A closer look at Ohio’s industry-recognized credential data

Since taking office in 2019, Governor DeWine has prioritized expanding and improving

Since taking office in 2019, Governor DeWine has prioritized expanding and improving

Since taking office in 2019, Governor DeWine has prioritized expanding and improving career pathways. One of the benefits of a well-designed pathway is the opportunity for students to earn industry-recognized credentials (IRCs). Credentials allow students to demonstrate their knowledge and skill mastery, verify their qualifications and competence via a third-party, and signal to employers that they are well-prepared. IRCs may be prerequisites for certain jobs and can also boost earnings and employment.

Although Ohio has some room to grow when it comes to data collection and transparency, it does annually track IRCs at the state and district level. In this piece, we’ll examine a few takeaways from the most recent state report card.

1. The number of credentials earned by Ohio students is skyrocketing.

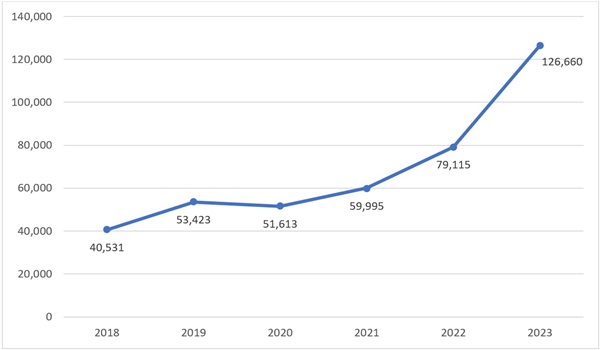

Over the last few years, the number of credentials earned has dramatically increased. Chart 1 demonstrates that between 2018 and 2023 the number tripled. The two most recent years, 2022 and 2023, represent a particularly steep incline.

Chart 1. Number of credentials earned statewide, 2018–2023

This credentialing surge can be attributed to several factors. First, state-funded initiatives like the Innovative Workforce Incentive Program—which was designed to increase the number of students who earn qualifying credentials in “priority” industry sectors—are likely having an impact. Second, Ohio lawmakers passed a revised set of graduation requirements in 2019 that made room for career pathways. Under these standards, students must not only complete course requirements to earn a diploma, but also demonstrate both competency and readiness. For the competency portion, they are permitted to meet standards based on career experience and technical skill, which can include earning at least twelve points in the state’s credentialing system (more on that below). For the readiness portion, students must earn at least two diploma seals. The Industry-Recognized Credential Seal is one of those options.

2. It’s unclear whether the most-earned credentials are valuable to students.

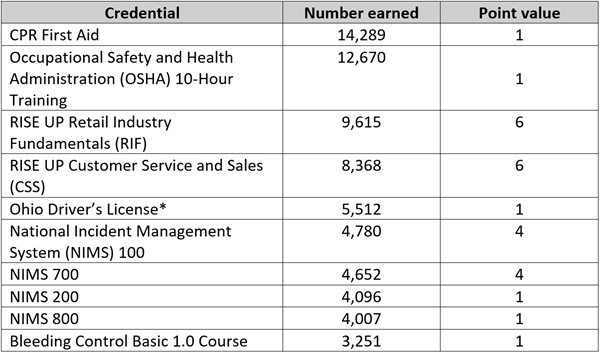

There are several ways to determine the value of a credential. One is by considering whether the state has identified it as valuable. In Ohio, credentials are assigned a point value between one and twelve. Point values are based on employer demand and/or state regulations and often signal the significance of the credential. For example, within the health career field, credentials like CPR First Aid or respiratory protection are each worth one point. In that same career field, a Certified Pharmacy Technician is worth twelve points. Unfortunately, as demonstrated by Table 1, none of top ten credentials earned by students in Ohio are worth twelve points. Half are worth just one point.

Table 1. Top ten credentials earned statewide 2023

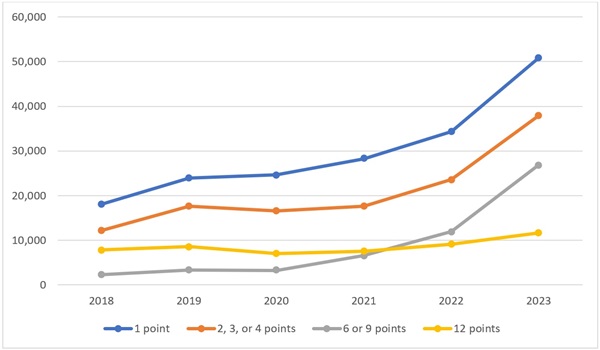

The prevalence of one-point credentials isn’t a recent development. Chart 2 demonstrates that credentials worth one point have consistently been the most earned since 2018. Over the last six years, the number of twelve-point IRCs being earned hasn’t increased as rapidly as the number of one-point IRCs earned. And the gap between the two has grown each year. In 2018, the gap between one-point and twelve-point credentials was just over 10,000. By 2023, it had grown to more than 39,000.

