School funding guarantees have been a much-discussed element of Governor DeWine’s proposed biennial budget. At a press conference unveiling his proposal, the governor stated: “It is time that…we no longer fund empty desks; we will not be funding phantom students.” True to his word, his outline dials back “guarantees,” which provide excess dollars to protect districts from funding reductions that are otherwise prescribed under the formula.

In his comments, DeWine alluded to the continuing enrollment declines in Ohio school districts as the rationale for reducing guarantees. Indeed, when districts serve fewer students, an enrollment-driven formula (which Ohio has) will usually prescribe lower funding levels than before. This is a perfectly rational and fiscally responsible approach. Hospitals should receive less public subsidy when they serve fewer patients. Spending on unemployment benefits should decline when more people have jobs. In a similar vein, governments should scale back funding when schools educate fewer students.

Yet hot on the heels of the governor’s proposal, school funding guru Howard Fleeter seemed to downplay the role of enrollment declines in guarantee funding. He told Gongwer, “This idea that the only reason you’re on the guarantee is that you’re losing enrollment, that’s the thing that I think is disingenuous.” In the Cleveland Plain-Dealer, he called it a “myth” that enrollment declines are driving guarantees.

Fleeter is correct that the “only” reason for being on the guarantee isn’t lost enrollment. Districts with increasing wealth—rising property values and resident incomes—also stand to lose state aid under Ohio’s progressive funding formula. To ensure that poorer districts receive more assistance, the formula prescribes them more funding. However, if a district gets steadily wealthier, its formula funding may be lower than in the past. That’s only fair.

Mason City Schools in suburban Cincinnati is the prime example of a district on the guarantee due to growing wealth. From 2020 to 2024, its local tax revenues soared from $59 to $96 million, a 64 percent increase that easily outpaces the statewide average of 18 percent. Underlying the rise in local revenues is a significant increase in property values (up 20 percent) and resident incomes (up 21 percent). The formula takes into account Mason’s rapid gains in local wealth, and in turn reduces its prescribed state aid.[1] However, the guarantee does an end-run around the formula and protects the district from that funding loss. This year, Mason received the largest guarantee subsidy in total dollars statewide ($14 million).

