Editor's note: This post is the first entry of a three-part series on Race to the Top's legacy and the federal role in education. You can read the final two entries here and here.

Secretary Duncan’s resignation announcement produced less commentary on Race to the Top (RTTT) than I expected. I was hoping for more.

Though they’re now out of vogue, I’m still open to federal competitive grant programs, and I’m trying to decide when they’re appropriate and what form they should take. I also have some personal interest in the program. In 2009–10, I spent an inordinate amount of time analyzing applications and writing about the competition. As a state official in 2010–12, I worked on a RTTT grant.

This gigantic program—and the era with which it’s associated—deserves scrutiny. We ought to ask ourselves how this experience should inform future federal policy making.

William Howell’s Education Next article “Results of President Obama’s Race to the Top” is a good place to start. Howell marshals new evidence, showing the overlap of the program’s lifespan with an era of lively state-level policy change.

But I think Howell overstates RTTT’s influence. The analysis gives the federal government more credit than it deserves and, more importantly, fails to adequately recognize that the program stood on the shoulders of twenty years of state and local effort.

An uncritical reading of the article may lead to the misguided conclusion that aggressive federal initiative is essential to meaningful K–12 change. So I’ll offer nine reasons to question the argument that reform had “stalled” prior to RTTT and that RTTT was the AAA truck that jumpstarted it.

First, some of today’s most important reforms came about prior to RTTT’s inception. Michelle Rhee began overhauling educator policies in 2007. Louisiana created the RSD in 2003 and used it to great effect in New Orleans in 2006–9. As Arne Duncan himself argues, Common Core was a pre-RTTT initiative. Charter schooling was underway in forty states prior to RTTT. States including New Jersey, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Maryland, Illinois, Missouri, and New York had taken over districts or schools prior to RTTT.

Second, the article offers no explanation for why policy reforms started growing in 2004 and began spiking in 2008 among future winners.

Third, RTTT funding was completely awarded by December 2011, meaning states no longer had any financial incentive to pass policies to Washington’s liking. But the analysis gives RTTT credit for reforms taking place in 2012–14. Much else could’ve exerted that influence, over that time, such as new state superintendents, a wave of new Republican governors and legislators, and ESEA waivers.

Fourth, the analysis treats never-applying states as a kind of control to show that RTTT influenced winners and applicants to implement reforms; it also mentions, however, that “adoption rates for all three groups increased dramatically.” The article explains this by giving RTTT credit for influencing never-applying states as well. But if all states were influenced by RTTT, we have no control group—meaning we can’t assess RTTT’s effect.

Fifth, if all states were affected by the RTTT intervention, we need a non-RTTT explanation for why states responded differently. It’s tautological to argue that winning states embraced more reforms because RTTT influenced them more.

Sixth, the article’s core argument is that RTTT financial incentives altered state behavior. But it doesn’t explain why some states were not affected (didn’t apply). This is important because the article then argues non-applying states enacted RTTT reforms to “keep pace” with applying states. But if the RTTT financial incentive was so significant and non-applying states did the hard work of passing reforms, why didn’t they just apply?

Seventh, the analysis establishes “control reforms” (like third-grade reading initiatives) that weren’t among RTTT priorities; the idea being that if RTTT had an independent influence, RTTT reforms would spike and control reforms wouldn’t. But winning states were likelier to pass at least one control reform. The article contends that that’s understandable because the controls were complementary to RTTT. But that means they weren’t really controls. This point is especially salient because during this era, states adopted many reforms unmentioned by RTTT. States passed dozens of private school choice programs. Indiana and Louisiana, which got no RTTT money, implemented leading accountability systems. Does RTTT get credit for those too?

Eighth, only one-third of interviewed state leaders said RTTT had a “massive” or “big” impact; 68 percent said it had a “minor” impact or none. Those in winning states were significantly likelier to credit RTTT with a large impact. But if the program had a predictable, independent influence, we wouldn’t see such variation. An equally reasonable conclusion—especially given the application’s reward for states’ previous activities—is that RTTT didn’t change behavior so much as reinforce existing behavior.

Ninth, the article concedes that RTTT had no influence on charter schooling, one of its priorities. If RTTT had a predictable, independent influence, this wouldn’t have occurred.

I raise these points not to nip at the heels of a very good researcher or diminish the legacy of this administration’s signature program. I want to better understand the influence of federal policy. I think RTTT was important; I’m trying to figure out how and why.

All nine of my objections share a single feature: They argue that things other than RTTT were at play in RTTT-era changes. I’m concerned that an undiscriminating “RTTT-is-responsible” interpretation will have four major downsides: reinforce progressives’ centralizing, technocratic impulses; obscure the differential influence the program had on various policies; distract us from the humbling responses to many RTTT policies (CCSS backlash, widespread rejection of the testing consortia, disappointing implementation results of educator evaluation systems); and discount the impressive state- and locally led reform momentum that preceded RTTT.

My next post considers these issues alongside the very different RTTT reflections of Rick Hess and Joanne Weiss.

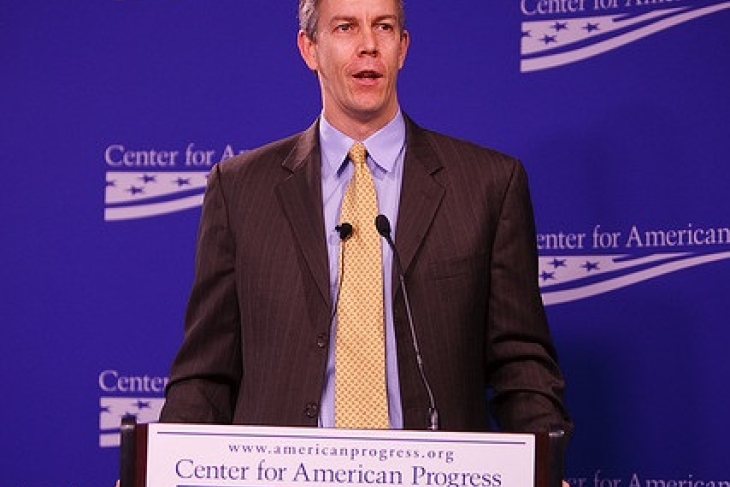

Center for American Progress/Flickr