Chart 2. Credentials earned statewide according to point value, 2018–2023

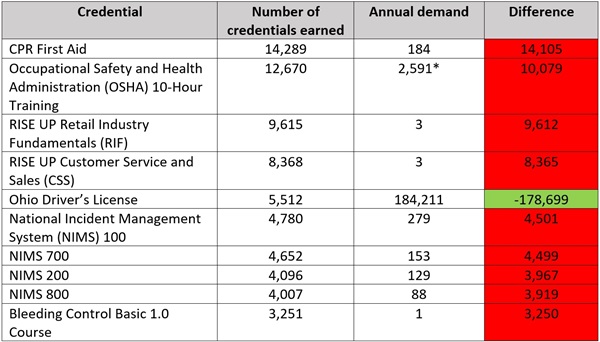

Another way to determine value is by examining employer demand. If employers are eager to hire graduates who possess a certain credential, then that credential is more valuable. But determining demand can be difficult, as employers often don’t signal which credentials are necessary for a job position, which are just “nice to have,” and which are irrelevant. A 2022 analysis of IRCs conducted by ExcelinEd and Lightcast attempted to offer some insight on employer demand by examining the average annual number of Ohio job postings that requested credentials over a two-year period (2020 and 2021). It’s by no means a perfect measure—it’s possible that employers value certain credentials even if they don’t mention them in job postings, and that some IRCs give students an unseen boost over other applicants. But until Ohio has better data, job postings are the easiest way to uniformly assess employer demand across the state.

Table 2 below identifies the top ten credentials statewide and how many were earned in 2023. Column three identifies the average annual number of Ohio job postings that requested each credential. Column four calculates the difference between recent supply (the number of credentials earned by the class of 2023) and previous employer demand. Red shading indicates that a credential is oversupplied, while green shading indicates an undersupply. With one exception—a state-issued driver’s license—all of Ohio’s most frequently earned credentials were not in high demand by employers. That should concern us.

Table 2. Annual demand for top ten credentials earned statewide

A third way to consider value is through wages and salaries. Unfortunately, as is the case with employer demand, wages and salaries can be difficult to pin down. The aforementioned IRC report offers some insight. For example, although National Incident Management System (NIMS) credentials don’t have much annual demand, the postings that do request them have advertised wages above $50,000. But other credentials in Ohio’s top ten list—like CPR First Aid, OSHA 10-Hour, and RISE UP Retail Industry Fundamentals—don’t have advertised wages identified by the report. In other words, we don’t know for sure that students who earn these credentials end up in well-paying jobs. Going forward, it will be crucial for state leaders to follow through on linking education and credentials with workforce outcomes like wages.

3. Some districts are posting higher credential numbers than others.

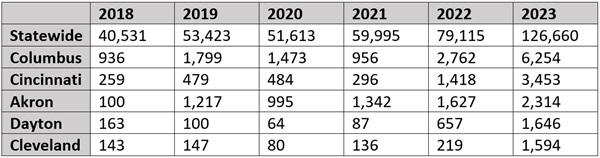

In 2023, the five districts with the highest number of IRCs were Columbus, Cincinnati, Akron, Dayton, and Cleveland. All five of these districts are in the Ohio Eight. Together, they account for nearly 9 percent of Ohio’s students and roughly 12 percent of the credentials earned statewide. Table 3 identifies credential earning numbers from the last six years for each district as well as the state.

Table 3. Number of credentials earned in selected districts, 2018-2023

Given that it’s the largest district in the state, it’s not surprising that Columbus posted the highest number. In fact, in 2023, the district made up nearly 5 percent of all credentials earned statewide. But there have been some pretty significant increases elsewhere, too. Akron, for instance, went from 100 credentials earned in 2018 to more than 1,200 the following year. Other districts, like Cincinnati, Dayton, and Cleveland, didn’t see sharp increases until 2022 or 2023.

