On June 22, the Dropout Prevention and Recovery Study Committee met for its first of three meetings this summer. The committee is composed of two Ohio lawmakers (Representative Andrew Brenner and Senator Peggy Lehner) and several community leaders. It was created under a provision in House Bill 2 (Ohio’s charter reform bill) and is tasked with defining school quality and examining competency-based funding for dropout-recovery schools by August 1.

Conducting a rigorous review of state policies on the state’s ninety-four dropout-recovery charter schools is exactly the right thing to do—not only as a legal requirement, but also because these schools now educate roughly sixteen thousand adolescents. The discussion around academic quality is of particular importance. These schools have proven difficult to judge because of the students they serve: young adults who have dropped out or are at risk of doing so. By definition, these kids have experienced academic failure already. So what is fair to expect of their second-chance schools?

Let’s review the status of state accountability for dropout-recovery schools and take a closer look at the results from the 2014–15 report cards. In 2012–13, Ohio began to provide data on the success of its dropout-recovery schools on an alternative school report card—a rating system that differs from that of traditional public schools. Dropout-recovery schools, for example, do not receive ratings for the conventional Performance Index or Value Added measures; neither are they assigned ratings on an A–F scale like other Ohio public schools. In 2014–15, the state began rating these schools as “Exceeds Standards,” “Meets Standards,” or “Does Not Meet Standards.”

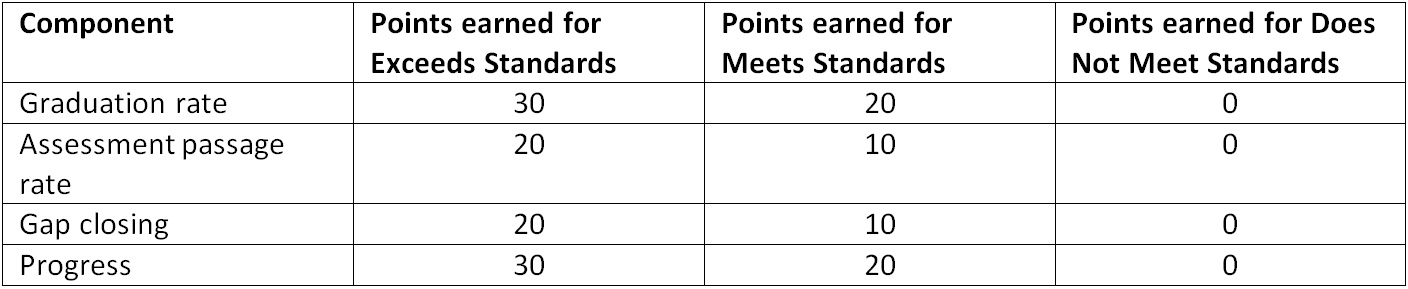

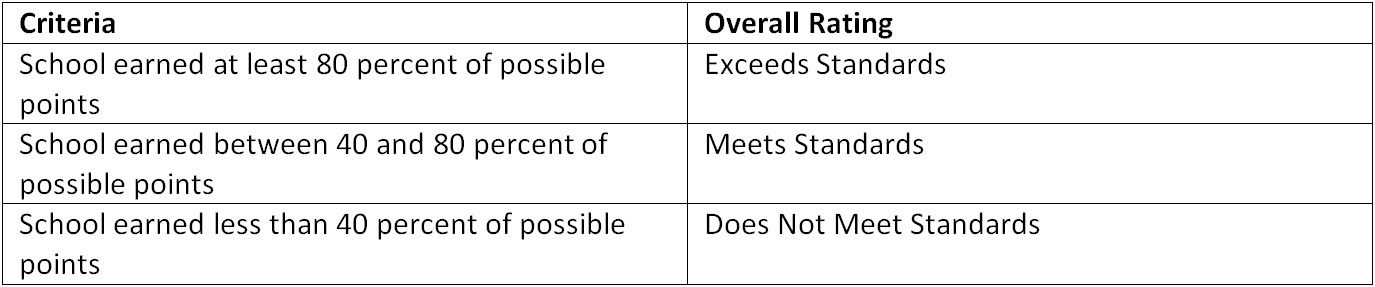

The overall grades are calculated by following a two-step process outlined in Tables 1 and 2. First, points are assigned to schools based on the four individual report card components: graduation rate (a composite of the four-, five-, six-, seven-, and eight-year adjusted cohort rates); the twelfth-grade assessment passage rates on all of the Ohio Graduation Tests or the end-of-course assessments once they are phased in; gap closing (a.k.a. Annual Measurable Objectives); and student progress. Each school receives a rating of Exceeds, Meets, or Does Not Meet for each component; points are awarded based on that designation.

As you can see from Table 1, the graduation rate and progress components are weighted somewhat more heavily than other two (30 percent versus 20 percent). Once all component points are added and divided by possible points earned, Table 2 can be referenced to determine which rating a school receives. When it came to overall school ratings for 2014–15, 43 percent of dropout-recovery schools received a Does Not Meet rating, 49 percent received a Meets rating, and 8 percent received an Exceeds rating (a total of ninety-three schools were part of this accountability system).

