As my colleague Sara Mead has written, we recently completed an analysis of state policies that affect charter/pre-K collaboration. In the analysis, we tried to figure out what a charter school would need to do and know in order to access state pre-K funds. In each state, we ask: Can charter schools offer state-funded pre-K? What’s the process for doing so? And how many charter schools serve preschoolers?

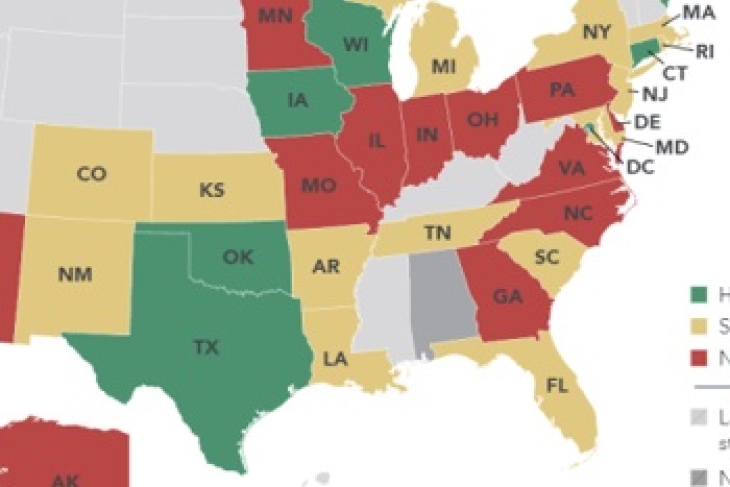

We used this information to rank states based on how hospitable an environment they offer for charter schools seeking to serve preschoolers. There are a few states where it is relatively easy for charters to offer pre-K. Washington, D.C. and Oklahoma top our list, with Wisconsin and Texas close behind. In these states, charter schools are one option in a network of diverse pre-K providers.

But in a majority of states, charter schools face numerous barriers to offering pre-K. Lots of these barriers are common across states, while others are unique to particular states. For example, low pre-K funding (less than 75 percent of what charters receive to serve K–12 students) creates a disincentive to offering pre-K in twenty-two states (and affects all potential providers, not just charter schools).

Nine states prohibit charters from offering pre-K at all. In some of these states, the charter legislation limits—intentionally or not—the ages or grades that a charter school can serve. Ohio’s legislation says that charter schools can only admit students between the ages of five and twenty-two; Arizona’s says that a charter school must provide instruction for “at least a kindergarten program or any grade between grades one and twelve.” In other states, such as North Carolina, the charter and pre-K laws aren’t explicit, but the state interprets that to mean that charters can’t serve preschoolers.

In many states, different pre-K programs, state offices, or administrations have different rules. Charter schools in Connecticut can’t access funds through the School Readiness Program, the primary state-funded pre-K program; but if their charter includes pre-K, they receive state per-pupil funding for preschoolers just as they do for K–12 students. In Pennsylvania, Governor Tom Wolf’s administration recently cancelled a charter school’s pre-K program, saying that state law prohibits charter schools from offering pre-K and the school was only allowed to provide the service due to an “oversight in the chartering process during the previous administration.” In Georgia, the agency that administers the state pre-K program explicitly allows charter schools to apply for pre-K funding, but the state charter office won’t allow it.

Despite these barriers, at least one charter school in most states has “made it work,” figuring out a way to serve preschoolers even without state funding. In states like Georgia and Arizona, some charters serve preschoolers through an “affiliated program”—a separate (usually nonprofit) entity that is affiliated with the school. Up until recently, this was the only way charter schools in New York could serve preschoolers. Other charter schools fund pre-K services through philanthropy, tuition, Title I funds, or general operating revenues. Sometimes the solution creates more problems, however, which is why we believe the best route is to enable charter schools to offer pre-K. Most states have a lot of work to do.

Ashley LiBetti Mitchel is an analyst at Bellwether Education Partners. This piece was originally posted on Bellwether’s Ahead of the Heard.