Eli Hager and his colleagues at ProPublica have published some eyebrow-raising articles lately about Arizona’s universal education savings account (ESA) program. Most recently, Hager dug into its testing and accountability requirements—or lack thereof. When it comes to the public’s ability—and that of policymakers—to know whether Arizona’s program, or the schools and other vendors that it’s funding, are effective, there’s zilch, nada, nothing.

Yet Arizona turns out to be something of an outlier. Most school choice programs—including education savings accounts programs, especially those enacted in recent years—come with some testing mandates. Granted, there isn’t as much transparency or accountability as I’d like. As I told Hager, “If you’re a private school that gets most of its money now from the public…there should be accountability for you, as there is for public schools. If the public is paying your bills, I don’t see what the argument is for there not to be.”

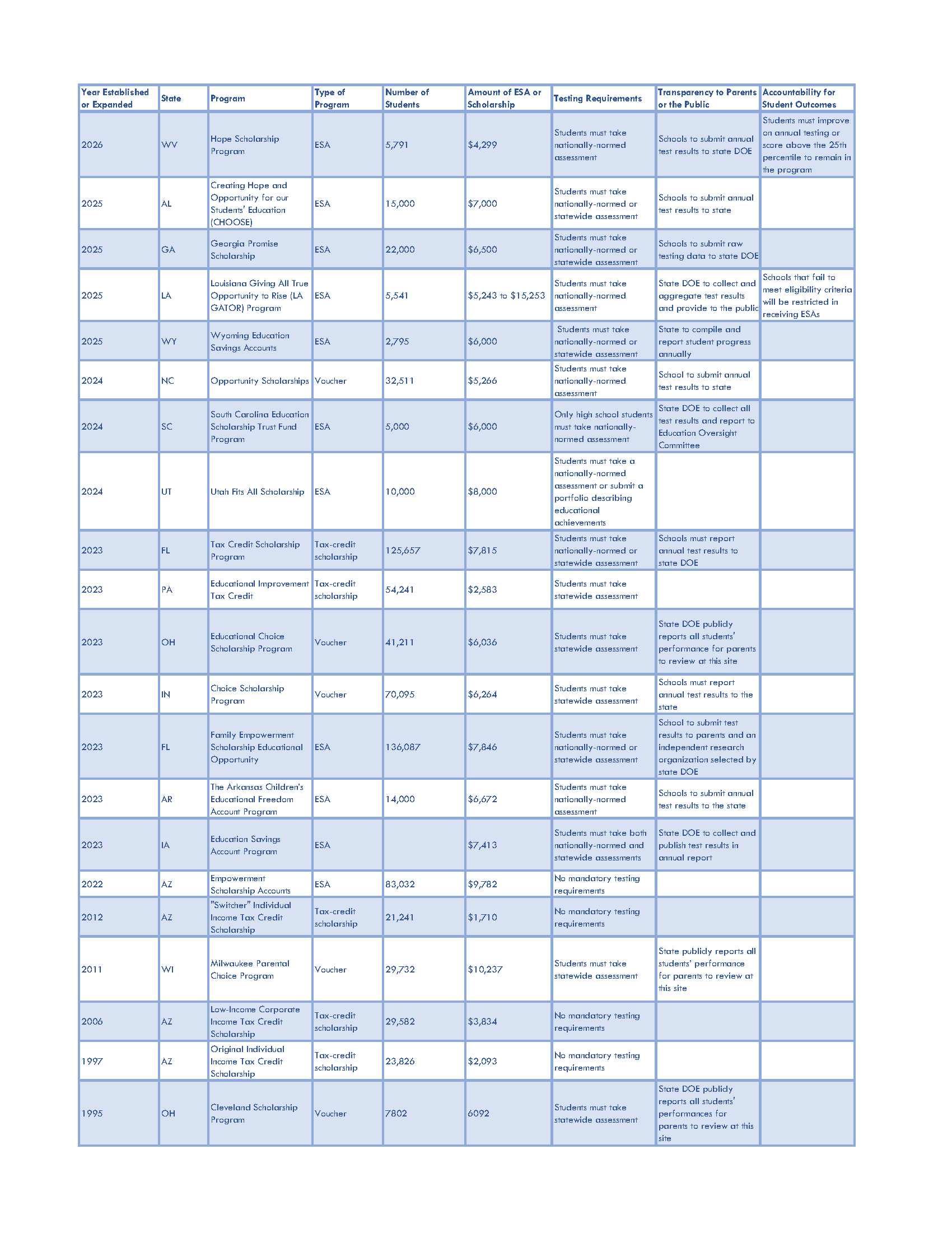

Yet in many other states, there’s more of it than conventional wisdom assumes. Table 1 provides a detailed look at testing, transparency, and accountability requirements, pulled from a recent Rand analysis, as well as Education Week, FutureEd, and (especially) EdChoice.

Since 2021 — the “Year of School Choice”— 15 states have created or expanded 16 large school choice programs. And the only one without a testing requirement is Arizona’s. Notably, 11 of the 16 programs are education savings accounts.

Moreover, if we look at all 21 programs included here (going all the way back to the 1990s), 15 include requirements to report test results to the state. As Rand recently argued, that means that high-quality studies of most of these programs should be feasible.

That said, whether the results are then reported to parents or disappear into a black hole is less clear. Only a handful of states — including Ohio, Wisconsin, and Louisiana — currently put school-by-school results on public websites. It’s hard to tell if the newer programs intend to do so in the future. If we want parents to be able to make school choice decisions using performance data, we need to do better.

As for accountability — kicking schools or other providers out of the program due to poor student results — there’s much less to report. Though given that there’s very little accountability for public schools these days, that’s not surprising. Indeed, we might be impressed that it exists in the private school choice sector at all. Louisiana, in particular, has long had a policy to remove schools from its programs for poor academic performance—a provision legislators maintained in its newest iteration. West Virginia, on the other hand, has a curious policy to kick students out of its program if they fail to make academic progress or land among the lowest-performing students in the state. I’m typically in favor of student accountability, but this version feels somewhat misguided even to me!

There are lots of arguments opponents make against education savings accounts, tax-credit scholarship programs, and other forms of private school choice. But the complaint that schools aren’t required to test their students is a charge that isn’t based in reality, save for a few exceptions. Consider the record set straight!

Special thanks to Fordham’s research intern Ali Schalop for her assistance in gathering and analyzing data for this article.

[1] Those serving more than 5,000 students; numbers for new or newly expanded programs are estimates. Tax deduction programs that offer a few hundred dollars in relief to cover homeschooling and similar expenses, as well as the (enormously complex) programs for students with disabilities, are excluded.