Despite pressures to upgrade the teaching and learning of “STEM” subjects (science, technology, engineering, mathematics), state standards for science, although often revised, remain, on average, mediocre—undemanding, lacking crucial science content, and chockablock with pedagogical and sociological irrelevancies. That’s the conclusion of Fordham’s most recent review of state science standards to which I contributed. To be sure, there are outliers: A handful of states have done justice to the importance and economic urgency of real science, to the needs of teachers as well as students. But a dreary low-C average for fifty states reveals their continuing failure to deal satisfactorily with standards for K-12 science.

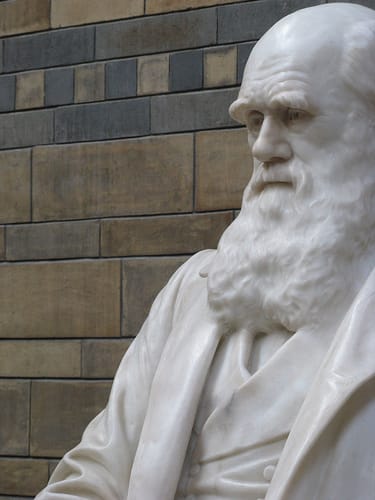

America's state standards continue to disrespect Darwin's contribution to science. Photo by Kevan Davis. |

There are, of course, multiple reasons for the low marks. Among these, the saddest and least justifiable is what the authors call “Undermining Evolution.”

Evolution science (grown over 150 years far beyond geology and biology) is by no means the whole of natural science. But it is a very important topic among the thirty or so that must be taught and learned in a school science program. It is central to all life science and one of its most active fields. Yet the reviewers find that, in many states, evolution is weakly, incompletely, even erroneously presented—unlike elements of other currently active areas such as modern physics or cell biology. Evolution is singled out in high-minded calls for “critical thinking,” for “strengths and weaknesses”—as though it were less reliable, less scientific, than the others! Basics of evolutionary biology are sometimes covered while the E-word itself, evolution, is avoided, or mentioned reluctantly in connection with high school (but not elementary or middle school) work.

Particularly dismaying is how rarely state standards indicate that evolution has anything to do with us, Homo sapiens. Even states with thorough coverage of evolution, like Massachusetts, avoid linking that controversial term with ourselves. Only four states—Florida, New Hampshire, Iowa, and Rhode Island—discuss human evolution in their current standards. This isn’t just a Bible Belt issue. Even the bluest of blue states don’t expect their students to know that humans and apes share ancestry.

Why? The answer is not the first one that springs to mind: religion. To be sure, religion—biblical literalism—is one part of the thrust to undermine standards for evolution. But politics is the other, probably more important element. A focused combination of politics with religion, in pursuit of (or opposed to) governmental action, is vastly more effective than either one alone.

A focused combination of politics with religion, in pursuit of (or opposed to) governmental action, is vastly more effective than either one alone.

Those eager to deny evolution for religious reasons are not just Christians who steer by every word of scripture. They include some (not all) fundamentalists of all three Abrahamic faiths, plus a very few anti-science academics. Understandably, the literalists don’t want children taught in school what must be falsehoods from their perspective. By themselves, however, religious anti-evolutionists would wield scant power over state decisions. Real power comes by politicizing the arguments and switching them from scripture to more stylish notions: “scientific alternatives,” “critical thinking,” or—most commonly—“strengths and weaknesses of [Darwin’s] theory.” When these are pressed by politicians dissing “Darwinism,” a downgrading of science is underway.

As the report notes, 2011 alone saw eight anti-evolution bills introduced in six state legislatures. Just this Monday, the Tennessee Senate passed a bill that would allow teachers to help students "understand, analyze, critique and review in an objective manner the scientific strengths and scientific weaknesses of existing scientific theories" like evolution. Last month, the Indiana Senate approved a measure that would allow the teaching of creationism. States from Oklahoma to New Hampshire have already considered similar legislation this year.

Whether such measures pass or fail (as most do), they can still have real effect on classroom teaching, on textbook content and selection, as well as on the curriculum as taught. All this political activity and the sense of popular support that it engenders can easily discourage teachers from teaching evolution, or from giving it proper emphasis—if only by signaling that it’s a highly controversial subject. Teachers, understandably, fear controversy and potential attack by parents. Meanwhile, for this and many other reasons, science performance of our children against their overseas peers remains average to poor.

The common anti-evolution claims are no more than talking points, less cogent even than the talking points of politics. The primary scientific literature has disposed of them all, as any serious reader can discover. Their real purpose is simply to cast doubt on evolution as a shaper of life forms. But there is no reasonable doubt that Earth is four billion years old and that life’s diversity emerged over eons in steps, usually small, driven by such (evolutionary) mechanisms as genetic change and natural selection.

The undermining of evolution recalls a 1989 point made by the polymath and fiction writer Isaac Asimov. It was long believed, he noted, that the earth is flat. Accumulating evidence then showed that it must be a sphere. Centuries later, it was shown that Earth is not quite a perfect sphere. It bulges ever so slightly at the equator and flattens slightly at the poles. But it would obviously be absurd to think or teach that a spherical Earth is as wrong as a flat Earth. That would be dismissing reality with a triviality. Nibbling with trivial arguments at the heels of evolution is similarly absurd. But it does tend to undermine science education.

Dr. Paul R. Gross is an emeritus professor of life sciences at the University of Virginia.