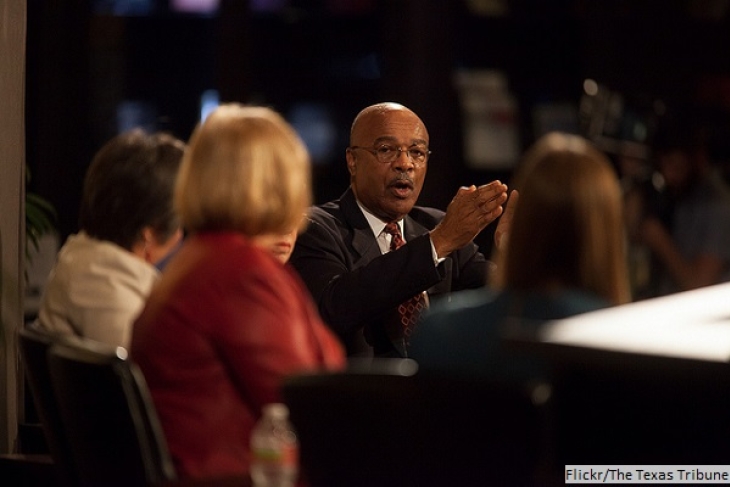

Editor’s note: On Monday, the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools inducted Rod Paige into their Charter School Hall of Fame. Rod’s contributions to education date back over half a century. Most notably, he rose to national prominence as the superintendent of the Houston Independent School District and was appointed the first black secretary of education in 2001. The Fordham Institute is also proud to have him serve on our board of trustees. This is the first half of a two-part interview (second half is here) he conducted with our own Alyssa Schwenk.

Alyssa Schwenk: The first charter law was passed in 1991, and Texas's charter law passed in 1995. When you were the superintendent of the Houston Independent School District, do you remember the first time you heard about charter schools and what you thought about them?

Secretary Rod Paige: A couple of years before that, I read about charter schools in the press, and the idea impressed me even before the Texas legislature started to talk about it. I was excited about the idea because I thought it was a way to increase innovation in schools, a way to unleash the ideas that a lot of teachers and principals had who had been constrained by bureaucratic regulations. This was freedom to innovate, to turn loose new ideas.

There was an elementary school in Houston called Wesley Elementary School. Wesley Elementary was led by an innovative principal named Thaddeus Lott. He was constrained by some of the system’s regulations, and it was a cause of conflict between Thaddeus and the central administration. When I became superintendent of schools, I noticed Thaddeus’s creativity and wanted to find some way to free him. So we stole from the idea of charter schools that I had read about in the press. The, although there was no charter school law in Texas, we asked the school board to charter a group of three schools: two elementary schools and one middle school in Houston Independent School District. We asked the HISD board to charter those three schools to Thaddeus Lott. And so we had the Lott schools well before—well, not well before, but about a year before—the law was passed in Texas.

AS: Was everyone on board with this decision? Did you need to get any buy-in? How did you frame the need to charter this school and free Mr. Lott and his team from the constraints of the current model?

RP: Well, first thing, there was no model. So we were flying by the seat of our pants, and we created a charter law based on what we thought it should be. And that was asking the board to give Lott the authority to, in a sense, govern for two elementary schools and a middle school. We gave him a budget for those schools and provided him freedom from the bureaucratic system that we had in the HISD at that time. Of course, we talked to the community about it and had the state legislator who was in that area at the time, who is now the mayor of Houston [Sylvester Turner], support it.

AS: What lessons did you bring with you when you came to Washington to be secretary of education?

RP: Well, Washington is pretty much locked into a culture of consent as well. And so in Washington, we tried to focus not on the whole deal, but on trying to improve reading and math, because we knew that reading and math were foundational for other accomplishments and other cognitive developments. A lot of those ideas were embedded in the No Child Left Behind Act.

AS: What do you think is the biggest legacy of No Child Left Behind for charter schools? Is it the focus on reading and math or something in the governance structure?

RP: Well it is important because it gave some possibility of support for charter schools, funding, and also some of the regulatory ideas. It didn't go nearly as far as we wanted it to go because, as you understand, federal policy involves so many different people, so many different ideas. So much of the No Child Left Behind Act was a result of negotiations with other people who had different ideas. In fact, much of the No Child Left Behind Act that was actually passed was not our ideas but the ideas of others—specifically Mr. [George] Miller and Senator Kennedy.

AS: What's one thing that's surprised you, either the charter field in general or for you personally, as you have watched charter schools evolve?

RP: I'll tell you a little story. The biggest problem for [KIPP founders] Levin and Mike Feinberg and their ideas for developing charter schools, I thought, was going to be finding quality people: quality teachers, quality principles, quality administrators. High-quality people who had the kind of missionary zeal that these two gentlemen had. I wasn't sure that that population existed. And so I was totally surprised by the high-quality people that wanted to work in good charter schools. Teach For America is another example of that. There is embedded in a large number of young people the need for a vehicle to express their appreciation for this country, to do good, and to make positive contributions. And so I have learned that the world is full of those kinds of people. I was surprised at the quality and quantity of them.

AS: And finally, you have been involved in almost every step of the process so far. What is your proudest legacy or specific accomplishment in the charter school movement?

RP: Well, just the total pride to see the progress that they are making. I'll tell you, it even exceeds my vision. I thought it was a great idea, but the idea is even stronger than I thought. I am also so proud of the young people who want to serve. Teach for America and charter schools are providing opportunities where they can express themselves, and I think that we should not tie students to schools that are not serving them well. And students should have a chance to experiment with those ideas and to see if they work. If they work, we should support them, and if they don't work, we should close them down.