These rapidly rising numbers raise some important questions. For example, what credentials did students start earning in Akron to account for such massive growth? Are Columbus students earning the same credentials in 2023 that they were in 2018? To find out, we compiled some additional tables that can be found here. They identify the top three credentials earned in each district between 2018 and 2023. The number of IRCs earned appears in parentheses. There are a few interesting data points to note.

First, Akron’s sudden surge is attributable to RISE UP credentials. Since 2019, students in the district have earned 2,529 Retail Industry Fundamentals credentials and 1,739 Customer Service and Sales credentials. Each of these IRCs is worth six points and can be earned in the same career field (business, marketing, and finance or hospitality and tourism), which means students can bundle them to earn a diploma. And yet, according to job posting data, neither credential is in demand by employers. Remember, it’s still possible that employers in the Akron area value these credentials. But we don’t know for sure. In a similar vein, we have no idea whether these credentials lead to well-paying jobs with advancement opportunities. Until Ohio directly links workforce outcome data to credentials, there’s no way to know whether Akron students who earned these IRCs are better off.

Second, Cleveland’s sudden increase between 2022 and 2023 is also attributable to RISE UP credentials. The district’s top credential during 2022 was Microsoft Office Specialist PowerPoint 2016, with twenty-one credentials earned. The following year, the top credential was Retail Industry Fundamentals (223 earned), followed closely by Customer Service and Sales (217 earned).

Third, in the last two years, an increasing number of Columbus students are earning credentials from the National Incident Management System. These IRCs account for the district’s top four credentials in 2023, adding up to a total of 2,913. That’s approximately 46 percent of the district’s 2023 total. Columbus isn’t the only district that’s championing these credentials, either. Cincinnati and Cleveland also had National Incident Management System credentials in their top three during 2022 and 2023.

***

Over the last few years, Ohio policymakers have prioritized improving career pathways. Expanding opportunities to earn an IRC has been a key part of those efforts. The good news is that more students than ever are earning credentials. The bad news is that it’s unclear whether the students who are earning those credentials are better off. Going forward, Ohio leaders must carefully consider how to ensure that students—and schools—are incentivized to focus on meaningful credentials that lead to well-paying jobs.

At Partnership Schools, we are excited that so many Ohioans are excited about the “science of reading.” In 2023 legislation that took effect this school year, Governor DeWine and the General Assembly have mandated that all reading curricula follow this approach—one we know well, since Partnership Schools have implemented it for over a decade.

The science of reading is a body of research that points to several key ingredients for effective reading instruction, particularly systematic phonics instruction and building background knowledge, of which vocabulary is perhaps the most important form. Veteran Cleveland Partnership teacher Lisa Marynowski and members of our academic team explained those elements in a Partnership Post back when the legislation passed.

But as the Fordham Institute’s Aaron Churchill astutely points out in a comprehensive road-map to effective rollout of the policy, curriculum mandates won’t advance students’ reading without effective implementation. Aaron notes that twelve of fifty-five urban districts in Ohio were already using strong science of reading curricula before the mandate went into effect, including the curriculum our schools use: Core Knowledge Language Arts.

The right materials and sequencing are essential. Yet as Aaron notes, teachers and schools must use these tools effectively to help students read well.

Since the Partnership network of schools began over a decade ago, we’ve been working to level up our implementation of curricula based on the science of reading. We are still learning how best to support teachers as they undertake the incredibly complex, vital work of teaching young people to read fluently, with deep understanding and engagement in the texts they are reading.

So what have we learned so far about effectively implementing research-backed reading curricula in our classrooms?

1. Even best-in-class curricula—based on the science of reading—don’t teach students to read. Teachers do.

We see a real difference in students’ progress depending on how teachers implement the curricula. When a teacher implements the curriculum with fidelity—holding a high bar both for their lesson preparation and the learning they expect students to demonstrate—then young readers learn avidly and are hungry for more. But when teachers implement a curriculum out of compliance alone and without a spirit of curiosity and rigor, students progress far more slowly.

2. Most elementary educators are not trained to teach phonics, so we owe them effective, efficient training to develop that skill. But to build the skill, we also have to—and can—build the will.

Anyone who thinks teaching phonics is simple can get a taste of how complex it is from this analysis of just two minutes of effective phonics practice from Teach Like a Champion’s Doug Lemov and Jen Rugani.