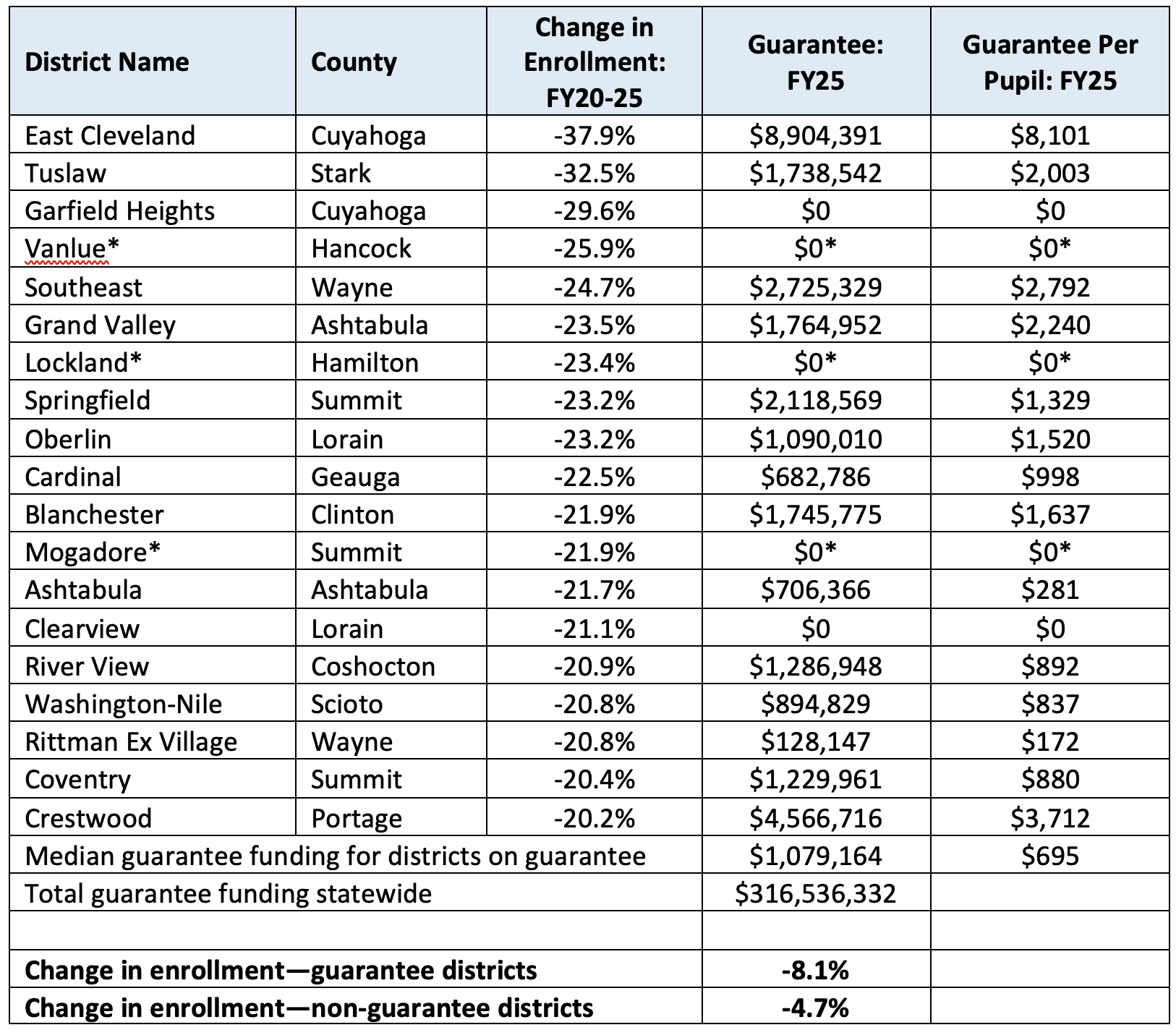

So yes, trends in local wealth factor into the guarantee. But enrollment remains a significant factor. Consider Table 1 which shows the districts that experienced the largest enrollment losses over the past five years (more than 20 percent). Fourteen of the nineteen districts are on the guarantee, while three more (starred) are on a guarantee that benefits very small districts and is tucked inside the formula’s “base cost” model.[2] Only a couple of the rapidly declining districts are not on the guarantee, likely due to slower growth in local wealth and other variables.[3] Looking at guarantee versus non-guarantee districts more broadly, the bottom rows of the table shows that guarantee districts overall have suffered larger enrollment loss within the past five years than their counterparts (-8.1 versus -4.7 percent).

Table 1: Districts with the largest enrollment declines and guarantee funding

Notes: Table displays the districts with enrollment declines of more than 20 percent from 2019–20 to 2024–25. The “guarantee” represents funds from the two main guarantees elements in the current system, known as “temporary transitional aid” (guarantees based on FY20 funding levels) and “formula transition supplement” (guarantees based on FY21 funding levels). (*) Denotes small districts (less than 750 students) that benefit from a staffing minimum guarantee embedded in the formula’s base-cost model, the amount of which is hard to determine.

