The Akron Beacon Journal recently reported on the struggles of Next Frontier Academy, a charter school whose failures have included incomplete student records, missing funds, inflated enrollment figures, an inability to make payroll and rent, and student-on-student (and student-on-staff) violence that went unreported to the police. This type of educational malpractice ought to make everyone angry—especially charter school supporters and allies. Mercifully—for its forty students and Ohio’s taxpayers alike—the school closed this summer.

The closure isn’t an anomaly in the Buckeye State. Since the charter school movement’s inception in 1997, over two hundred schools have shut their doors. According to the Beacon Journal, “more charter schools closed last year than at any point in the industry’s seventeen-year history in Ohio.”

Closure isn’t necessarily a terrible thing. It certainly isn’t proof that the movement has failed, as some critics suggest. Charter schools that are under-enrolled, financially unstable, or academically deficient should be closed. This feature sets them apart from traditional public schools that stay open forever regardless of performance, and it should be embraced. Moreover, evidence suggests that students are the winners when low-performing schools are closed, despite the initial disruption and inconvenience that may occur. A Fordham study from earlier this year showed that students made significant gains in both math and reading after their schools closed.

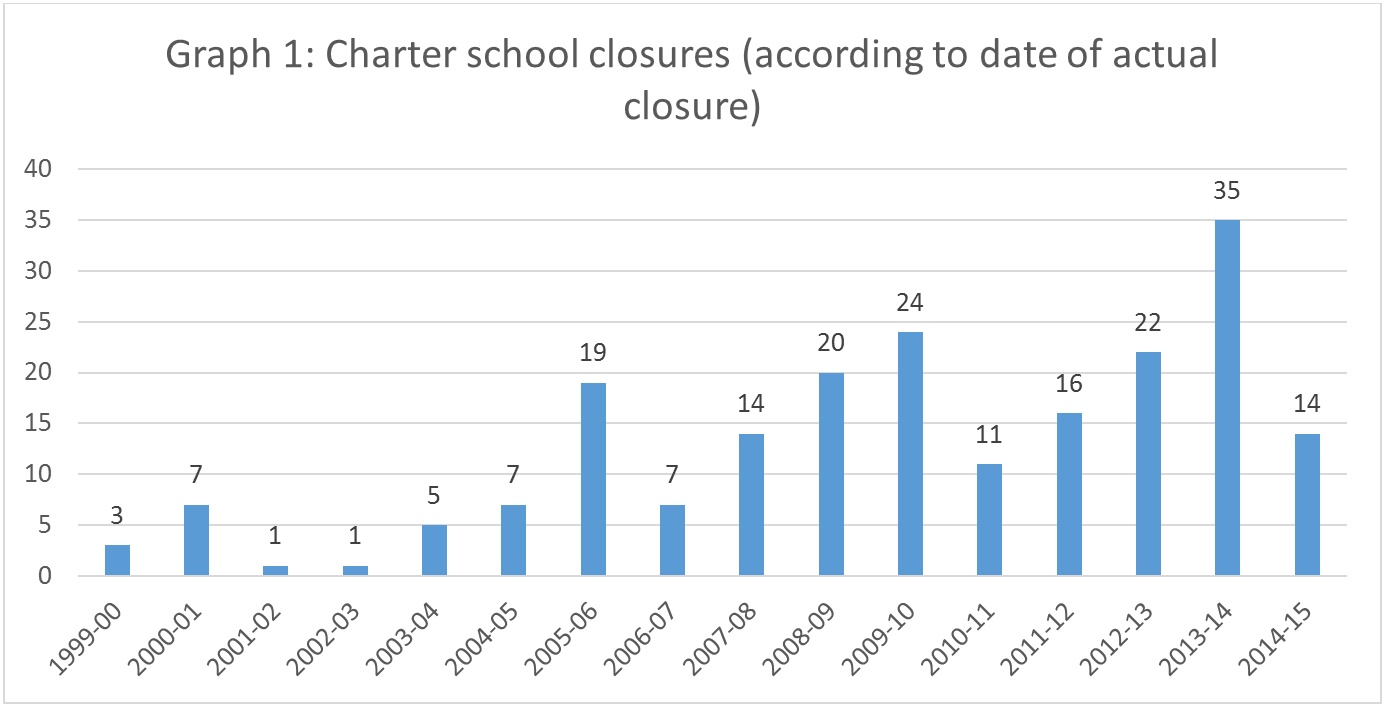

Still, widespread closures are alarming and deserve further exploration. Data from the Ohio Department of Education[i] confirms that the 2013–14 school year (the most recent one for which complete data are available) set an unsightly record: Thirty-five charter schools closed up shop. By our count, this means that 17 percent of all closures in the movement’s history occurred in a single year.

