In June 2023, Ohio policymakers established a statewide initiative that requires schools to follow the science of reading, an evidence-based instructional approach that focuses on phonics and knowledge-building. As part of this initiative, public schools (traditional district and charter) are required to adopt curricula and materials that appear on a state-approved list of high-quality options. Teachers are required to undergo professional development in evidence-based reading instruction, with stipends available for those who complete the training. Next year, the Ohio Department of Higher Education will begin auditing educator preparation programs to ensure teacher candidates are well-trained in the science of reading. And this year, eighty-four reading coaches are providing intensive support to educators in 115 schools and districts, up from thirty-three coaches in fifty-three schools last year.

This is a broad and bold effort. If implemented well, it could vastly improve reading outcomes. But it’s going to take time to see results. Ohio has hundreds of districts and charter schools and thousands of teachers. Many of them haven’t been using instructional methods aligned with the science of reading. What’s happening right now in Ohio schools is akin to turning around an aircraft carrier—it will take time and patience to change course, and there are no shortcuts. State policymakers need to resist the urge to repeat their troubling history of prematurely giving up on promising reform efforts.

But being patient doesn’t mean we shouldn’t keep a close eye on the data. The early literacy component on Ohio’s state report cards offers a detailed look at how districts and schools are faring in terms of reading progress. Because the current school year will be the first full year of implementation of the new Science of Reading reforms, the previous two academic years (2022–23 and 2023–24) should serve as the baseline for comparison going forward. And while statewide results matter, they can mask considerable growth (or lack thereof) at the district and school level. To get a true picture of Ohio’s early literacy progress, we need to dig into district-specific data.

In this piece, we’ll examine baseline early literacy results in the Ohio Eight, a group of eight urban districts with a long history of poor performance. Also included in the analysis are Lorain and East Cleveland, districts that spent several years under the oversight of now-defunct Academic Distress Commissions. (So did Youngstown, which is one of the Ohio Eight.) Together, these ten districts serve nearly 187,000 students—more than a tenth of the state’s public-school population—and are among those most in need of early literacy improvement.

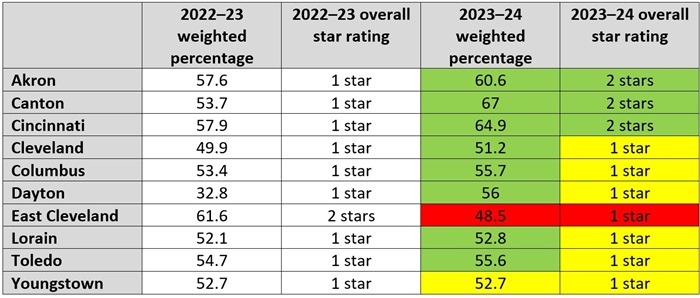

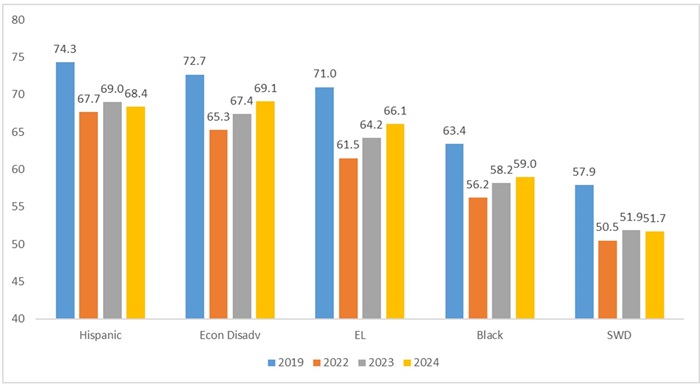

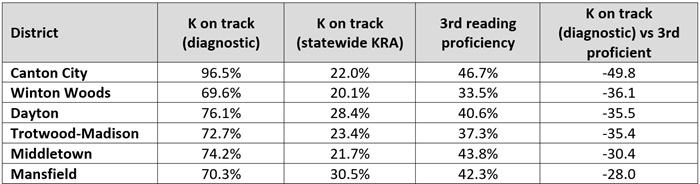

First, let’s look at how they performed overall on the early literacy component. Chart 1 below displays two data points—districts’ star ratings on the component and the weighted percentage that determined those ratings. This percentage is based on three measures: third-grade reading proficiency rates, third-to-fourth grade promotional rates, and the percentage of off-track readers who move to on-track status in the following year. Districts with a weighted component percent of 58 percent or below earned one star out of five and were identified as needing “significant support” to meet state standards. Districts with a weighted component percent from 58 to less than 68 percent earned two stars and were identified as needing “support.” In the columns for the most recent school year, green shading indicates improvement, yellow indicates results that remained flat, and red indicates a decline.

