During a political campaign, the savviest candidates excel at two things. First, they offer a compelling message that differentiates them from their competitors. Second—which demands true skill and sophistry—they ascribe all their own failings to those very same competitors, forcing them to answer for political, policy and social issues for which they are not responsible. To restate: You blame the other guy for things you did and hope it sticks.

While the presidential contest among Democrats (the hoop-jumping is worthy of a summer community pool), and the battle between traditional public schools and public charter schools for which it has become a proxy, may lack much in the form of clear differentiation, it features the blame game that powers the second strategy aplenty. In the race to woo teachers unions and white progressives who love their neighborhood public schools, charters have become the bête noire of the education discussion, the thing where all the ills that ail our country intersect. Segregation, school finance woes, civil division, teacher turnover and pay—the Mandarin immersion charter school down the street and the one that is really excellent at closing achievement gaps for kids of color are clearly responsible for it all, right?

There’s just one problem: It’s not true. In fact, we need look no further than the nation’s traditional public schools to see who bears responsibility for the continued perpetuation of these issues.

Some candidates have excoriated charter schools for being engines of segregation even though the research does not bear this out. The blame for school segregation, however, lies not with charters but with neighborhood schools themselves and the pernicious history of redlining that segregated them in the first place. Consider that the Home Owners Loan Corporation, a creature of post-Depression New Deal national policy, delineated neighborhoods where residents could receive mortgages and neighborhoods where they could not, identifying the latter in red. It is no secret that the red neighborhoods were also filled with black people.

This policy and its racist leanings not only exacerbated neighborhood segregation, it was a foundational precursor to the neighborhood public school attendance zones of today and, notably, the platform for schools that are more segregated now than they were in the pre-Brown era.

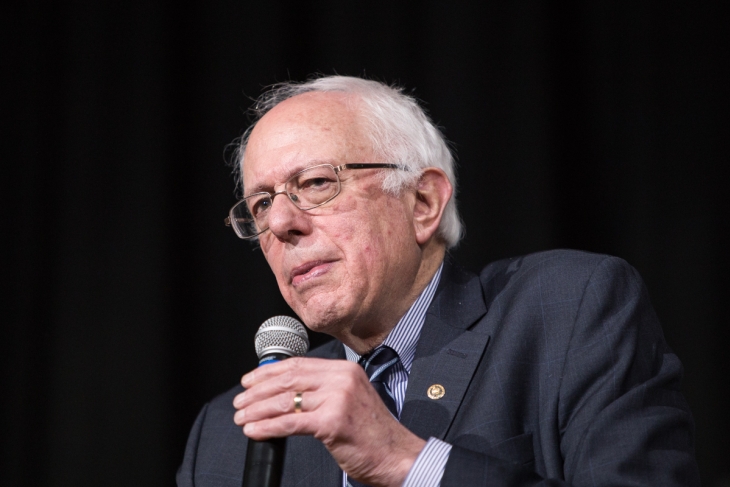

To prove the case, it’s helpful to examine a place where the effects of charters (or private school choice, for that matter) don’t exist. Nebraska, for instance, has no charter schools. Despite their absence, the state features 25 of the country’s most segregated—both by race and by wealth—public school district borders. Yet attacks on this perpetually segregated system of public schools, the one we actually have, seem absent from candidate campaign literature. Why is that? Sen. Bernie Sanders, for instance, has made “charter school segregation” a pillar of his campaign platform. His home state, Vermont, is 94.2 percent white, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, and 1.4 percent African American, and has no charter schools. Can Sanders even credibly comment on this issue?

Some offer that charters undermine the nation’s public school finance mechanisms, but the same housing covenants that segregated the public schools are also at play here. As the professor Dorothy Brown divined, homes in majority-black areas appreciate less than those in majority-white areas. Not only does this mean the tax base of majority-black areas is lower—resulting in less ability to tax local property to raise wealth for local schools—it also has crippled the ability of black families to accrue household wealth compared to their white peers. Only Hawaii does not feature a property tax component for its public-school finance schemes. With every other state relying on valuations of property that have been systematically depressed by decades of race-motivated local and federal policies to fund schools, it’s difficult to argue that issues of equitable funding find their root in a charter school effort that is barely a quarter-century old. It’s also hard to rationalize the decision to fund schools this way unless one set of schools is necessarily meant to be funded better than another.