Ohio has an automatic closure law that requires charter schools to shut down if they chronically underperform. Further, the state has ramped up efforts to hold charter school sponsors (a.k.a. authorizers) accountable for their schools’ academics. It therefore makes sense that Ohio is experiencing higher numbers of closure during the more recent years of the movement’s history (as depicted by Graph 1). While thirty-five closures in one year is somewhat shocking, the trend laid out in Graph 1 overall is not.

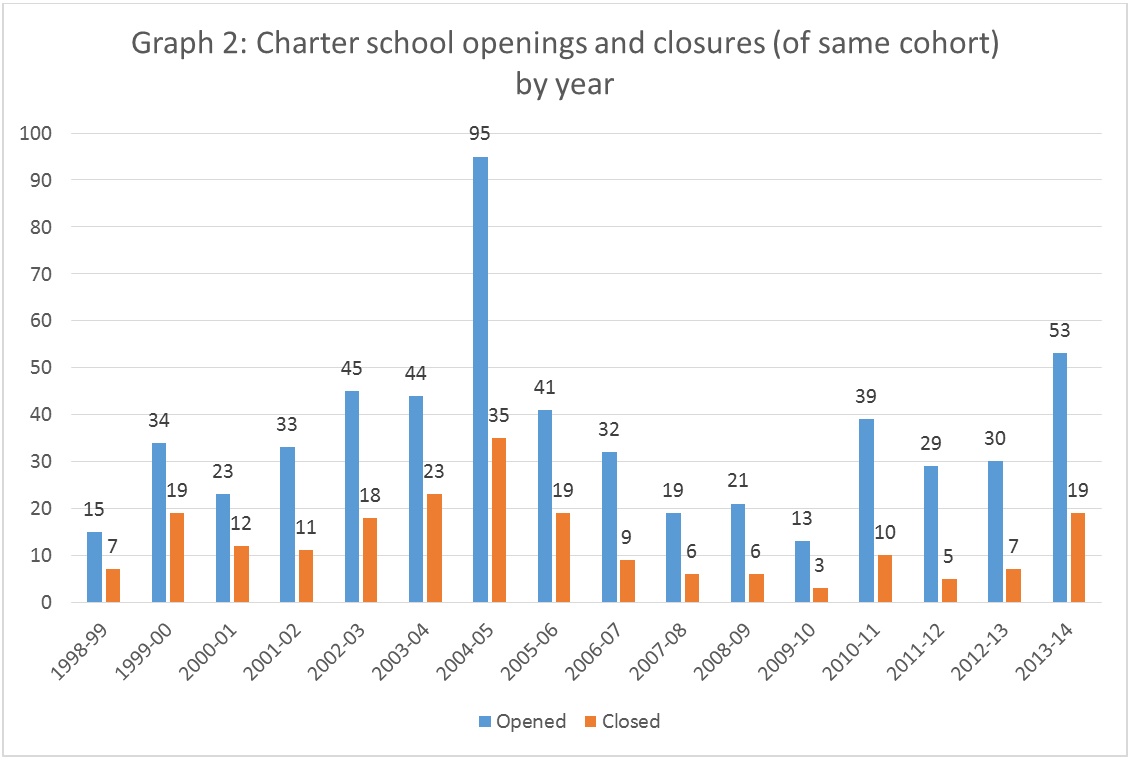

Graph 2 (below) attempts to shed light on the closure rates of charter schools based on the year they opened. In other words, of all schools that opened in a given year, how many have closed—regardless of what year in which the closure took place? Examining school openings and closures by yearly cohort adds context. Which years experienced the highest rates of opening, or the highest rates of closure? How successful was each group of start-up charter schools (with success being defined narrowly as the ability to remain open)?

For example, three schools that opened in 2009–10 ended up closing, but only thirteen in total opened that year—an overall success rate of 77 percent. 2011–12 had the highest success rate (83 percent): Twenty-four of the twenty-nine schools started that year remain open today. Conversely, only 44 percent of schools started in the 1999–00 school year are still around, but those nineteen schools may have closed at any point in the last fifteen years.

