Last month, Emily Hanford of American Public Media filed a withering indictment of reading instruction in U.S. schools. Her radio documentary, “Hard Words,” exposed how much “decades of scientific research” have taught us about reading—and how little of it has reached classroom practice via teacher training. Her conclusion was simple and unsparing: “Schools aren’t teaching reading in ways that line up with the science.”

Hanford is echoing arguments that have been made by a generation of researchers and advocates, but timing is everything: I can’t recall a similar reaction to any other recent piece about classroom practice. And it has legs. It’s been a month since the documentary was posted, but I’m still seeing teachers sharing and discussing it on social media daily. One such response, posted to the Facebook page of Decoding Dyslexia-Arkansas, was a letter from teacher Patricia C. James to the dean of the Arkansas State University, where she graduated with a double major in Elementary Education and Special Education. James wrote that, while her teacher preparation was mostly very good, she was “totally unprepared to teach reading, especially to the struggling readers that I had at the beginning of my career in my resource classroom.”

“Having been taught phonics in elementary school, I knew my students needed more than the Balanced Literacy ‘3 cueing strategy’ that basically encourages students to guess unknown words,” James wrote. “Reading should not be a ‘guessing game,’ which is exactly what Balanced Literacy and Whole Language reduces it to.”

Another educator, Susan L. Hall, the CEO of the 95% group, an educational consulting company, posted a link to James’s letter on Twitter and wondered what might happen if every teacher who felt ill-prepared to teach reading wrote a similar letter to their ed school deans. I second the motion and hope others will do the same.

Here’s my letter to the current dean of my ed school.

***

Dear Dean Rose Rudnitski:

On a shelf, three feet from my elbow, is my diploma from Mercy College, awarding me the lordly title of “Master of Science, Elementary Education.” It’s hard to look at it without wincing a bit. I mastered no effective literacy practices in the two years I spent in the “New Teacher Residency Program,” a program designed specifically for the New York City Teaching Fellows, the alternate certification program I joined in the summer of 2002. Nor was there very much “science” in my coursework. I’m grateful for the professional credential, which allowed me to enter the teaching profession. But if there’s anything one might expect an advanced degree in elementary education to include, it would be teaching reading. It wasn’t part of my program.

There is a science of reading and we owe it to all future elementary school teachers that it be taught and embraced so that it might improve outcomes for children. In his recent book Language at the Speed of Sight, cognitive neuroscientist Mark Seidenberg makes a pointed and persuasive case that “the principal function of schools of education is to socialize prospective teachers into an ideology—a set of beliefs and attitudes.” There is a radical difference between what he derides as the “culture of education” and science. The two have “different goals and values, ways of teaching new practitioners, and criteria for evaluating progress,” Seidenberg writes.

It’s hard not to agree. Last weekend, I dug out the thick portfolio of papers, written reflections, and student work samples that members of my cohort were required to collect and curate as indicators of the learning outcomes our masters program demanded. To earn my degree, I had to demonstrate my “passionate commitment to learning” and show proof that I was a “reflective practitioner.” Teaching the “whole child” required me to show that I teach “responsively” and “in context,” but there’s no visible evidence, in my portfolio or in my memory, that suggests any attention to psychology, cognitive science, language development, or the rich body of research in those fields that might shape our views of teaching and learning.

Indeed, if someone unfamiliar with our field had only my portfolio as evidence, they might conclude that the most important challenge a new teacher faces is not learning and mastering a body of professional knowledge or demonstrating skill as a practitioner, the hallmarks of a true profession like medicine or the law. They would likely assume that the key to classroom success is developing a “personal philosophical vision” of education—another of the essential outcomes I was required to articulate to earn my masters degree.

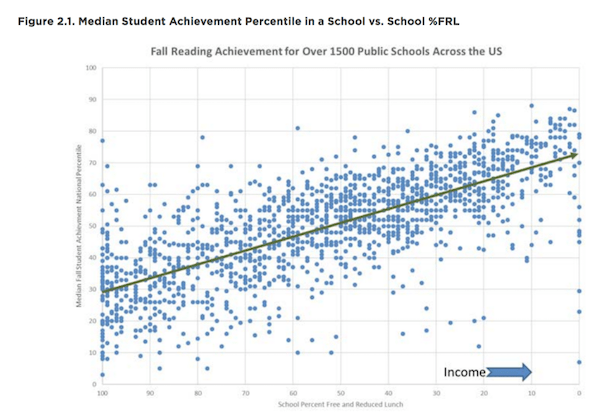

Emily Hanford’s radio documentary focused on the efforts of a school district in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, to diagnose and reverse the rampant reading failure in the district—and not just among low-income kids. “When chief academic officer Jack Silva was examining the reading scores, he saw there were plenty of kids at the wealthier schools not reading very well either,” Hanford reported. “This was not just poverty. Since he knew nothing about reading, he started searching online.” Dwell for a moment on that anecdote and what it portends. When the CAO of a school district, someone in a position of expertise and authority in an American school system, is in the dark about effective reading practice and has to Google it, it’s says something unsettling and alarming about the lack of a common professional knowledge base in our field. Ultimately Hanford’s documentary traces much of our failure not to teachers, but those who prepare us—or fail to. “Why aren’t kids being taught to read?” she asks. “Too many teachers, school administrators, and college professors don't know the science,” Hanford concludes. It’s cold comfort to know that my teacher preparation program at Mercy College—long on my development as a “reflective practitioner,” short on effective practice—was not anomalous. But that did not help my South Bronx fifth graders.

I don’t wish to be unkind. I remain deeply grateful for the efforts of my Mercy College instructors and mentors. Rereading many of the dozens of “moments that matter” reflection pieces I wrote in my first two years in the classroom are plaintive; some are nearly despairing. I’m impressed in retrospect at the humane and empathetic tone of the many and extensive handwritten comments on those papers. But I cannot help but wish that less attention had been paid to the development of my “philosophical vision” and willingness to “explore one’s deepest beliefs about teaching.” This is the language of ideology and religion, not the professional practice of a field grounded in science and research. It’s not what I needed to be effective. It’s not what my students needed from me.

Sincerely,

Robert Pondiscio