Author update (10/11/24): Since this piece was posted, sources have indicated Canton’s kindergarten data were misstated on its report card—a possibility acknowledged in this piece. The district's report card, as well as its elementary school report cards, now have “watermarks” flagging the data reporting error and indicating that the error may have impacted the ratings. One of the policy issues raised in this piece—that schools could implement weaker assessments to avoid accountability—remains a significant concern. However, it does not appear that Canton has done this. The original text of this piece remains unchanged, but the title has been revised (it was originally titled “Canton’s early literacy data raise questions about kindergarten assessment”).

Last week, my colleague Jessica Poiner published a terrific analysis about the early literacy results from the 2023–24 school report cards. The entire piece is worth a read. Yet one striking data point deserves additional attention, as it suggests inconsistencies in the way districts assess and report kindergarten students’ literacy skills. The result of these inconsistencies could be preventing children with reading deficiencies from accessing the supports they need to become strong readers.

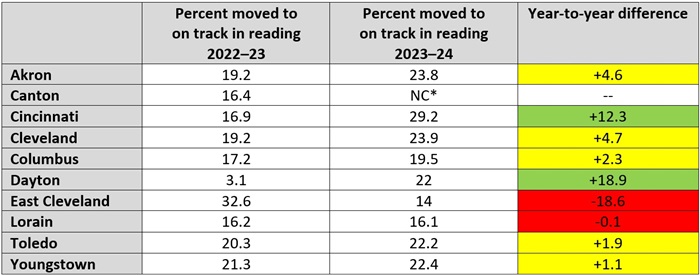

The table below is from Jessica’s analysis and shows some districts’ year-to-year improvement rate among students in grades K–3 who are struggling in reading. All of these high-poverty, urban districts reported data on this measure—except for Canton City Schools. The note at the bottom of the table explains the omission, referring to a provision (loophole, if you will) in state law that exempts districts and schools from this measure when more than 90 percent of kindergarteners are on track based on a fall diagnostic literacy assessment.

Table 1. Results for the improving K–3 literacy measure on state report cards

Given research finding significant early childhood language gaps by socioeconomic status and the large number of economically disadvantaged students that Canton serves, it’s shocking to see that the district was exempt. But it’s true: Canton’s early literacy data reveal a whopping 97 percent of kindergartners were on track last fall, thus allowing the district to be exempt from the improvement measure. In contrast, a more realistic 53 and 49 percent of Cleveland and Columbus kindergarten students were identified as on track.

Canton is a notable outlier among the eighty-three districts that were exempt in 2023–24. It is the only urban district to receive an exemption out of fifty-five such districts statewide (including the ten listed above plus several other inner-ring suburban and small-city districts). The district is also one of just twelve exempt districts that posted a third-grade reading proficiency rate of less than 70 percent. In fact, Canton’s 47 percent proficiency rate was the third lowest of the exempt districts and thirty-first lowest among Ohio’s 605 districts.

We don’t know what exactly is behind the district’s unexpectedly high on-track rate. One possibility is a reporting error. While there is no “watermark” in the data file signifying concerns from the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce about Canton’s literacy numbers, this possibility certainly warrants further exploration. If this is the case, the error would have occurred not only at the district level, but also in Canton’s nine elementary schools, which all reported kindergarten on-track rates of 90 percent or above.

Another explanation is that Canton actually had 97 percent of entering kindergartners legitimately on track in literacy. If true, this would be an incredible feat on the part of the city’s parents, caregivers, and preschools that should be cause for celebration. Yet in 2022–23, Canton reported just 21 percent of its kindergarten class was on track in reading, and as noted above, the district’s 2023–24 data are quite the outlier. The near-universal identification of on-track kindergartners also deviates from Canton’s language and literacy results on the statewide Kindergarten Readiness Assessment—but whose results the district chose not to use for the purpose of on and off track identification.[1] On that assessment, just 22 percent of Canton kindergarteners were deemed on track.

A more troubling possibility is that Canton is exploiting the kindergarten diagnostic assessment, perhaps in a misguided effort to avoid accountability for improving students’ reading skills. Recall that districts are permitted to select among more than a dozen state-approved assessments. Canton’s sky-high on-track rate calls into question which one it used—unfortunately, that’s not reported in state datasets—and whether the district has recently discovered a test that is more apt to identify students as being on track (or an assessment with a low “cut score”).

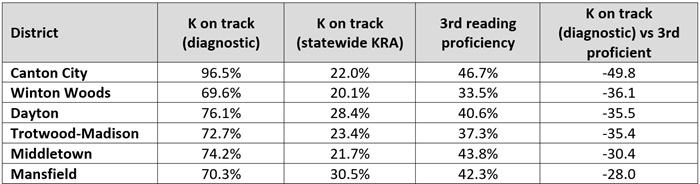

If the assessment-based explanation holds, Canton wouldn’t be the only district that may have identified a diagnostic that provides an overly rosy picture of children’s literacy skills. As the table below illustrates, several other districts with low third grade reading proficiency rates identify large majorities of kindergartners as on track. While not quite reaching the 90 percent exemption threshold, Dayton Public Schools identified 76 percent of its kindergartners as on track even though just 41 percent of its third graders achieved reading proficiency in 2023–24. To be sure, a lot happens between kindergarten and third grade, and these are different student cohorts. But discrepancies of this magnitude raise questions about some districts’ choice in diagnostic assessment. These types of disparities are evident in the prior year’s data too and—as displayed in the table below—when comparing districts’ on-track rates on a self-selected diagnostic versus those based on the statewide Kindergarten Readiness Assessment, both of which were given to the same cohort of students in the fall of 2023.

Table 2: Districts with large discrepancies in kindergarten on-track rates (fall) and third grade reading proficiency rates, 2023–24

This is all more than just a data-quality concern. These results also have implications for how schools serve children struggling to read.

First, as the case of Canton illustrates, districts and schools can duck report-card driven accountability for improving struggling students’ literacy skills based on results from the fall kindergarten assessment. This eases the pressure on schools and could weaken their efforts to improve literacy among children who need extra help. Canton’s free pass on the improvement measure may have also inflated its Early Literacy report card rating, leaving parents and the community with a false sense of progress. The district received two stars on this component last year, a notch above its one-star rating in 2021–22 when improvement was included.

Second, children erroneously deemed “on track” are unlikely to receive extra supports even though they have significant need for intervention. Under Ohio’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee, schools must implement—with parental involvement—a reading improvement and monitoring plan for children in grades K–3 who are off track. Students who are identified as on track (including the hundreds of kindergartners in Canton last year) are not entitled to such supports.[2]

An honest assessment of children’s language and literacy skills is the first step in helping them become proficient readers. The most recent data from Canton and several other districts raise questions about how some schools identify children with reading deficiencies. State policymakers should make sure districts implement assessments that provide accurate information about literacy skills, so that all children receive the support they need to become good readers.

[1] Districts are permitted to select among more than a dozen state-approved kindergarten literacy assessments to identify on- and off-track students in grades K–3. Currently, schools may select from fifteen state-approved diagnostic reading tests, or (for kindergarten) use results from the language and literacy portion of the state-required Kindergarten Readiness Assessment.

[2] Misidentification of off-track readers could also happen based on results from the grades 1–3 fall diagnostic assessments.