This weekend saw the passing of Siegfried “Zig” Engelmann. He was a giant among educators and a true social justice warrior. By that, I mean that he dedicated his life to improving outcomes for the disadvantaged, not that he was some great wet lettuce who opined about emotional labor and set his critics three books to read before he would discuss anything with them.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Engelmann took part in the largest educational experiment of all time—Project Follow Through. The aim was to give disadvantaged kids the best possible start to their education. The planned U.S. government funding was cut by congress, so what was intended initially to be a large-scale intervention was stripped back to an experiment. The idea was that of “planned variation.” Different groups would develop their own programs and implement them in different centers. Outcomes from the different programs would then be compared in order to see which was the most effective.

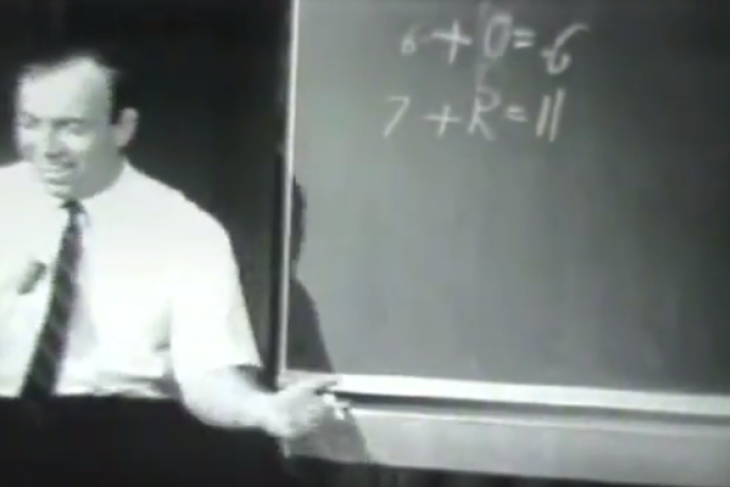

Engelmann and his colleagues developed the Direct Instruction model. This is not to be confused with just any form of explicit teaching. The Engelmann model had unique features that drew upon a specific theory of instruction and, controversially, employed the use of scripted lessons. Apparently, scripting the lessons was never the original intention, but the first teachers involved in the programs kept going off-piste.

Direct Instruction was the clear winner of the Project Follow Through experiment. Despite being labeled by researchers as a “Basic Skills” program, it was the best performer in terms of higher order cognitive skills, such as reading comprehension and mathematical problem solving, as well as the affective domain of student self-esteem. This is despite the fact that many competitor programs were explicitly set-up to focus on cognitive and affective skills; most of these actually had a negative impact.

This evidence has been largely dismissed by the educational establishment. Because it was so big, Project Follow Through was also messy, and so you can poke holes in the methodology. You might think that this would prompt academics to setup more rigorous trials of Direct Instruction and the alternatives, but they have been strangely reluctant to do so. This means that much of the further research on the method has been conducted by Engelmann and his small group of Direct Instruction advocates centered on the University of Oregon. This then provides another line of attack for those who wish to dismiss the research.

Why is it so important to dismiss Direct Instruction? It is inconvenient to the dominant ideology of educational progressivism or, latterly, constructivism. Who cares about kids’ life chances when there is an ideology at stake.

This means that an independent school like mine will make use of Engelmann’s programs, but his work is either unknown or dismissed in the schools and kindergartens he was trying to help.

I think all of us would like to leave the world a better place than we found it. Zig Engelmann certainly achieved this, but I cannot help feeling that it could have been even better if more of us had listened.

A version of this essay was originally published on the author’s blog, Filling the Pail. The present version was edited slightly per the Fordham Institute’s style guide.