Ohio needs to fix its method for counting and funding low-income students

This is second in a series where I examine issues in K–12 education that Ohio leaders should tackle in the next biennial state budget.

This is second in a series where I examine issues in K–12 education that Ohio leaders should tackle in the next biennial state budget.

This is second in a series where I examine issues in K–12 education that Ohio leaders should tackle in the next biennial state budget. The first covered the state’s science of reading initiative, and this essay looks at the way Ohio counts—and funds—low-income students.

Everyone today agrees that low-income students tend to need more resources to achieve rigorous standards and exit high school ready for college or career. Such students usually come from more challenging backgrounds and face obstacles that—without strong supports—can lead to achievement gaps. Teaches also tend to demand a salary premium to serve in high-poverty schools, which is another reason to provide extra dollars.

In line with this thinking, Ohio has long provided additional funds to needier schools. This academic year, Ohio will allocate $563 million in Disadvantaged Pupil Impact Aid (DPIA)—one of the components of the overall school funding formula. These dollars are intended to cover the costs of providing supplemental services, such as high-dosage tutoring, extended learning time, and other interventions.

Additional funds for low-income students remain essential to the state funding system, but lawmakers must improve the way dollars are steered to districts and charter schools. The underlying problem is that Ohio misidentifies thousands of higher-income students as “economically disadvantaged,” which in turn thins the dollars available to support students who are actually low-income. Fortunately, as discussed below, there is a solution—“direct certification”—that would improve the accuracy of these data and better ensure that funding goes to support students who need it the most.

Problems identifying “economically disadvantaged” students

Along with several other states, Ohio uses a students’ eligibility for federally subsidized meals to identify them as economically disadvantaged. In the past, this method worked out reasonably well. Eligibility for free-or-reduced-priced lunches was restricted to students from households earning less than 185 percent of the federal poverty level.[1] Hence, disadvantaged numbers used to more accurately reflect students who were low-income.

Congress, however, relaxed eligibility requirements in 2010 by enacting the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP). This policy allows qualifying[2] mid- to high-poverty districts and individual schools to provide subsidized meals to all students—regardless of their family income. While this has reduced the administrative burden of verifying incomes and perhaps improved child nutrition, CEP has eroded the quality of economically disadvantaged data in states like Ohio.

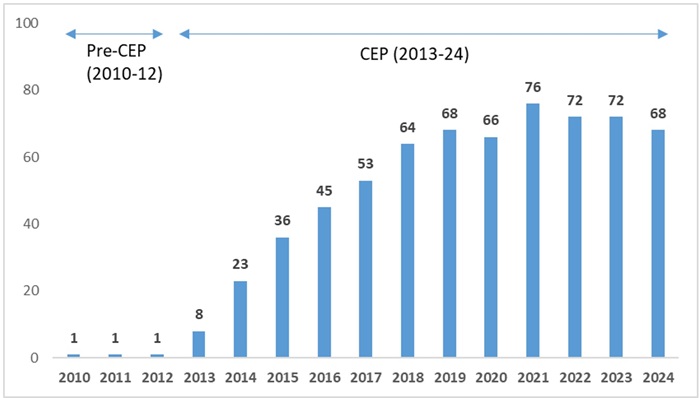

Figure 1 displays the marked increase in the number of districts reporting universal to near-universal disadvantaged rates after the introduction of CEP. Prior to 2012–13, the first year of program implementation in Ohio, just one district (Cleveland) reported all students as disadvantaged. With CEP, that number began to rise and since 2017–18, more than sixty districts—roughly one in ten—have reported rates above 95 percent.