In contrast, nineteen start-ups from the 2013–14 school year alone have already closed. And that’s based on data that only provides information up to 2014. Once 2015 information is added in, that number will likely be higher.

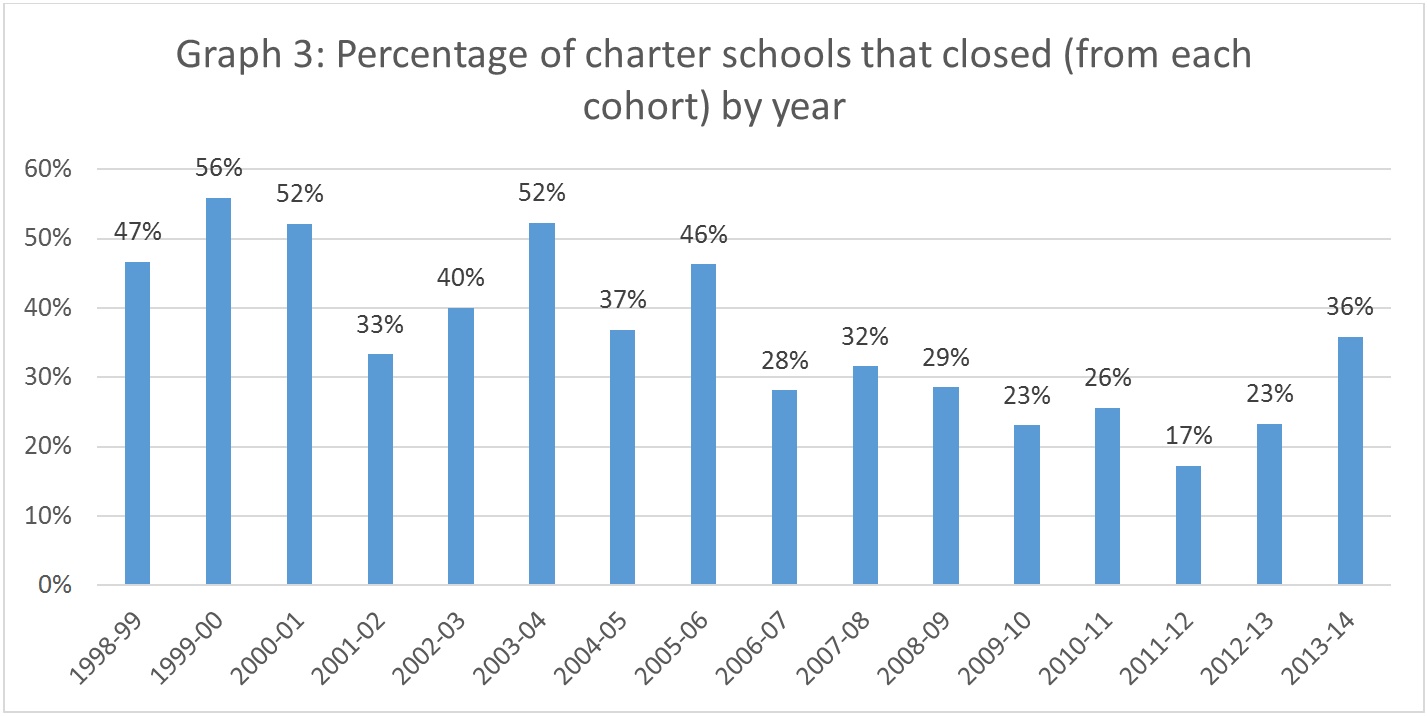

Graph 3 shows the closure rates of charter schools by yearly cohort, with 2013–14’s group of start-ups experiencing the highest closure rate in nearly a decade (36 percent).

