There’s no shortage of bad news in education these days, nor any dearth of stasis, but at least education reform is a lively, forward-looking enterprise that gets positive juices flowing in many people and that is leading to promising changes across many parts of the K–12 system. We are focused on making things better—via stronger standards (Common Core), greater parental choice (vouchers, charters, and more), more effective teachers (upgrading preparation programs, devising new evaluation regimens) and lots else.

When it comes to pension reform in the education realm, however, it’s hard to stay positive. Here, we’re saddled with a bona fide fiscal calamity (up to a trillion dollars in unfunded liabilities by some counts) and no consensus about how to rectify the situation. No matter how one slices and dices this problem, somebody ends up paying in ways they won’t like and perhaps shouldn’t have to bear. All we can say is that some options are less bad than others.

Today’s new Fordham study examines how three cities (and their states) are apportioning the misery—or failing to do so. This analysis pulls no cheery rabbits out of a dark hat, but it definitely illustrates the nature and scale of the pension-funding problem and describes a couple of painful yet, in their ways, promising solutions (or partial solutions) to it. As you will see in the summary report (by Fordham’s Dara Zeehandelaar and Amber Winkler) and several technical papers to follow, economist and pension expert Robert Costrell and education-finance expert Larry Maloney parsed the budgets of the Milwaukee, Cleveland, and Philadelphia school districts to estimate just how big an impact their pension and retiree-health-care obligations will have on their bottom line in coming years. (The Philadelphia paper is also now available on our website.)

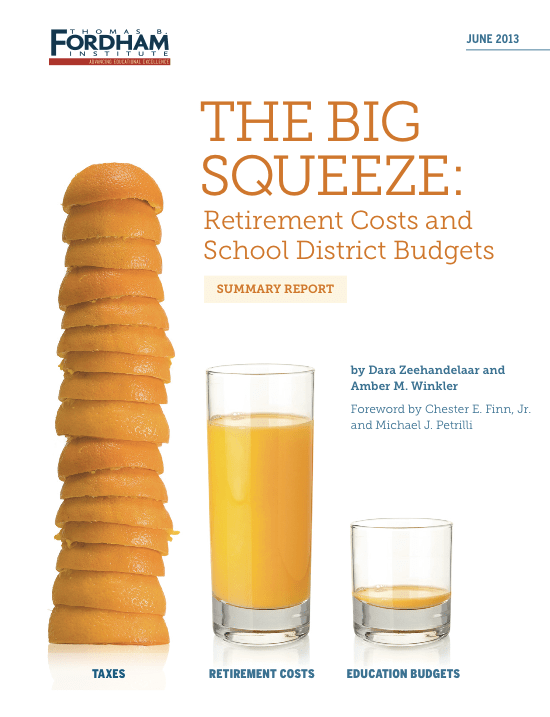

This is hardly an academic exercise. As our title indicates, these obligations are putting “a big squeeze” on district budgets. In Philadelphia—today the most threatened of the three districts—our analysts estimate that the school system could find itself spending as much as $2,361 per pupil by 2020 on retiree costs alone. That represents a staggering increase ($1,923) from its current level, a huge price tag that can only mean fewer resources for teacher salaries, individualized instruction, new instructional technologies—and pretty much everything else that schools need and do.

Yet it’s not a foregone conclusion. Since we launched this study almost three years ago, both Wisconsin and Ohio passed pension-reform legislation that significantly brightened the economic outlook for the public school systems of Milwaukee and Cleveland. (Pennsylvania is battling over pensions as we write.) These reforms lowered the projections for 2020 retiree spending from $3,512 (without Wisconsin’s Act 10) to $1,924 per pupil in Milwaukee. Act 10 will thus save the district an estimated $1,588 per pupil in retirement costs in 2020 alone. Ohio’s SB 341 and SB 342 could save Cleveland $1,219 per pupil in 2020; not only do they lower projections from $2,476 to $1,257, but in 2020 the district will actually be spending less on retirement than it did in 2011.

Numbers like those are good for district budgets, but they exact a price. Yes, much of the debt burden was taken off the shoulders of school districts (and students), but it was placed instead on the shoulders of new, current, and retired teachers, as well as state taxpayers. This is especially vivid in Ohio, where cuts to pension benefits for new teachers may significantly reduce the desirability of a Buckeye teaching job.

Some might call this approach “eating our young,” making teaching notably less alluring for bright-eyed young instructors (and possible future teachers) while maintaining relatively generous benefits for veteran teachers and current retirees—some of whom will spend more years in retirement than they did in the classroom. Yet because of a legal environment that typically considers all public-sector pension promises, once made, to be “constitutionally protected,” policymakers have few other choices. (The exception is retiree health care, a benefit that in many states does not enjoy the same protections and thus could be a candidate for belt-tightening.) Never mind that yesterday’s “pension giveaway” becomes today’s “constitutionally protected obligation.” This is another example of how lawmakers in one year can tie the hands of their successors for decades to come.

It seems to us inevitable that, one day, public-sector employees across the United States—including but definitely not limited to educators—will find their pensions and other retirement benefits fundamentally transformed into something more like what’s now commonplace in the private sector: 401(k)-style plans that provide some assistance from employers but put much of the retirement-savings onus on employees themselves. At the very least, we’ll see a transition to cash-balance plans, which keep the government on the hook for a guaranteed payout but allow teachers to “cash out” at any time without losing their pension wealth. (Such plans also allow for greater portability than traditional state-managed retirement systems.)

But for now we’re stuck with the consequences and costs of a giant Ponzi scheme: Lawmakers have promised teachers retirement benefits that the system cannot afford, because the promises were based on short-term political considerations and willfully bad (or thoroughly incompetent) math. (For instance, assumptions about market returns that were wildly optimistic and assumptions about longevity that were overly pessimistic.) The bill is coming due and someone’s going to get soaked.

To repeat, no solution spares everybody. The best option is probably to share the pain: among retirees, current teachers, new teachers, school districts, and taxpayers.

Regarding the first two groups, without running afoul of constitutional protections, states can curtail retiree health care, as Wisconsin and Ohio did, which frees up some resources to apply to immutable pension obligations. In some states and districts (no one knows how many), governments have been picking up the tab for retirees’ health insurance between the ages of fifty-five and sixty-five (when Medicare kicks in). This benefit is practically nonexistent in the private sector, and for good reason: People in that age range are generally quite capable of paying for their own health insurance. Most are still working and participate in group plans operated by their employers.

As for filling the hole of unfunded liabilities, there’s little choice but to raise contribution rates for teachers, to increase districts’ contribution rates (which decreases funds for students) or to seek bailouts from states or the federal government (otherwise known as the “charge-it-to-taxpayers” gambit). But this is akin to putting water in a leaky bucket. Raising more revenue is necessary, but unless you attend to the leak (also known as currently accruing costs!), you’re going to have to put more and more water in. Perhaps the plug is reducing benefits, increasing age and years-of-service requirements, or decreasing retirement income via lower salary multipliers—all reasonable fixes.

A better idea? Buy a new bucket.

The unions, naturally, will scream bloody murder. It’s their job to try to hold all of their members harmless, including both current teachers and retirees. So this won’t be an easy fight.

But what should be clear from our new study is that doing nothing is not an option. Without immediate action, the problem will grow worse and districts will eventually get crushed—meaning tomorrow’s children will pay the price for yesterday’s adult irresponsibility. State lawmakers need to step up to the plate. Wisconsin and Ohio, in their ways, have at least begun to move.