In The Atlantic this week, Carly Berwick praised Germany for raising its nationwide test scores while simultaneously reducing educational inequality. That’s no small feat—and one well worthy of recognition and accolades. Indeed, in our recent book, Failing Our Brightest Kids: The Global Challenge of Education High-Ability Students, we reported the same dual accomplishment in the Federal Republic. But we also pointed to a few weeds among these roses—namely Germany’s bright students, who aren’t enjoying any of these gains.

Much like the U.S., Germany has a decentralized education system—with sixteen Bundesländer that resemble American states in the ways they shape and pay for their school systems. This system was fairly static—and complacent—through the twentieth century. The economy was strong, east-west reunification was succeeding, employers and unions made decisions together, and the integration of vocational schooling with apprentice-style training produced a well-functioning workforce.

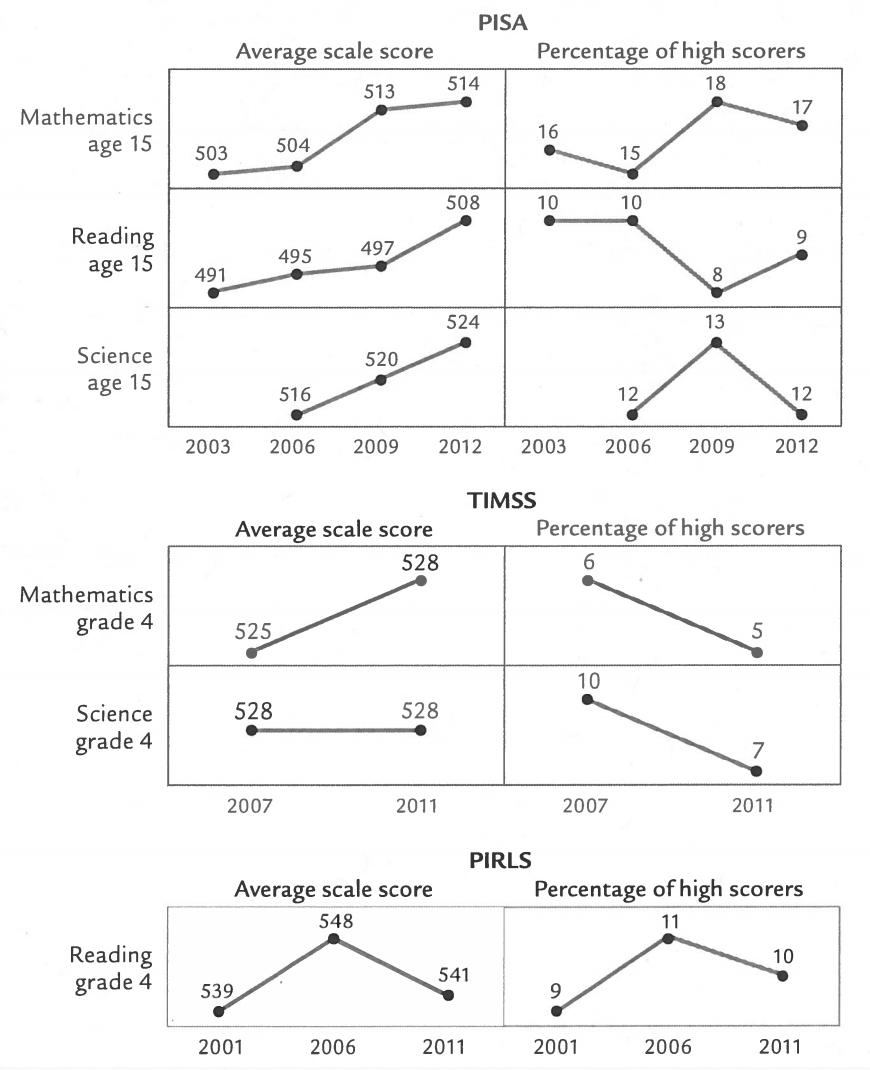

Then came what some Germans call the “PISA shock” of 2001. Much like the U.S. reaction to A Nation at Risk in 1983, residents of Germany were stunned to learn from their first Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) data that their children were scoring well below the OECD average in reading, results that had been foreshadowed, although less noticed, by disappointing math and science scores on the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) a half-decade earlier. The PISA data—underwhelming for those two subjects as well—also showed that achievement and career opportunities were far from equal, especially for poor and immigrant youngsters and those not fluent in German. Academic standards varied widely across the country, and few fifteen-year-olds reached the ranks of top scorers. Much debate followed and then, slowly, a series of reforms were launched, many of which are still under way.

The national government brokered a move toward common curriculum standards (as well as more preschool), but in most realms the länder did their own thing. Many of them extended Germany’s notoriously short school day and strove to boost teacher quality. Schools were given greater autonomy in return for more accountability. And rigid tracking was eased so that the post–primary education paths incorporated ways to shift among them if one’s interests or career plans changed.

It worked, too, much as Ms. Berwick pointed out in the Atlantic. Gains began to appear on PISA in 2009, primarily in math but also visible in reading and science, with fewer weak achievers and improvements among disadvantaged youngsters and immigrants. The correlation between low scores and low socioeconomic status has definitely weakened.

At the high end, however, Germany cannot boast much improvement, as this figure shows. Since 2009, aside from PISA reading, the percentage of German top scorers has dropped in every math and science measure across age groups—fourth grade, eighth grade, and age 15—as well as fourth grade reading.

Germany’s average scale scores and percentiles of high scorers on international assessments over time

Why aren’t smart kids in Germany sharing in the gains? This being Western Europe, a strong social norm favors equality, and people are uneasy about singling anyone out as better than anyone else. This being Germany, with its troubled history, it’s even less acceptable to suggest that a person is in any way superior. And nobody in the education sector there wants to be seen as elitist (although business leaders are less skittish).

Attitudes and practices toward gifted education also vary by länder and there’s no national strategy in this realm. And perhaps many parents are not aware of the children’s potential, don’t know about the available education options, or don’t want to take advantage of them

At the primary level, inclusion remains the watchword in German education and, while teachers are urged to differentiate their instruction, little effort is made to prepare them to do this for high-ability students. Various supplemental programs are available for such children, yet this feels half-hearted. At the secondary level, a handful of gymnasia (high schools) offer terrific “fast-track” options for gifted pupils, but their scale is small for so large a country and entry into them relies more on IQ-type testing than on children’s past performance or other evidence of potential. On balance, it appears to us that, while the “PISA shock” has indeed prompted worthy changes at the low end of German education, it hasn’t yet made much difference at the high end.

This is a problem. It’s also a problem when close looks at a country’s educational performance ignore what’s happening at the high end. That’s at least as much of a problem in the U.S. as in Germany—which is why we wrote our book. If we can’t do a much better job of solving it, the U.S. won’t achieve either excellence or equity. It will put itself at greater economic risk by robbing us of tomorrow’s scientists and entrepreneurs. And it’s especially cruel for high-ability poor children who are best positioned for upward mobility if only the education system will assist them to realize their potential.

So, yes, let’s applaud Germany for raising its scores and reducing inequality. The U.S. is trying to do that, too, and it’s important that we continue. But we must be wary of policies that raise the floor while ignoring the ceiling. Germany might want to consider that, too.

Wavebreakmedia/iStock/Thinkstock