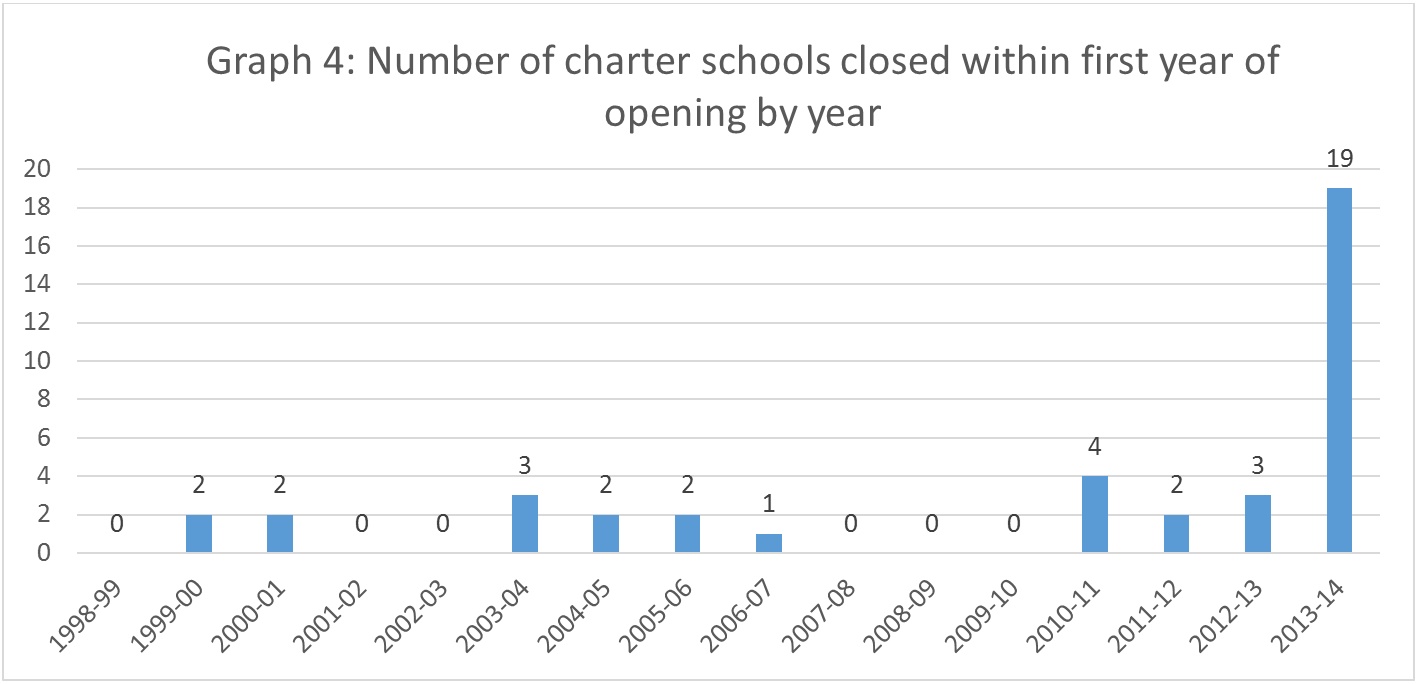

Graph 4 illustrates just how radical 2013–14 was, with an unprecedented number of first-year start-up failures. Nineteen schools that opened in 2013-14 were closed mid-year or by the conclusion of that school year, five times as many first-year failures as Ohio had ever witnessed.