Jen has a growing fan base among our teachers in Cleveland, whom she has trained. She packs a lot into a day’s workshop. But even when the list of skills to teach and practice is long, she takes the time to start with cognitive science and reading research. Teacher buy-in increases as they reflect on how that science shows up in their own experiences as readers. As a result, Jen builds teachers’ will to implement curricula effectively by exploring the why behind the work with them first. We find that when teachers are more familiar with the research behind what they’re doing, their will to do it well often increases.

3. Teaching phonics well requires a high degree of precision, expert modeling, and real-time feedback to students.

In baseball, the difference between a home run and a foul ball is often a matter of millimeters—a shoulder just a smidge too high or weight distribution that’s just a little off. The same is true of teaching phonics well: The little things matter a lot.

For a deeper dive into the fine points of what we see great early elementary reading teachers doing, an overview of how a few of our colleagues adapted to do it during Covid still resonates with us.

4. The work doesn’t end at third grade.

The complex texts students should encounter as they get older will challenge the limits of their fluency. Sometimes described as “meaning made audible,” fluency spans the ability to read with automaticity, appropriate intonation, and expressiveness. It is the job of teachers at every level to build fluency through instruction, in both explicit and implicit ways. They can do that in part with lots of shared reading aloud, in which teachers carefully prepare to maximize fluency development and comprehension at the same time.

Note that we say students should encounter complex texts. Too many students don’t read rigorous, grade-level texts as they get older, and that is deeply problematic for their success in high school and beyond. For so many reasons, it is crucial for us to center ambitious books in our reading classes, as Doug Lemov and Emily Badillo, another expert who has trained our upper elementary and middle school teachers in cultivating fluency, elaborated in Education Next recently.

5. Urgency matters.

We must teach every day like the future of our students hangs on the next few minutes of instruction—because it does.

That urgency calls on us to do many things well—including lesson pacing. Our team has developed year-long pacing guides that go beyond slotting in one lesson a day, and we try to guide our teachers in how to judge when some skills may need an extra day of instruction.

—

These are not easy decisions with high-quality reading materials, though. These curricula are dense, involve spiraled practice and repetition over time, and students come to us with varying degrees of readiness for the work. Yet their cumulative growth depends on teachers teaching deeply the entire scope and sequence by the end of the year, one year after another.

A few years back, our colleague Fiona Palladino coined the phrase “patient urgency” to describe how we needed to make progress as educators. It is an ethos that Ohio legislators, educational pundits, and parents might adopt now, as we all seek to improve students’ reading. Like all deep investments in children’s learning, the shift to implementing curricula based on the science of reading must be done well and urgently—and it will require years of sustained resolve, knowledge-building, and responsive implementation to produce the gains we seek.

But in our experience—one in which we get to go into middle school classrooms and hear students reading complex texts like The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass fluently or gasping out loud at details in the works of John Steinbeck and C.S. Lewis—that effort is worth every minute.

Fordham recently published results from a parent survey on educational opportunity in Ohio. Produced in partnership with 50CAN and Edge Research, the nationwide survey collected feedback from more than 20,000 parents and guardians of school-aged children in all fifty states and the District of Columbia. In Ohio, the survey was completed by 408 parents. Here’s an overview of three significant takeaways from the Ohio-specific results.

1. Ohio parents have access to school choice and like it.

Over the last few decades, Ohio policymakers have consistently expanded school choice options for families. The most recent state budget, for example, broadened voucher eligibility, increased funding for charter schools, and improved transportation guidelines (though recent events prove there’s still plenty of work to do on that front). According to survey results, those efforts have paid off. On average, 68 percent of parents feel like they have a choice in what school their child attends, slightly higher than the national average of 65 percent. More than two-thirds (67 percent) say they would make the same choice again. It’s telling that the vast majority of Ohio parents say that they feel like they have a choice and would make the same choice again.

Even better, a whopping 71 percent of low-income parents in Ohio reported feeling like they have a choice compared to 61 percent nationally. Historically, economically disadvantaged families have the least amount of choice. That’s because high-performing districts require residency for enrollment, and real estate prices are typically beyond the financial reach of many families. Private school tuition is also steep. But in Ohio, options like charter schools (which posted stronger academic growth numbers than their district counterparts this year), private school scholarship programs, and open enrollment provide low-income families in all communities—urban, suburban, and rural—with more choices than they would have otherwise. Families can, and often do, choose to enroll their children in their assigned traditional public school. But Ohio parents saying they feel like they have options matters because choice shouldn’t be limited by income.

