Tenth grade Micky intently writes a hand-written apology letter on an old-fashioned desk. Today, he’s one of several students in his school’s new “Restorative Justice Room” (RJR). Scented candles burn in the corner and Mongolian throat singing plays quietly in the background. An eleventh-grader is daydreaming and cracking his knuckles. Another student, only in for lunch, rushes through her math homework.

The counselor was out sick today, so the dean of students Martin Philips filled in. “Our restorative justice system was missing something,” he explained to me. “And at first, we couldn’t pinpoint what it was. But then we discovered the missing piece: the ‘restorative act.’”

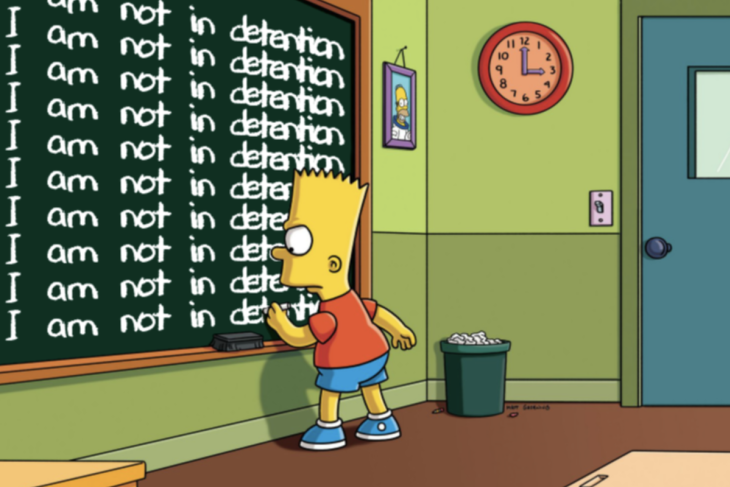

“It really varies by student and the behavior we are trying to punish—I mean, respond to,” he said. “For some, it might mean spending time in the RJR during lunch with similarly misbehaving peers. For others, staying after school and spending time in a classroom might help. For others, taking a ‘mental-health day’ at home has worked well.”

“We realized we are most likely to restore justice in the classroom when a student has some time to think about what they did,” Philips said. “We didn’t want them to miss class time, so it made the most sense to do it during all the other times.”

Two years ago, the school made a commitment to abolish any and all use of punitive discipline—detentions, suspensions, and expulsions, in particular. And Philips is proud to see that goal met.