While lip service to this disparity by presidential candidates nods toward equalization, none of it attacks the underlying factors of neighborhood assignment that catalyze and exacerbate the conditions themselves.

Ironically, although the appetite to eliminate charters may be intensifying among progressive whites (as the schools remain very popular among African Americans and Hispanics), the desire to increase public school funding is mixed. While some red states such as Arizona have added billions to their budgets to increase public school revenue (and in Arizona, specifically, teacher pay) deep-blue Los Angeles rejected a tax hike to increase public school funding in the wake of one of the country’s most disruptive teacher strikes. If you’re not an ideologue, it’s easy to see that something else is at work here and that this is all more complicated than what happens when a family chooses a charter school.

But if the facts don’t support your position as a candidate, you might dispense with the pleasantries and go straight for demonization in a self-interested effort to improve your flailing candidacy and curry favor with the anti-charter lobby. Which is to say you might be status quo handmaiden Bill de Blasio, whose own political situation knows two sorts of extremes: that of anti-charterism and that of the deep disinterest of the Democratic primary electorate he currently courts.

New York City, where de Blasio is sometimes present to be mayor, features one of the nation’s best charter school sectors in a state with one of its best charter laws. Approximately 10 percent of the city’s students attend charter schools. Their collective population is overwhelmingly low-income and minority. Their results are among the country’s best.

There’s nothing like success happening in your presence—despite your opposition—to turn your resistance up to 11. Candidate de Blasio recently informed attendees at a campaign event that he “hates” charter schools. During his first term, as he struggled to gain the favor of the United Federation of Teachers (which did not support his candidacy), he at least pretended there were two universes of charter schools: those that played by the rules he liked and those that did not. The presidential race has, however, removed this fig leaf of difference and liberated him to attack the schools that 1 in 10 city students attend (chosen by untold numbers of voting adults who are their parents). This flip-flopping is not a surprise to New Yorkers, as the one thing most consistent about candidate de Blasio and his school policies is their inconstancy. He once valorized school integration before saying a family’s choice to buy a school and a house together mattered more. His schools chancellor, Richard Carranza, opposes “screened” schools and sees them as engines of segregation, yet he sent his own child to one in San Francisco.

And de Blasio opposes the admissions requirements at the city’s flagship selective high schools (Stuyvesant, Bronx Science and Brooklyn Tech, specifically), in theory because too few African-American and Hispanic students gain entrance to them. His opposition to the policies seems newly found, however, given that during his first term, his own son graduated from Brooklyn Tech. It’s also politically expedient to focus on these schools—which he does not control and whose admissions requirements must be amended in Albany—instead of the balance of the selective high schools which he does control and for which the admission requirements could be changed tomorrow. If you called candidate de Blasio’s positions on these issues of school choice wildly inconsistent, you’d be generous. If you called them deeply self-interested and elitist, you’d be spot on. If you called them detrimental to kids in New York and across the country, you’d simply be calling it as it should be seen.

There is other unfortunate moderating taking place among the candidates, though my own Sen. Cory Booker’s latest hand-wringing over the charter issue disappoints me most, given the success of Newark’s charter schools (and coincident improvement in the city’s traditional public schools), which serves as a close backdrop to his own political narrative. But the education race for the presidency does leave us with two fairly clear takeaways. The first is that the nation’s charter schools are not responsible for conditions the traditional public schools themselves have created and continue to perpetuate, and if candidates are serious about tackling those issues, it will require a degree of intellectual and historical honesty that much of the primary debate has lacked so far.

The second is that, instead of apologizing to the public school industrial lobby that is working to unwind choice for millions of American families, they should be apologizing to the rest of us for supporting a schooling agenda that de facto makes parents and students less free, provides fewer working opportunities to teachers, confounds the ability of cities and states to make new public schools to solve local issues, and big-boxes public education in a way no progressive would ever support.

They say one size doesn’t fit all … a bunch of distortions about charter schools won’t fit, either.

Editor’s note: This essay was originally published by The 74.