One of the most pressing challenges facing American education is closing achievement gaps. Beginning with the Coleman Report released in 1966, analysts have documented large disparities in academic outcomes based on students’ backgrounds. Depending on how the gap is measured—whether by socioeconomic status or race/ethnicity and along which assessments—researchers today estimate that less-advantaged pupils are on average anywhere from three to five grade levels behind their peers.

While there are pockets of success—particularly among exceptional public charter schools—U.S. schools overall have a disappointing track record in addressing the achievement gap. In a 2020 paper, Stanford University’s Eric Hanushek and colleagues find that, although gaps by students’ socioeconomic status (specifically based on parental education and at-home resources) have slightly narrowed over the past four decades, they are not closing at a fast enough pace. They conclude that, at this rate, “it would take another century and a half to completely close the gap.”

We must do better. Students from disadvantaged backgrounds need the same level of knowledge and skills as their counterparts to succeed after high school. That’s why political leaders in both parties—including presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama—have called closing achievement gaps the civil rights issue of our time.

Unfortunately, the pandemic widened these gaps and reversed much of the progress that had been made. Ohio and other states have their work cut out to accelerate learning and ensure that all students achieve at high levels. This piece examines where Ohio stands in terms of achievement gaps on state exams and whether any post-pandemic progress is being made. The focus is on the state’s performance index scores, a composite measure of achievement on all state exams that weights higher test scores more heavily. This measure provides a broader picture of achievement on state tests than proficiency rates, which focus more narrowly on clearing the proficiency bar. Results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) provide further perspective on Ohio’s achievement gaps—versus national and over longer timespans—and we’ll look at those when the latest data are released in early 2025.

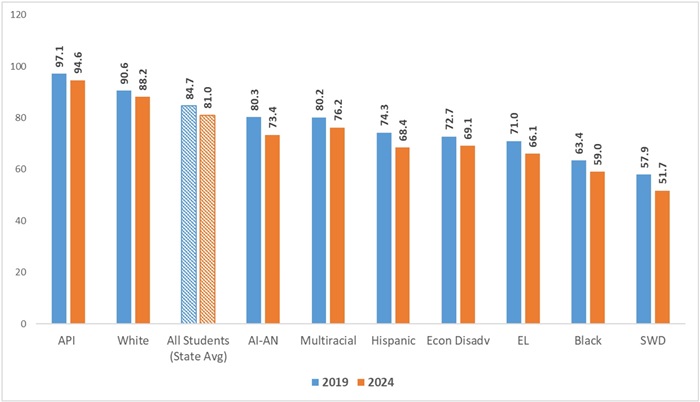

Figure 1 displays performance index scores by the various student groups delineated in federal law. As indicated by the blue columns, pre-pandemic (2018–19) achievement gaps are clearly evident. The scores of Black and Hispanic students, economically disadvantaged students, English learners, and students with disabilities fell well below those of Asian/Pacific Islander and White students, as well as the statewide average (all students). The orange columns represent the most recent scores from 2023–24, and show persistently wide achievement gaps.

Figure 1: Performance index scores by subgroup, 2018–19 to 2023–24

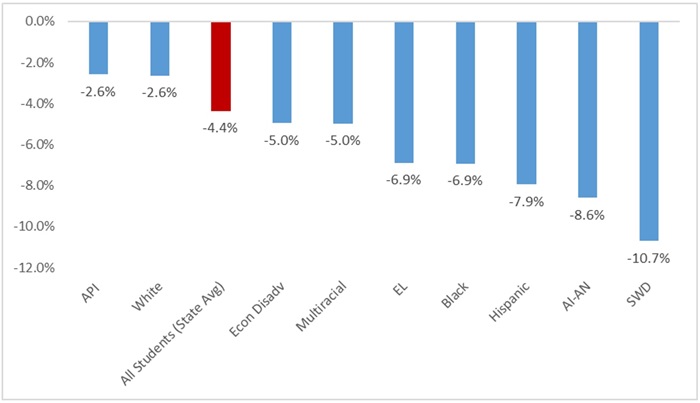

Compared to the 2018–19 pre-pandemic baseline, achievement gaps have grown. As indicated by the figure below, American Indian or Alaskan Native,[1] Black, and Hispanic students, as well as students with disabilities, have suffered larger test-score declines. The performance index scores of Black students, for instance, are 6.9 percent lower in 2023–24 than in 2018–19, whereas the White student loss is 2.6 percent. The larger decline in Black scores has thus widened the Black-White achievement gap relative to the pre-pandemic baseline.