Figure 1: Number of Ohio districts reporting 95 percent or more students as economically disadvantaged

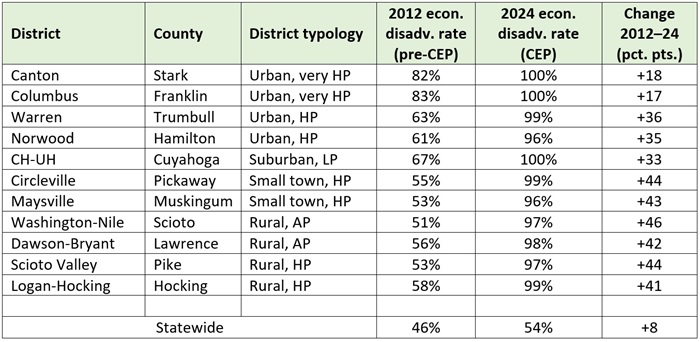

As the table below indicates, many of the districts that report universal rates today had nowhere near those numbers prior to CEP. Circleville, for example, had a disadvantaged rate of 55 percent in 2011–12. This year, the district reports nearly every single student as disadvantaged. As shown at the bottom of the table, the statewide disadvantaged rate has also climbed. Note that an actual increase in low-income students cannot explain these jumps, as Census data indicate a slightly declining childhood poverty rate for Ohio over the past decade. Instead, today’s sky-high disadvantaged rates reflect the impact of CEP.

Table 1: CEP districts reporting the largest changes in disadvantaged rates in each district typology

Inflated disadvantaged rates lead to unfair allocations of state aid

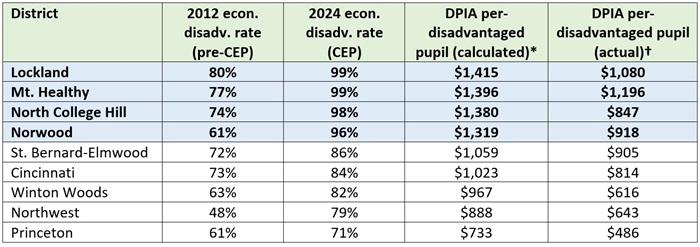

Because DPIA funding is tied to disadvantaged rates, CEP districts reap windfalls while similarly situated non-CEP districts receive substantially less. Table 2 shows stark differences in per-pupil DPIA funds for CEP districts in Hamilton County versus other districts that likely have similar numbers of disadvantaged students. As the fourth column indicates, the four CEP districts receive more than $1,300 per disadvantaged pupil under a fully phased-in formula—far more than their non-CEP peers.[3] Column five indicates that two of the CEP districts receive more than $1,000 this year under the actual “phased-in” formula. These amounts are considerably higher than what non-CEP districts receive, even though they’re also high poverty. Cincinnati, for instance, receives approximately 20–25 percent less per disadvantaged pupil than Lockland and Mount Healthy. Princeton receives roughly half of what Norwood receives in DPIA, despite historically having an almost identical disadvantaged rate.

Table 2: DPIA funding for selected districts in Hamilton County (CEP districts shaded in blue)

Toward more accurate headcounts and a fairer allocation of DPIA

To ensure accurate data on disadvantaged students and to improve the allocation of DPIA, lawmakers should make two changes.

First, they should require the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce (DEW) to identify low-income students based on direct certification. Rather than counting students based on meals eligibility, this process identifies low-income students through a records match with their families’ participation in programs such as SNAP, TANF, or Medicaid.[4] Tennessee and Massachusetts have moved to using direct certification to count low-income students, and this process is already used in Ohio to determine districts’ and individual schools’ eligibility for CEP. By removing higher-income students from Ohio’s disadvantaged headcounts, direct certification would yield more reliable data on low-income students.[5]

Second, lawmakers should then use these more accurate data to drive DPIA funding to schools. While fewer students would be identified as economically disadvantaged under direct certification, it would allocate dollars more fairly to districts. Moreover, with fewer disadvantaged students identified and more confidence in the data quality, Ohio could (and should) boost the per-pupil DPIA funding so that low-income students receive even stronger supports.

Properly funding low-income students’ educations should remain a priority for state lawmakers. Yet without a reliable method for identifying them, Ohio is misdirecting millions in funds. The state’s current funding formula is often hailed by supporters as the “Fair School Funding Plan.” To live up to that impressive billing, lawmakers must shift to a more accurate count of low-income students.