Chart 1. Overall early literacy results on state report cards

In 2023–24, eight of these ten districts earned higher weighted percentages than the year prior. Dayton, in particular, showed considerable improvement, as it jumped more than 23 percentage points. Unfortunately, the district’s 2022–23 weighted percentage was so low that even this significant improvement wasn’t enough to bump up its overall star rating. But three other districts—Akron, Canton, and Cincinnati—succeeded in improving from one star to two. East Cleveland, on the other hand, performed significantly worse. Not only did the district drop from two stars to one, its weighted percentage dropped 13 points.

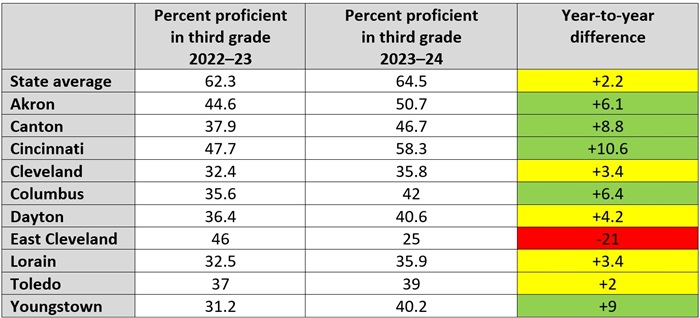

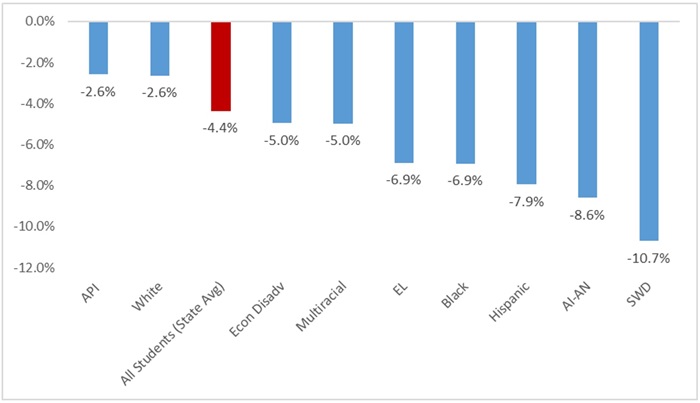

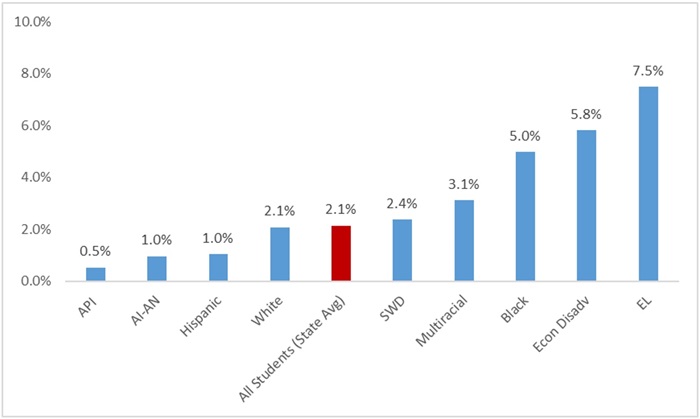

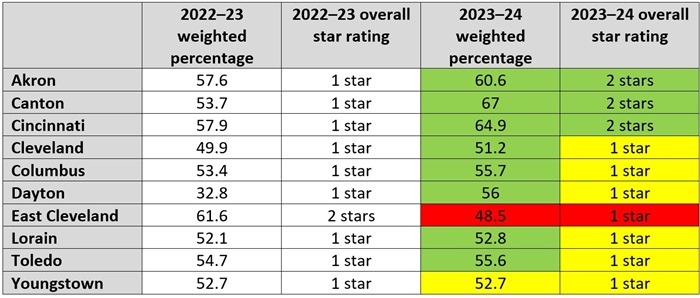

Next, let’s take a closer look at one of the early literacy component’s three measures: third grade reading proficiency. Research shows that reading proficiently by the end of third grade is an important benchmark for kids. That’s why Ohio policymakers assigned this particular measure the highest weight (40 percent) in the overall rating calculation for the component. Chart two displays the proficiency percentages of each district, as well as the statewide average and the year-to-year difference. In the final column, green shading indicates an improvement of more than five points, yellow indicates an improvement of less than five points, and red indicates a decline.