Table 1. Points assigned to DOPR schools based on component ratings

Table 2. Overall ratings assigned, based on the summation of points earned per category

The graduation rate, assessment passage, and gap-closing measures generally mirror traditional school report cards (though with some modifications). But one of the more interesting aspects of the dropout-recovery report cards is their progress measure (i.e., student growth over time). To measure student growth, dropout-recovery schools use NWEA’s Measures of Academic Progress (MAP) test rather than calculating gains on state exams. (State law specifies the use of a “nationally norm-referenced” assessment to measure progress in dropout-recovery schools. [1]) To gauge progress, dropout-recovery students must have taken both the fall and spring administrations of the MAP test. The differences in achievement from fall to spring are compared to a norm-referenced group (provided by the vendor) to generate an indicator of a student’s academic progress. Consistent with Ohio’s value-added measure, progress is evaluated based on whether a student maintains his relative position from one test administration to the next. In general, a student scoring at, say, the fiftieth percentile in one testing period would be expected to remain at that percentile in the next one. Achievement above or below expected growth classifies a student as exceeding or failing to meet expectations.[2]

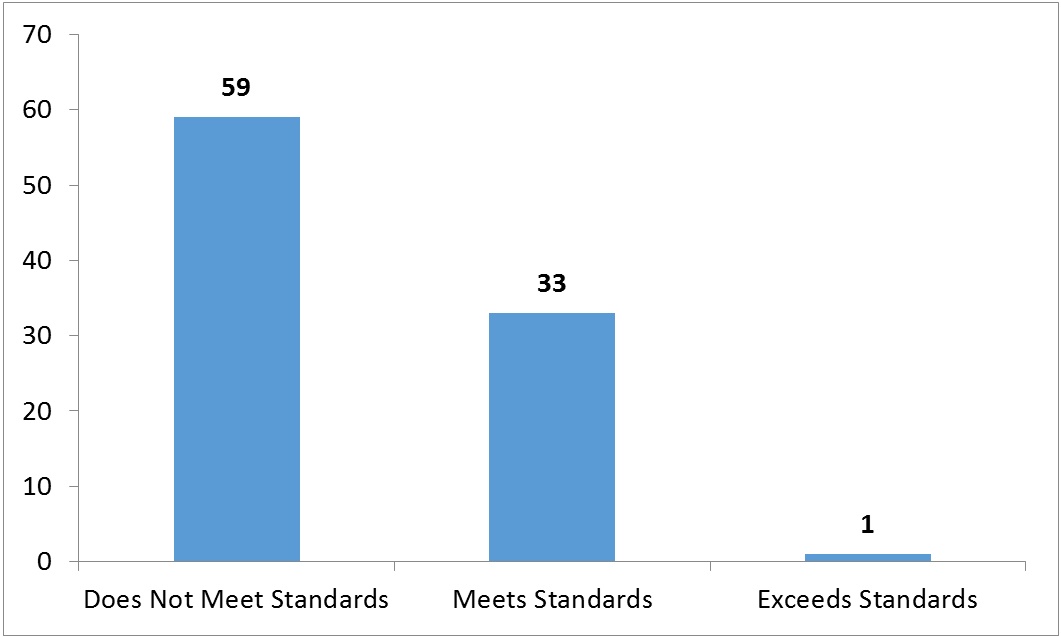

While the norm-referenced approach makes sense in the dropout-recovery context, the results from the first year of implementation appear oddly distributed to us. Consider Chart 1, which displays the number of dropout-recovery schools and their progress ratings. While fifty-nine schools did not meet the progress standards, just one—one!—school exceeded the growth standards. (Another thirty-three schools met the growth standards.) It should be noted that students failing to take both administrations of the MAP test are not counted in a school’s overall progress measure, so the disappointing results probably cannot be explained by either mobile or chronically absent students who didn’t take one of the MAP exams.

Chart 1: Progress ratings for Ohio’s dropout-recovery charter schools, 2014–15

Unlike the chart above, traditional district schools’ value-added scores demonstrate a wide range of scores and ratings (see here, for instance). However, because kids in dropout-recovery schools have experienced previous academic difficulties, we might expect their progress to lag behind that of their peers. Still, it seems strange to observe virtually no schools exceeding the growth expectations. It is worth investigating whether these results would be observed using a different value-added measure (such as the one used by districts, which compares a student’s performance to his previous test scores instead of a national norm). State policy makers should also confirm that the comparison group used by NWEA is appropriate for Ohio’s dropout-recovery students.

Further, confirming that a large enough sample size was used to generate these results is imperative. But it’s hard to identify the cause of this odd distribution. It could be related to methodology; or perhaps the average student in most dropout-recovery schools really is failing to achieve adequate progress. This question—along with a host of others surrounding dropout-recovery and prevention school attendance, funding, and “success”—should be addressed by the Dropout Prevention and Recovery Study Committee. To be sure, this is just one year of data, and a first using this type of growth measure. But policy makers should definitely look into these issues and keep a close eye on the 2015–16 progress results to see if the pattern recurs.

The dropout-recovery and prevention report cards provide essential accountability for Ohio’s alternative schools and offer much-needed information to parents, educators, and the public. The nature of dropout-recovery programs as second-chance schools begs the question of whether their success and progress should be measured with a different stick, but adjustments in report card composition and its measures account for the unique population they serve. Now we must confirm that the measures are useful and accurate as we seek to hold schools accountable for the job they were created to do: educating and graduating students who have fallen behind. Here’s hoping the Dropout Prevention and Recovery Study Committee prioritizes the accurate identification of dropout-recovery schools that are making a positive impact, confirming that the accountability system is working as it should.

[1] Unlike the value-added measure, which uses Ohio’s statewide achievement distribution as a reference group, the dropout-recovery measure is using a national norm-referenced population. For more details, see ODE/SAS, “Value-Added Measures for Dropout Recovery Programs” (May 2015).

[2] A growth score of less than -2 equates to a dropout-recovery report card Does Not Meet rating; a score between -2 and +2 equates to a Meets rating; and a score greater than +2 equals an Exceeds rating. These “cut points” are similar to the ones used for traditional public schools’ value-added measure. It is not exactly the same, however, due to the three-tiered rating system used for dropout-recovery schools.