[2] Until recently, to qualify for CEP, districts and schools had to identify at least 40 percent of students as low-income through direct certification—a process in which students are certified as low-income based on their families’ participation in SNAP, TANF, or other means-tested programs. Starting in October 2023, the federal government lowered the threshold to qualify for CEP to 25 percent of students direct certified. This could further increase the number of CEP districts and schools in Ohio.

[3] Some of the non-CEP districts are likely to have individual schools that participate in CEP (e.g., Cincinnati).

[4] Other flags that indicate disadvantagement such as a homelessness or foster status could also be included.

[5] More accurate identification of disadvantaged students would also strengthen research that seeks to study the impacts of policies and programs on low-income students, as well as accountability systems that aim to hold schools accountable for the academic outcomes of disadvantaged pupils.

Last year, state policymakers unveiled a bold plan to improve early literacy in Ohio. The centerpiece of that plan is the science of reading, a research-based instructional approach that emphasizes phonics and knowledge building.

Given the intense focus on what’s new and different about these reforms, one might assume that Ohio’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee—passed more than a decade ago—is a thing of the past. But that’s not the case. The guarantee’s controversial retention requirement was unfortunately watered down, but many of its other provisions remain in place. One such provision requires districts and charter schools that meet certain criteria to submit a Reading Achievement Plan (RAP) to the state. As the name suggests, a RAP focuses on student achievement in reading, and must include analyses of student data and measurable performance goals.

Last year, the Department of Education and Workforce (DEW) released a list of districts and charter schools that were required to submit a new RAP to the state by December 31. As of this writing, DEW’s website also contains RAPs from the 2018–19 school year. Quite a bit happened between 2018 and 2023, namely a once-in-a-generation pandemic that had massive impacts on student achievement. But that’s exactly why comparing a district’s 2018 RAP to its updated 2023 plan is a useful exercise for state leaders. In each plan, districts and schools were required to identify any internal or external factors that they believed contributed to underachievement in reading. Factors that persisted through—or worsened during—the pandemic should be considered potential threats to Ohio’s latest early literacy initiative.

Several districts were required to submit RAPs in both 2018 and 2023, but this piece will compare the plans submitted by just one of them: Columbus City Schools (CCS). Columbus is an ideal case study, as it’s the largest district in the state and has a history of troublingly low reading achievement. In short, contributing factors that are consistent in Columbus over time are likely present elsewhere. Although these plans contain plenty of more obvious reading-related issues to consider, here are three significant concerns that policymakers should keep an eye on going forward.

1. Chronic absenteeism

In both the 2018 and 2023 plans, CCS identified chronic absenteeism—defined by the state as missing at least 10 percent of instructional time for any reason—as a factor contributing to underachievement in literacy. Given the well-known and far-reaching negative impacts of chronic absenteeism, it’s a no-brainer for district officials to flag it as a key problem. But it’s also important to recognize just how alarmingly high the district’s chronic absenteeism rates are in the earliest grade levels.

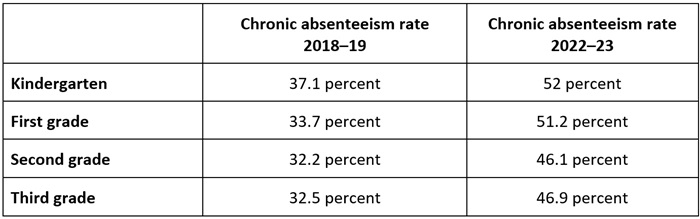

Table 1: Chronic absenteeism rates of Columbus City School students in grades K–3

Table 1 indicates that chronic absenteeism rates in Columbus were high prior to the pandemic—a third or more of students in grades K–3 met the state’s identification threshold—and are even higher in the wake of it. With roughly half of all elementary students missing a significant amount of school, it’s no wonder that just 35 percent of Columbus third graders were proficient in reading last year.