Chart 2. Percentage of third graders scoring proficient on the reading segment of state ELA exam

During the most recent school year, only two districts—Akron and Cincinnati—had more than half of their third graders reach proficiency. And in all ten districts, proficiency numbers are below the state average. However, eight of the districts had year-to-year improvement that outpaced the state (though the statewide average only improved by a modest 2 percentage points). Cincinnati performed the best, with a 10.6 percentage point jump that puts its overall proficiency rating just 6 percentage points shy of the state average. The worst performer was East Cleveland, which registered a massive 21 percentage point drop. Only a fourth of third graders in that district reached the state’s proficiency benchmark.

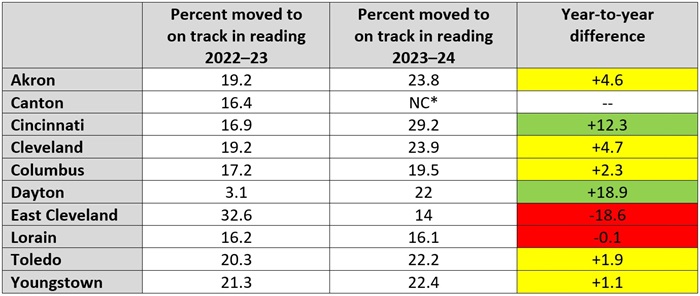

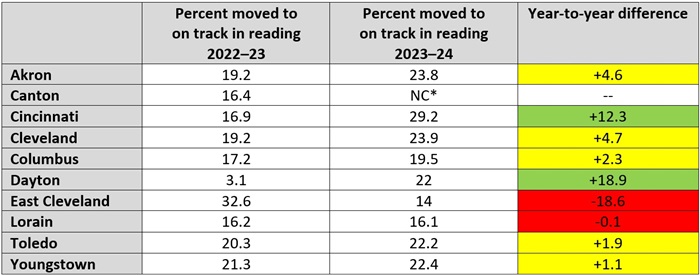

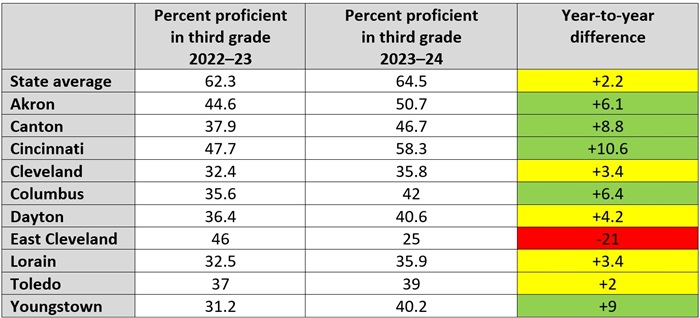

Proficiency isn’t the only component measure that deserves a closer look. It’s also important to identify progress, which the state does via the “improving K–3 literacy” measure. The Department of Education and Workforce (DEW) uses the results of fall diagnostic assessments to determine the percentage of students who move from “not on track” to “on track” in reading from one year to the next. These results indicate how well schools are improving K–3 literacy throughout all the early grades, not just third. By doing so, the measure identifies schools and districts that are making critical progress with struggling readers. Chart 3 displays the overall percentage of students that each district moved to on track in reading during the two most recent school years, as well as the year-to-year difference. In the final column, green shading indicates an improvement of more than five points, yellow indicates an improvement of less than five points, and red indicates a decline.

Chart 3. Results for the improving K–3 literacy measure on state report cards

*The improving K–3 literacy measure is NC, or not calculated, if more than 90 percent of kindergarten students are on-track.

*The improving K–3 literacy measure is NC, or not calculated, if more than 90 percent of kindergarten students are on-track.The good news is that most districts did much better in 2023–24 than the year prior. Dayton is the big winner, as it registered an increase of nearly 19 percentage points. Cincinnati also did well with an increase of 12 percentage points. However, even with these improvements, not a single district succeeded in moving more than a third of its off-track students to on-track. In fact, some are doing an extremely poor job. Lorain’s 0.1 percentage point drop might not seem like a big deal, but the district moved only 16 percent of its off-track readers to on track. In that context, any decrease—no matter how small—is terrible news. Meanwhile, East Cleveland continued its run of sharp declines, registering a drop of more than 18 percentage points. In just one year, East Cleveland went from being the highest performer on this list to being the worst.

***

Ohio is on the cusp on something big with early literacy. If policymakers can be patient and stick with it, Ohio could see significant improvement in reading outcomes. Nowhere is that improvement more necessary than in the Ohio Eight and the districts previously run by Academic Distress Commissions. Judging by the data outlined above, these districts have a long way to go. But thanks to the science of reading and Ohio’s recent reform efforts, that mountain should be a little easier to climb.