Though it might be hard to believe, the first primary of the 2016 election season is still six months away. But the “ideas primary” is in full swing. Here’s what we hope to hear from candidates on both sides of the aisle. (Note to campaigns: These ideas and the related infographics are all open-source. Please steal them!)

Thank you for the opportunity to speak about the number-one domestic issue facing our country today: How to improve our schools so that every child has an opportunity to use their God-given talents to the max, contribute to society, and live the American Dream.

In a few minutes, I’m going to talk about what’s wrong with our education system. That’s appropriate, because bad schools continue to steal opportunities away from too many of our young people.

But before we get to that, how about some good news for a change? American schools, on the whole, are getting better. A lot better. Test scores are up—especially in math, and especially for our lowest-performing, low-income, and minority children. Graduation rates are at all-time highs. The college completion rate is inching upward. Things are heading in the right direction.

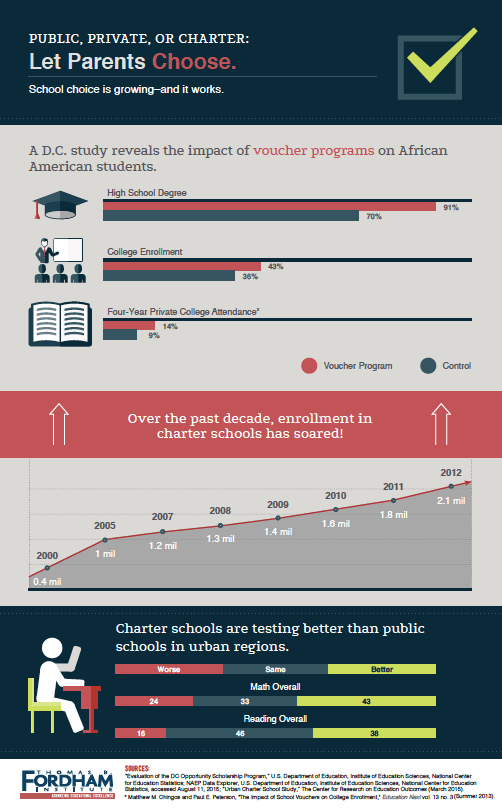

Why are things getting better? Because of two decades of education reform. Greater parental choice. An explosion of charter schools. More accountability for results. Higher standards. Better teaching.

To be clear, we have a long, long way to go. Progress has not been nearly fast or widespread enough.

But let’s acknowledge that progress is possible. The naysayers don’t think we can set things right, and they justify mediocrity by saying our schools are doing the best they can under the circumstances. We know better. We know we can do better. And our teachers and leaders deserve credit for the hard work that’s gotten us this far.

***

So we’ve made progress. But that has meant making changes and those changes haven’t always been popular. Real change never is. But more progress will mean more changes ahead. This is especially true when it comes to the education of our most disadvantaged children: those growing up in poverty, in single-parent homes, and in dangerous neighborhoods.

There’s been a lot of talk about whether the American Dream is still alive, and whether kids who grow up poor today still have a shot at making it. Many of us have our own American Dream story, of parents or grandparents or aunts or uncles who grew up poor, but worked hard in school and used a sound education to climb the ladder of opportunity.

Is that still possible today? Absolutely. But it’s tough. Good jobs now require high-level skills. And that almost always means some sort of education or training beyond high school.

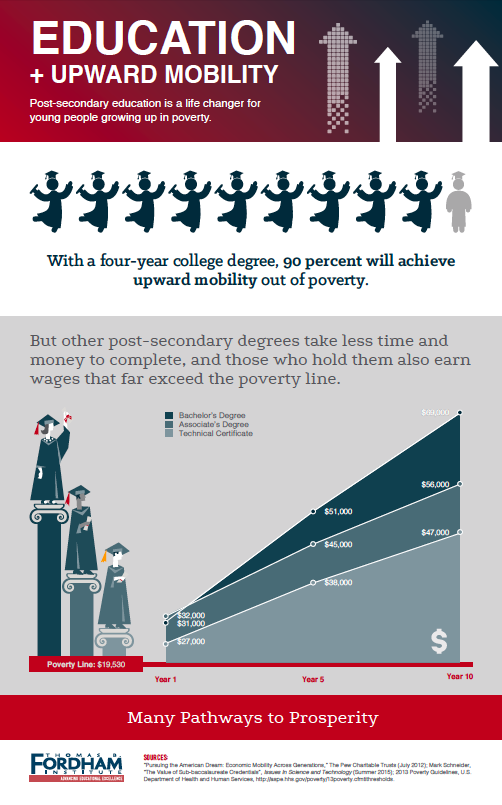

Four-year college degrees are still best. For kids growing up in poverty, graduating from college is practically a guarantee that they will be free from it, and that their kids won’t know the hardship they did. Ninety percent of poor kids who graduate with a four-year college degree make it out of poverty.