Student attendance woes aren’t unique to Columbus. Hundreds of districts across the state are also struggling with chronic absenteeism rates that shot up during the pandemic and have yet to come back down, and absenteeism has long been particularly problematic for the youngest and oldest students. If state policymakers are serious about improving early literacy in Columbus (and hundreds of other districts in the same boat), they must improve student attendance as a bedrock principle. That means supporting innovative incentive ideas to get kids to attend school. It means holding adults—the staff responsible for making schools the kinds of places kids want to be, and the parents responsible for ensuring kids get there—accountable. Most importantly, it means continuing to transparently track student attendance, resisting efforts to make it easier for kids to miss school, and ensuring that school calendar laws send the right message about the importance of consistent attendance.

2. Teacher shortages

Both plans reference staffing shortages, particularly in regard to substitutes, as another factor that contributed to underachievement. The 2018 plan notes that a “consistent lack of qualified substitutes” contributed to the district’s “inability to access teachers and provide ongoing and intensive professional development.” The 2023 plan also mentions substitute teachers, claiming that during the three most recent school years, there were “inconsistencies in classroom instruction due to the lack of substitute coverage.” The most recent plan also mentions broader teacher shortages that extend beyond subs. Because of these shortages, district officials say, many PreK–5 teachers “have been forced to teach outside their areas of expertise and/or with larger class sizes.”

As was the case with chronic absenteeism, Columbus is not the only district grappling with staffing issues. The good news is that after years of declines, enrollment in Ohio’s teacher preparation programs is trending upward. Also in the good news column are state initiatives like a teacher apprenticeship program, a grow your own teacher scholarship, and policy tweaks aimed at expanding the pool of substitute teachers. These initiatives should help bolster the teacher pipeline from the largest district on down.

But that doesn’t mean state leaders can rest on their laurels. It’s crucial to get right the teacher preparation audits that were included in the literacy reform package. If not, we run the risk that an otherwise welcome influx of new teachers will turn into a nightmare because they lack proper training. To avoid this pitfall in districts large and small, lawmakers will need to allocate more funding for audits in the upcoming state budget and stand strong against likely pushback from higher education.

3. Professional development

In last year’s state budget, lawmakers allocated considerable sums toward helping current teachers understand and implement the science of reading. Over the next biennium, $86 million will go toward professional development. Another $18 million will pay for literacy coaches, who will be charged with providing intensive support to teachers in the state’s lowest performing schools.

If this state investment had occurred in 2018, CCS officials likely would have been thrilled. That’s because, in their 2018 RAP, they identified professional development as a factor contributing to their underachievement. Beyond the substitute teacher issues outlined above, the plan also notes that the district needs to “further define the role of instructional coaches related to literacy,” as well as “identify a mechanism for ongoing instructional support for teachers to ensure effective implementation of high impact reading instructional strategies.”

Given these stated aims, one might think that the district’s 2023 plan would have good news on the professional development front. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. The 2023 plan notes that, although the district has provided “multiple opportunities” for teachers to receive professional development related to new curriculum resources for literacy, “many teachers have failed to complete training due to professional development being outside the contractual workday.”

The good news for Columbus leaders is that professional development in reading science is no longer optional. The state budget requires teachers and administrators to complete a professional development course in the science of reading. The state also addressed concerns about teachers working outside contractual work hours by offering stipends of up to $1,200 to those who complete the course.

For state leaders, on the other hand, professional development struggles in Ohio’s largest district should serve as a warning sign. Even with mandates and stipends in place, getting every teacher on board with the science of reading will take unwavering commitment—something that hasn’t historically described Ohio lawmakers. State leaders may also need to provide more funding in the upcoming budget to cover the cost of curriculum-specific training, additional literacy coaches, and other types of support.

***

These aren’t the only potential pitfalls facing Ohio on its road toward improved reading achievement, but they are big and noteworthy. Their existence in both the 2018 and 2023 Columbus RAPs indicates they are persistent. And if they’re happening in the state’s largest district, many other districts are likely experiencing their own version of the same. Going forward, state and local leaders must do everything in their power to proactively address these issues. Otherwise, the science of reading push could founder.