2. Few parents seem to be consuming Ohio’s information on schools.

Each year, Ohio’s school report cards offer families, stakeholders, and policymakers a wide variety of data about school performance and student outcomes. Unfortunately, survey results indicate that many Ohio parents may not realize they have a treasure trove of data at their fingertips. On average, only 28 percent said they reviewed information about their school’s performance compared to other schools. That matches the national average, but twenty-four states registered higher percentages. Even worse, there’s an alarming gap between families of different income levels. More than a third (34 percent) of middle- and high-income parents reported that they reviewed school performance data. But less than a fifth (18 percent) of low-income parents did so. That means low-income families are viewing school performance data at roughly half the rate of higher-income families.

It’s unclear what’s causing this gap. It could be that families are not aware of school report cards, let alone choosing to use them to compare school performance. But it’s also possible that they feel Ohio’s system is difficult to navigate or that online report cards aren’t as user-friendly as they could be. Either way, state and local leaders need to do a better job of communicating with parents, especially those in low-income communities.

3. Most Ohio parents don’t believe their children are ready for the next step.

Ensuring that students are ready for what comes after graduation is a top priority for families and one of the chief responsibilities of schools. But survey results show that Ohio parents have some concerns. Only 39 percent are “extremely confident” that their child will be well equipped to succeed in the workforce, and only 36 percent feel that way about college preparation. On the one hand, both numbers are higher than the national average, which is 34 percent for workforce preparation and 32 percent for college. That means Ohio fell into the top tier among other states. But on the other hand, only a third of Ohio parents believe that their kids are ready for the next step, whether it's work or higher education. That’s worrisome.

***

Results from parent surveys like this are incredibly useful for policymakers. They pinpoint areas where policies and programs have been successful, like school choice expansion. They also identify areas for growth, like ensuring parents are aware of school performance data and prioritizing initiatives aimed at improving student readiness. Here’s hoping Ohio leaders pay close attention to these results as they head into budget season.

The term “citizen science” refers to research in any field conducted with participation from the general public and/or amateur researchers—a way of crowd-sourcing data in more volume through observations or experiments conducted outside of a lab. Citizen science (CS) is utilized by NASA, NOAA, and other reputable research entities and was front and center during the solar eclipse earlier this year. CS also has the potential to allow K–12 students access to a broader range of scientific education than a typical classroom can offer, including data analysis and reporting. A new report looks at how two teachers have attempted to implement CS at the elementary level. It’s a limited picture, but this qualitative report does go inside the black box of the classroom, giving us some curricular ins and outs that are illuminating.

A group of researchers led by Sarah J. Carrier of North Carolina State University are engaged in a multi-year study of CS in elementary classrooms. Specifically, the development, deployment, and evaluation of curriculum support materials to help a group of teacher volunteers integrate two CS projects—one conducted by the National Weather Service, the other by a national nonprofit organization—into their classrooms. The new report is a case study of two fifth grade teachers implementing these materials in year three of the larger study. These were chosen for analysis because the CS project content aligned with the fifth grade science standards (weather and ecosystems) in the unnamed state(s) where the schools were located. They also connect science to other subjects such as English language arts (reading and writing informational text), math (manipulating data and graphing), and social studies (mapping). The primary questions: How do teachers incorporate CS projects in their classroom and in the schoolyard and how do teachers navigate their school contexts to include CS projects in their science instruction?

Both teachers were twenty-year veterans at Title I schools (meaning they had a high percentage of their students identified as economically disadvantaged). The schools posted years of low performance ratings in math, reading, and science, the last of which fell far below their state’s average regularly. The schools were located in rural communities in unidentified state(s) in the southeastern part of the country. Both teachers received one day of professional development training on the CS projects, as well as the researchers’ curricular materials. While these data come from year three of the larger study, it is important to note it was year one for actual classroom deployment. Data come from teacher-provided documentation of their use of the materials, along with data from classroom observations, instructional logs, teacher interviews, and student focus groups. No dates of implementation are provided.

