what’s in state accountability plans, and how much progress states are making. And if this new approach doesn’t work, the next reauthorization of ESEA—hopefully in five years, not fourteen—can make the necessary adjustments.

The criticism of the bill I have a harder time understanding is the kind offered by Mike yesterday. He is concerned this bill would put “enormous pressure on the states to set utopian goals,” the type that undermined NCLB. Given our nation’s longstanding inability to get more than two in five high school graduates prepared for college, Mike argues that we’re setting states and schools up to fail by establishing postsecondary readiness as the target.

Personally, I don’t think it’s unreasonable to ask states to graduate students who are prepared for education and work beyond twelfth grade. That’s why we have primary and secondary schools.

We should also acknowledge, however, that many students enter school far behind their peers—and that catching them up can be very tough work.

But a great strength of this legislation is how it enables states to demonstrate that these two things can be squared. In short, by putting the target at twelfth grade and allowing states to make full use of “growth” measures, the bill essentially says, “We expect all kids to be ready for graduation, but you have their entire primary and secondary careers to get them there and the authority to decide how to do it.”

In my view, this represents the proper understanding of “student growth” in accountability systems. That is, it should never be enough to simply say kids are making progress. We should aspire to have them make progress toward a specific target, a goal that will be prepare them for lifetime success.

In total, this legislation empowers states by getting “tight-loose” right; it sets a high bar for achievement; it focuses on the needs of all kids; and it allows schools to get credit for student progress toward a clear goal.

This is very smart legislation.