That’s the good news. The bad news is that only about one poor kid in ten is making it to that degree. That’s not nearly enough. That’s why we can’t listen to the naysayers who want to stop making changes. We have to keep going, faster and smarter. We have to continue to raise expectations for our elementary and high schools so that many more kids are ready for college. And we have to continue to expand parental choice and grow the number of high-quality charter schools—the kind getting twice, three times, four times, five times the number of low-income students to and through college.

We also have to broaden our focus beyond the four-year college degree. Two-year technical degrees, and even one-year credentials, can also propel poor children into the middle class, especially if they choose the right field.

But expanding those options will also require changes, because too many places have given up on vocational education. High-quality career and technical education needs to be a viable option for many more kids, beginning in high school. It shouldn’t be forced on anyone, but it has to exist as an option for those who want it. Put teenagers on a path to meaningful credentials. Give them experience in a real workplace. Offer them apprenticeships. Find them great mentors and role models. Show them what it means to work.

So we must do more, a lot more, for our poorest and lowest-performing children. But they aren’t the only ones whose needs aren’t being met, and they shouldn’t be the only ones whose needs count.

All over this country, talented students don’t reach their potential because when they get to school, we tell them that they aren’t a priority. They can pass the standardized tests with their eyes closed, so we tell high-ability kids that their job is to sit still and stay quiet while the teacher focuses on low-achievers.

How is that fair? Everyone deserves to come to school and learn something new every day. Everyone deserves the chance to go as far and as fast as their ability allows. And yet our school system too often puts barriers in front of high-achievers. Rather than opening up programs and opportunities for gifted students, our schools shut them down.

This is most damaging for the life prospects of high-ability kids from poor families, who have perhaps the best shot at using a strong education to make it to the middle class. Yet in their schools especially we’ve eliminated the gifted programs, closing off their chance to excel. We’ve said to our young strivers, “You’re on your own.” That’s not right.

Something similar is going on when it comes to school discipline. Thankfully, our schools are safer and more orderly than ever. But that wasn’t always so. I can remember a time, not long ago, when many of our schools were wracked by constant fighting, disrespect for teachers, and general unruliness. But over the course of many years, most American schools reestablished discipline standards and found more effective ways of establishing positive school cultures. And students responded.

But now some want to walk away from all of that. They want to tie schools’ hands and make it harder to discipline disruptive students. They are worried that we are suspending and expelling too many kids. Some schools surely are, and that should be fixed. But just as “active policing” has made our cities dramatically safer, more vigorous discipline policies have done the same for our schools. Those gains are too valuable to walk away from. And the federal government should stop trying to make us forfeit them.

If our schools become less safe and less orderly, who will suffer? That’s easy: the vast majority of students who are behaving, working hard, and doing their best to learn. Especially the good kids in the toughest schools.

Let me finish with one last thought. I’ve saved the best for last.

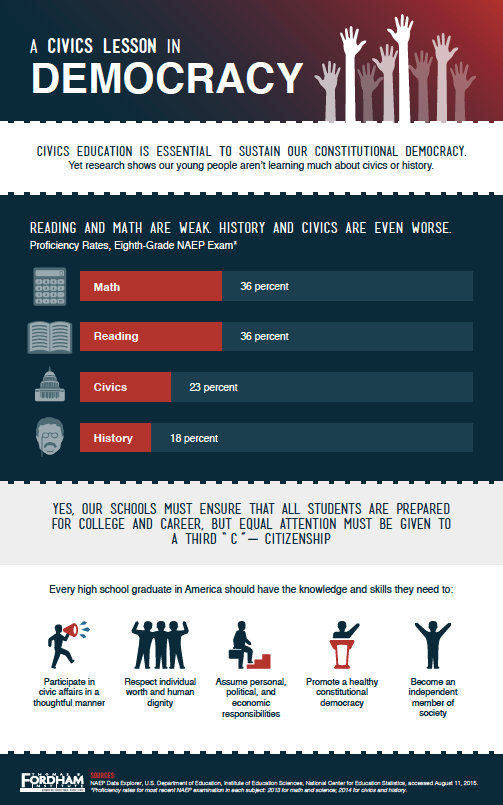

We are here today participating in a wonderful American democratic tradition: running for president, meeting the voters, and debating the issues. And if there’s one thing our schools must accomplish, it’s to make sure that all of our young people are ready to participate fully in our democratic life. And yet that civic mission of the schools is often an afterthought. We are so focused on preparing students for college or career that we forget the third C: citizenship.

I promise you, I won’t forget. I will shine a light on those schools that are inspiring their students to learn and practice the habits of citizenship.

***

So let me recap. When it comes to education reform, we’re making progress. But we need to go faster. Nothing is more central to the cause of reviving the American Dream. And we need to go broader. Raising student achievement, boosting high school graduation and college completion rates, re-envisioning vocational education to equip our kids for twenty-first-century jobs—all of that matters immensely. But so does nurturing the talent of our most gifted students, ensuring an orderly place for all children to learn, and achieving the civic mission of our schools.

Let’s get to it. Let’s keep at it. Let’s not stop until this important work is done.