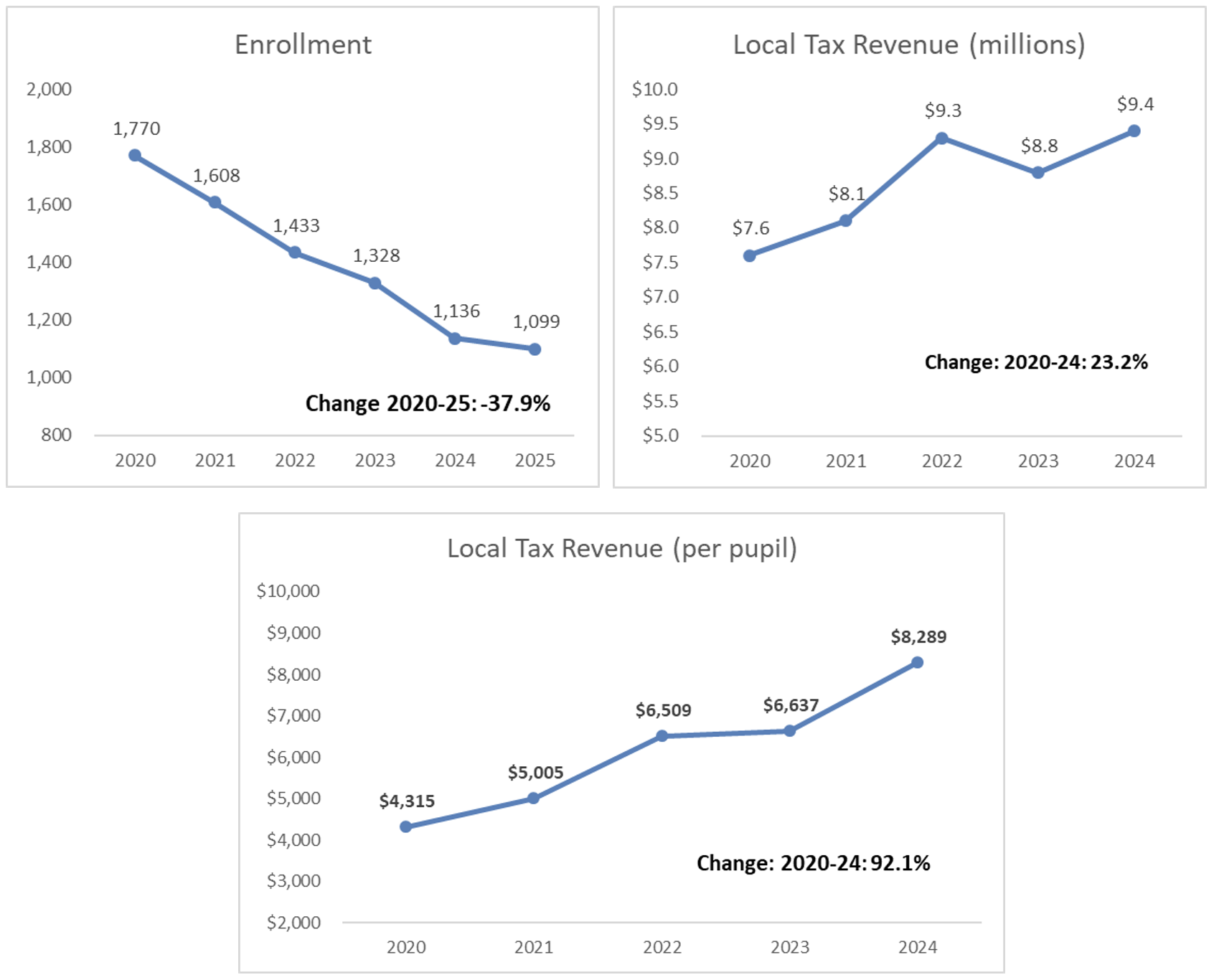

At the top of Table 1, we see East Cleveland. It is an undeniable example that sharp enrollment declines can put districts on the guarantee—proof that taxpayers are indeed funding “empty desks.” Over the past five years, the district has been the state’s biggest enrollment loser, shedding a remarkable 38 percent of students. To put it another way, in a classroom that once had twenty students, there are now eight “empty desks.” Despite its nearly half-empty classrooms, the district receives a massive subsidy from the state that amounts to an astronomical $8,101 per pupil in guarantees, the largest sum on a per-pupil basis statewide. Making things even more absurd, the district has actually gained in local wealth, which—when combined with the enrollment slide—has nearly doubled its local revenues per pupil.[4]

Figure 1: East Cleveland’s enrollment, local revenue, and local revenue per pupil

***

As you can tell, school funding is pretty complicated. But let me boil it down to three basic ideas when it comes to guarantees:

First, removing guarantees is a step towards a fairer school funding formula in which all districts receive state aid via formula. Conversely, guarantees only prolong Ohio’s “patchwork” system, where some districts are funded via formula, while others are on guarantees.

Second, giving guarantees to districts that have more local wealth undermines the core principles of a progressive, fair funding formula. Their budgets are growing thanks to increased local support, and the state should pare back its funding allotments and send them to districts more in need of the aid.

Third, districts serving fewer students should receive less state aid under a fair funding plan. Rather than propping them up—on the backs of taxpayers—Ohio should expect districts to tighten their belts when they are losing students.

In the coming days, if lawmakers can withstand the onslaught of the education establishment, we should get one step closer to a formula that is truly fair to schools, students, and the citizens of Ohio.

[1] Mason’s enrollment declined from 2020 to 2025 (-3.3 percent), which magnifies the increase in local funding on a per-pupil basis (up 69 percent).

[2] This refers to a “staffing minimum” that boosts the formula funding for low enrollment districts (under 750 students). Their helps to keep smaller districts—including those losing enrollment—off the main guarantees, since their formula prescriptions are more likely to exceed their historical funding levels (the previous formula did not include these minimums). The value of the staffing minimum guarantee is difficult to determine.

[3] Garfield Heights appears not to be on the guarantee due in part to a sizeable increase in DPIA funds. It now reports 99 percent “economically disadvantaged” students (due to CEP) versus just 55 percent in FY19, the last year the previous formula was functional. Clearview appears to have experienced a large increase in “targeted assistance,” suggesting that its local wealth has grown slowly compared to the median district.

[4] East Cleveland’s property valuation in FY23 (most recent available) was $161 million versus $138 million in FY20; resident incomes have also gone up in recent years.