Figure 2: Percent change in performance index scores, 2018–19 (pre-pandemic) to 2023–24

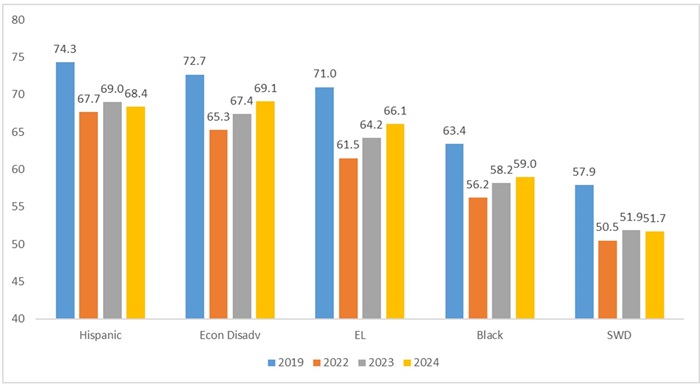

Turning to a focus on post-pandemic trends, we begin to see some hopeful signs. Figure 3 below zeros in on the results of the lower-achieving student groups. Here, we observe steady post-pandemic improvements among economically disadvantaged students,[2] English learners, and Black students relative to their 2021–22 baselines (orange columns). Less improvement, however, is visible among Hispanic students and students with disabilities.

Figure 3: Performance index scores by at-risk subgroup, 2018–19 to 2023–24

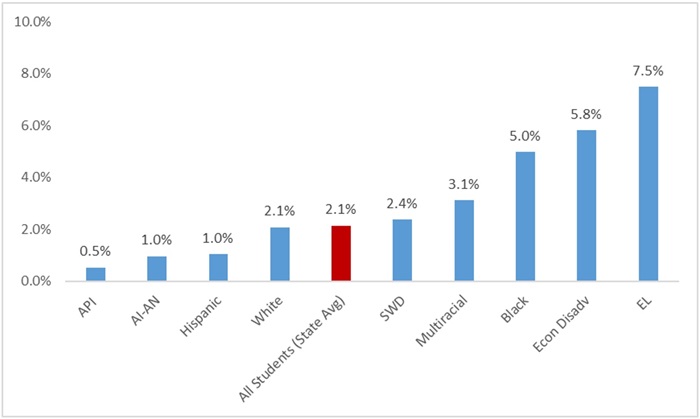

The faster post-pandemic progress of Black, economically disadvantaged, and English learner student groups is more apparent when we look at the improvement in scores from 2021–22 to 2023–24. Scores for English learners rose the fastest during this period—up 7.5 percent—with economically disadvantaged and Black students close behind (+5.8 and 5.0 percent, respectively). These rates of improvement exceed those of their more advantaged peers and the statewide average. Thus, achievement gaps for these groups have somewhat narrowed after the widening that occurred during the pandemic.

Figure 4: Percent change in performance index scores, 2021–22 (post-pandemic) to 2023–24

* * *

The 2023–24 data present a mix of good and bad news. First and foremost, they remind us of the urgent need to significantly raise the achievement of Ohio’s most vulnerable student groups. For Ohio leaders, there remains a clear moral imperative to work towards ensuring that all students can read, write, and do math proficiently.

Yet there are also signs of progress. The faster post-pandemic improvements in the scores of economically disadvantaged and Black students is notable and may reflect the impact of federal Covid relief funding, much of which was directed to high-need, urban districts. (Vlad Kogan’s recent analysis suggests that these dollars slightly boosted math achievement after the massive pandemic setbacks.) It might also reflect the steadily improving—and, as of late, better funded—urban charter schools that serve primarily disadvantaged students. It may even be an early sign that Ohio’s renewed focus on early literacy is already yielding some academic gains (and note that third grade reading proficiency was up in all of the Ohio Eight urban districts).

Of course, more still must be done to keep the needle moving in the right direction. Federal Covid relief aid will soon dry up, and state legislators will need to seek creative ways that enable schools to prioritize academics, preserve effective programs, and retain high-performing teachers. Chronic absenteeism remains far too high—especially in Ohio’s urban communities—and state and local leaders need to push harder for regular school attendance. Finally, state policymakers must continue to hold schools accountable for academic results—and they need to press for changes when schools continually fall short of performance goals.

Exceptionally-high-performing schools have proven that achievement gaps can be overcome. But closing the gap at a system-wide level has proven elusive. It will take a relentless focus on strong academics to ensure that all Ohio students, no matter their background, acquire the skills they need for success in life.

[1] This student group comprises just 0.1 percent of Ohio students in 2023–24.

[2] Some of the improvement in the economically disadvantaged subgroup could reflect an increasing number of non-disadvantaged students being identified as “economically disadvantaged” due to blanket identification when schools participate in the Community Eligibility Provision.