One teacher, called “Taylor,” reported both internal and external barriers to full implementation of the curricular materials. As a result, her students had very limited exposure to CS. Barriers included skepticism about students’ abilities to understand and execute the more concrete scientific and mathematical operations required and her belief that “administrative pressure to prepare students for science assessments” meant that science activities not directly related to concepts and tested vocabulary took precedence over everything else during class time. Most lessons consisted of vocabulary review and test preparation, along with video clips and lectures. Taylor’s students did not participate in data analysis or share CS data with the science community. In fact, the totality of data from the research team suggested that her students went into the schoolyard to search for ladybugs—a single aspect of just one of the CS projects—for only eight minutes on a single day when an observer from the team was present.

The other teacher, called “Morgan,” reported similar concerns about her students’ abilities related to the CS projects. However, she told the researchers that “Just because they are low in math and reading does not mean they cannot do science. It just means that I’ve got to adjust.” Observation and interview data showed Morgan devoting significant time to reviewing both the curricular materials and the two CS projects themselves. In a mid-year interview, she reported that she had adapted the materials to her students’ abilities and interests. In the end, she documented student activity with the CS projects (checking a rain gauge, entering data, or doing class activities) during thirty-one weeks of the year. She reported needing to bolster her students’ knowledge of geography and topology and re-teaching how to set up and label a graph (all of which, she states, should have been learned in fourth grade). Morgan also taught her students how to enter rainfall data into a spreadsheet and upload it to the National Weather Service website. Most students ended the year able to do this work independently. In a focus group, one of Morgan’s students confirmed that reading a rain gauge all year helped them to learn about “the decimals to where we understand how much it is.” Another student reported, “We measure the precipitation by hundredths.”

Carrier and her team conclude that the commonalities of Morgan and Taylor’s student populations, school contexts, and CS curriculum supports demonstrate the importance of teachers in science education (at least in this limited context). They also believe they can refine their curriculum support materials to help various types of teachers. Taylor’s teaching style is described as “teacher-focused” and she herself as a “selective user” of curriculum, with many external influences limiting her ability to plan, adapt, and deploy curricular materials. Morgan’s teaching style, on the other hand, is described as “student-focused” and she as a “learner/modifier” type of curriculum user. While these definitions are likely too simplistic to have much applicability beyond the walls of their two specific classrooms, the detailed descriptions of science teaching and learning within those walls are valuable evidence of how quality instruction can be provided to the highest possible level. They are not to be ignored.

SOURCE: Sarah J. Carrier et al., “Citizen science in elementary classrooms: a tale of two teachers,” Frontiers in Education (October 2024).

Thanks to the leadership of Governor DeWine, Lieutenant Governor Husted, and the Ohio General Assembly, high-performing public charter schools have in recent years received additional dollars through the Quality Community School Support Fund. These funds were designed to help narrow longstanding charter funding gaps that have made it difficult for quality charters to recruit and retain talented teachers and have stymied their ability to expand and serve more students.

Now in its sixth year, we at Fordham sought to examine whether the program has made a difference. Have the funding enhancements worked as intended—helping to strengthen charter schools’ instructional staff and improving student learning? Or has the program fallen short?

Join us at the Columbus Athletic Club to hear research findings from Stéphane Lavertu, Senior Research Fellow for the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and professor at The Ohio State University. In conjunction with the release of a forthcoming report, Dr. Lavertu will present his analysis about the impacts of the Quality Community School Support Fund. A panel discussion—panelists to be announced soon--and audience Q&A will follow the presentation.

Presenter

Dr. Stéphane Lavertu

Senior Research Fellow, Thomas B. Fordham Institute

Moderator

Chad L. Aldis

Vice President for Ohio Policy, Thomas B. Fordham Institute

Panelists

Anthony Gatto

Executive Director, Arts and College Preparatory Academy (ACPA)

Ciji Pittman

Superintendent, KIPP:Columbus

Charles Bull

Deputy Superintendent, Dayton Early College Academy (DECA)

Here is the full event video:

Under the bold leadership of Governor Mike DeWine and Lt. Governor Jon Husted, Ohio lawmakers enacted the Quality Community Schools Support Fund (QCSSF) in 2019. The program—the first of its kind in the nation—provides additional state dollars to support high-performing public charter schools (also known as “community schools” in Ohio). From FY20 to FY23, between 20 and 40 percent of Ohio’s 320-some charters met the state’s performance criteria and received an extra $980 to $1,600 per pupil, depending on the year. Though it’s too early to study its impacts, lawmakers in last year’s state budget further increased program funding starting in FY24.