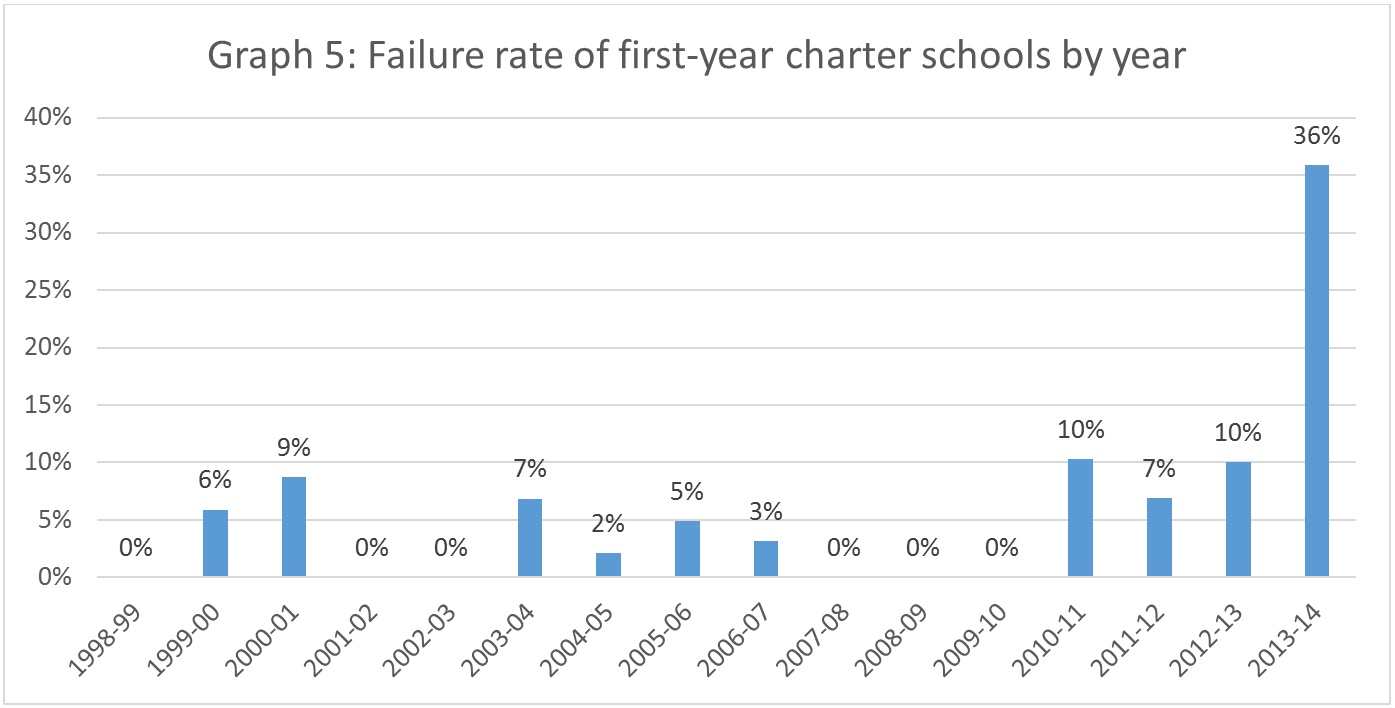

Graph 5 tells the same story: As a percentage, 2013–14 far surpassed all others in its overall failure rate of first-year charter schools.

Some might argue that widespread closures are proof that charter school overseers—governing boards and sponsors—are doing their jobs. Don’t the relatively high number of closures from 2013, 2014, and 2015 (Graph 1) illustrate that Ohio’s emphasis on quality oversight is working?

Partially, yes. The vast majority of closures (all but twenty-four) in the past decade and a half were “voluntary” or “sponsor-ordered” rather than triggered by the automatic closure law. Governing boards and sponsors are deciding to shut down charter schools that are no longer academically effective or financially viable, as they should. Closing a charter school is no easy task as the Fordham Foundation’s authorizing department can attest. So kudos to anyone who has played a role in closing an ineffective school.

But as Graphs 2, 3, 4 and 5 illustrate, quality oversight is not in place in all phases of a charter school’s life cycle. Widespread failure like what occurred from 2013–14 points to a glaring problem with how sponsors vet and open new schools. That’s an equally (if not more) important component of oversight. A sponsor is the gatekeeper of quality at its school’s inception. It conducts due diligence on new school applicants, examines their track records (and, one hopes, their criminal records and bank accounts), and uses value judgments regarding which schools it thinks will ultimately succeed or fail.

We must expect more from these gatekeepers. Closing poor performers when they have no legs left to stand on is only a small part of effective oversight. A far better alternative would be to prevent them from opening in the first place. Sponsors don’t have to be soothsayers to predict failure where prospective applicants have failed before, or where they lack the funds or expertise to run a school. The bottom line is that when a closure happens in the first year or two of operations, there were usually warning signs; if heeded, those signs should have kept the school from ever opening. If Ohio charter schools are going to improve, better decision making about new school applicants will be critical.

After a record-breaking year for closures and public debacles on the sponsoring front, Governor Kasich and the Ohio House and Senate have come to the same conclusion. This past spring, sponsor accountability was a centerpiece in each of their respective charter school reform plans. House Bill 2 puts in place several reforms to reward high-performing sponsors and minimize perverse incentives embedded in the current system. If passed, HB 2 would only allow quality sponsors to open new schools. The bill also prohibits sponsors from selling services to the schools they oversee and places strict parameters around schools wishing to find a new sponsor.

Sometimes sponsors will get it wrong, and that’s okay. By nature, charters were designed to offer innovative alternatives, and Ohio can’t spur innovation unless it’s willing to tolerate some degree of risk. The state recently won a federal Charter School Program (CSP) grant that will inject $71 million into the sector. Ohio should use this money to help excellent schools replicate and recruit high-performers. The reforms in HB 2 are necessary to ensure that we manage the risk of opening new schools much better than we have in the past, a responsibility—and opportunity—that is amplified by the infusion of CSP funds. Never again should nineteen schools start and stop within the same year. As a sector, we can and must do better.