[[{"fid":"114793","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default"},"type":"media","link_text":null,"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-default"}}]]

A school district should never go broke. But unfortunately, they can, and do. Take Pennsylvania’s beleaguered Chester Upland School District. Teachers will once again work for free as the district faces a $22 million deficit, which the Washington Post reports could grow to $46 million. The district of approximately three thousand students was first tagged as “financially distressed” in 1994, and since then, its enrollment has declined by nearly 60 percent even as special education costs have risen substantially. Neither of these developments came as a surprise. Yet the district still overspent its coffers by $45 million between 2003 and 2012, despite millions in few-strings-attached bailouts by the state over the same period. In 2012, Chester Upland ran out of money completely and the teachers agreed to work without pay; that same year, the state finally enacted legislation to do something other than hand out more cash. Under Act 141, the state could declare small districts in financial distress, allow them to apply for loans, and appoint a chief recovery officer (CRO) to oversee finances.

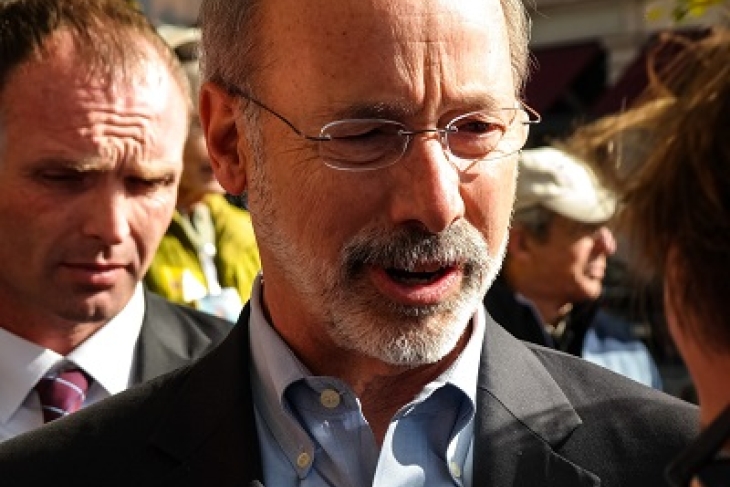

Since 2010, Chester Upland has received $75 million (an enormous sum, considering that its yearly budget is somewhere around $120 million); and yet its deficit persists. Only now is Governor Tom Wolf proposing direct interventions in the form of appointing a financial turnaround specialist, requiring the district to submit to a financial audit, and mandating significant changes to district spending.

Compare Chester Upland to Philadelphia, twenty miles up Interstate 95. In 1998, then-Superintendent David Hornbeck threatened to shut down the financially strapped district and filed lawsuits to force the state to provide additional funding. The state responded with an emergency bailout Two years later, it enacted a law allowing it to replace the local board with a School Reform Commission (SRC), though only in “first-class” districts (those serving cities with at least one million residents, which only included Philadelphia). The state department of education then signed a “Declaration of Distress” for Philadelphia, and since then, several hundreds of millions of dollars have flowed into the district. Yet even these haven’t saved Philadelphia schools from financial trouble; the district projects a deficit of nearly $85 million at the end of FY 2016.

Chester Upland and Philadelphia are two sides of the same policy coin. Our recent brief Who Should Be in Charge When School Districts Go into the Red? outlines a tiered system of strategic, proactive interventions for districts in distress. The first tier gives local leaders collaborative supports to manage finances; for example, an outside expert or a review committee comes in to identify areas of overspending. These low-level, non-punitive interventions are triggered at the first indication of potential distress. Should leaders prove unwilling or unable to follow the expert advice, the district enters the second phase, during which a state-appointed financial manager has complete control over district spending. The third tier is a complete administrative takeover of the district--the superintendent and board are removed, and an appointed leader or panel controls all district operations. Large grants or long-term loans are contingent on districts entering this final phase and replacing their leadership.

Pennsylvania’s policies run against our recommendations. They are not tiered, they are not proactive, and they certainly are not strategic. Chester Upland operated with a deficit for far too long, and its leaders received emergency infusions of cash without a requirement that they address underlying problems. When finances went from bad to worse, it finally received a large emergency loan and a CRO, but without a substantial change in leadership. The superintendent and board remain, as do the spending problems. Even with the CRO, there is little oversight on how state money was spent, and an audit is only proposed at this point. Governor Wolf’s actions with Chester Upland are too little, too late. Although he is arguably compensating for a slow-moving legislature that has yet to enact any smart policies, Chester Upland needed to be fully managed by outside experts years ago.

At the same time, Philadelphia has the SRC, which replaced the board, to plan and manage its finances. Yet in the past fifteen years, while the district has regularly run deficits in the hundreds of millions, it has more than once relied on stopgap loans or one-time infusions of revenue. Since the takeover, it has also seen six SRC chairs and seven superintendents.

School districts need concrete policies in place that identify signs of financial risk and trigger a well-defined series of interventions of increasing severity when those signs are found. Leaders must first be given assistance on how to project future costs and adjust accordingly. External advisors can also give district leaders political cover to make unpopular decisions. But before districts reach the “years of failure” mark (and before they amass millions in bailout funds), leaders must be replaced by the state. Complete financial meltdowns like the one in Chester Upland can be averted via strategic, proactive interventions that leave little room for “let’s wait and see.”

gsheldon/iStock Editorial/Thinkstock