QCSSF helps address longstanding funding gaps faced by Ohio charters, which have historically received about 30 percent less taxpayer support than nearby districts. This shortfall has exposed charters to poaching by better-funded districts that can attract teachers via superior pay. It has also limited charters’ capacity to provide extra supports for students, most of whom are economically disadvantaged and could use supplemental services such as tutoring. The gap has also required charters—even high-performers—to operate on a shoestring, leaving them little room in their budgets for expansion. Besides limiting these schools in practical ways, underfunding charter students’ educations by virtue of their choice of public school is simply unfair.

We at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute have proudly advocated for QCSSF. To be sure, even with the most recent boost in funding, it still doesn’t quite achieve the ambition of full funding equity for all charter students. But it does represent a big step forward. Given our support for the program, it might be surprising to see our interest in also evaluating it. Why put it under the research microscope and risk dinging it?

For starters, while you’ll often find us backing choice-friendly initiatives, we also seek programs that work for students. To that end, Fordham has commissioned studies that shed light on policies we broadly support (evaluations of private school scholarships and inter-district open enrollment being two examples). Sometimes the results are sobering—and have led us to pursue course corrections—and at other times, they’ve provided encouragement to press onward. In sum, we remain committed to rigorous analysis that helps policymakers and the public understand how education initiatives function and how they impact students.

We are also mindful that initiatives lacking follow-up research and solid evaluation are more susceptible to the chopping block. Consider one example. Back in 2013, Ohio lawmakers launched a brand-new, $300 million “Straight A” fund that aimed to spur innovative practices. The program was initially greeted with enthusiasm but just five years later it had vanished. One likely factor is that no one got under the hood to study the program, which allowed skeptics to more easily cast doubt on its efficacy. Without evidence to guide their decision-making, policymakers may well have assumed it wasn’t working and chose to pull the plug whether or not it was actually boosting achievement.

With this in mind, we sought to investigate—as soon as practically possible—whether QCSSF is achieving its aims. Conducted by Fordham senior research fellow and Ohio State University professor Stéphane Lavertu, this analysis examines the program’s impacts on qualifying charter schools’ staffing inputs and academic outcomes. The study focuses on data from 2021–22 and 2022–23—years three and four of program implementation—as the prior two years were disrupted by the pandemic. To provide the clearest possible look at the causal impacts of the extra dollars provided by QCSSF, Dr. Lavertu relies on a rigorous “regression discontinuity” statistical method that compares charters that narrowly qualified for QCSSF to charters that just missed meeting the performance-based criteria.

We learn two main things about the program:

Various factors could have driven the academic results, including the ability to implement high-quality curricula or tutoring programs with the QCSSF dollars. But we suspect a particularly strong connection between the reduced teacher turnover and the positive outcomes. Provided that turnover is not caused by efforts to remove low-performing instructors, studies indicate that high levels of teacher turnover—something Ohio charters have struggled with because of their lower funding levels—hurts pupil achievement. The QCSSF dollars, however, have allowed charters to pay teachers more competitive wages and retain their talented instructional staff—thus helping to improve achievement.

Leaders of high-performing charters (including those sponsored by our sister organization, the Fordham Foundation) agree that the additional resources have proven pivotal. Andrew Boy, who leads the United Schools Network in Columbus, said, “Since the addition of the QCSSF, we’ve been able to vastly improve teacher pay to attract and retain more effective, experienced staff, which allowed us to serve more students and deliver on our mission.” Dave Taylor, superintendent of Dayton Early College Academy (DECA), said, “We have used these funds to address key strategic areas of focus: increasing teacher compensation, ensuring we have high quality instructional materials in all classrooms, and taking control of our students’ transportation. The QCSSF has truly been instrumental in DECA’s ability not only to weather the challenges of the pandemic but to be well positioned to serve students well long into the future.”

The findings from this report should encourage Ohio policymakers to keep pressing for improved charter funding. They should also ease concerns voiced by skeptics that charters would not put these additional dollars to good use (“obscene profits on the backs of students is the charter standard,” one bombastic critic said last year). Au contraire: The charters that qualified for the QCSSF program used the funds primarily to boost teacher pay, and the result was that students benefited. Isn’t that something we can all cheer?

Fordham remains committed to fair funding for charter students and to shining light on the QCSSF program. Indeed, we intend to come back in the next few years with updated evidence on the program. But for now, one can confidently say that the program has so far worked as intended and driven improvement in Ohio charter schools.