“Teaching to the test” is a common pejorative term that touches on a number of hot-button education policy issues—top-down mandates to schools, shrinking curriculum, hamstringing teacher autonomy and creativity, and dampening student interest in learning to name just a few. A new report from Austria puts those negative implications under the microscope and, despite limitations of the methodology, finds some valuable insights from the field.

The context is a change in the structure of school-leaving exams in mathematics, which are required of all Austrian students prior to high school graduation. Traditionally, the tests were designed by the teacher of the final class in each school. Although there were minimal design strictures, each exam was required to consist of four to six tasks to be solved independently of one another. Tasks had to include calculation exercises, argumentation, representation, interpretation, and “the application of mathematics in non-mathematical areas.” Students were allowed only a calculator, a formula booklet, and a normal distribution table as aids. Proposed exam tasks were sent to the local education authority for approval before administration, but were rarely challenged. As a result, every classroom of seniors took a different exam every year, with minimal comparability even within the same school building.

In 2014, following nationwide calls for a common test that would reduce subjectivity, allow for comparability, and ensure students had acquired basic mathematical competencies, schools began administering the standardized school leaving exam (SSLE). The SSLE format has changed a bit over the years, but today it covers four general content areas—algebra and geometry, functional dependences, analysis, and probability and statistics—with standalone and inter-related problem sets created annually by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Science, and Research. In addition to the goals listed above, more emphasis was placed on student aptitude with technology, and so they are allowed to use higher level technological aids (such as GeoGebra and graphing calculators) without restriction during testing.

Data on teachers’ experience of the testing change come from interviews with ten upper secondary math teachers who had significant teaching experience covering both the teacher-created and standardized exam eras. They were conducted from March to May of 2023. This is obviously a very small subset of all math teachers in Austria, and all of them volunteered to participate in the questionnaires, but even the limited anecdotal evidence obtained is valuable.

Teachers almost universally viewed the goal of standardization as positive, and reported that they believed that the competencies emphasized by the SSLE are valuable to students. They were less positive, however, regarding what they view as a change in their roles from a traditional instructor to more of a “trainer” who pursues a common goal with the students—as if they all needed to work together to pass somebody else’s test. All teachers felt that they needed to focus the curriculum they covered in class on those areas to be tested, thereby “teaching to the test.” Whether they were able to include more concepts depended on how long the SSLE material took. Two teachers noted with some dissatisfaction that they regularly needed to justify to their students any time spent on non-SSLE content. A majority of teachers reported ditching most or all of the official textbook in favor of old SSLE problem sets, and using the advanced technological aids at least weekly after the switchover to the new test. While some teachers expressed negativity about the loss of technology-free teaching, others reported working without the aids at first to build competency and then introducing them later as test time approached.

A majority of teachers reported increased cooperation with one another after SSLE was introduced, especially within schools. This likely reflected the fact that creating individual tests was no longer required, and every math teacher now had to equip their students to pass the same test. Interestingly, the new comparability of scores led to some teacher-reported competition between schools. Teacher satisfaction with SSLE—and all the changes the test has wrought—has increased in the years since it was introduced, reflecting both a growing familiarity in and comfort with what is required, and (in a few cases) resignation that the old-school exams aren’t ever coming back. Some ongoing logistical issues as reported by individual teachers include continual tweaks in aspects of the SSLE (more are scheduled between now and 2030), inconsistent and short-notice communication about changes to the exam, and a perceived lowering of rigor in some aspects of exam questions and tasks.

The scope of this survey data is small and limited, but feels useful all the same. There’s no denying that the switch to a standardized test resulted in a shrinkage of the core curriculum and an increase in “teaching to the test” in most math classrooms in Austria. But there appears to be no organized effort to remove SSLE after nearly ten years, and predictable negative responses to the change, often stated loudly and preemptively in other places, were muted here by several important factors.

First, a majority of teachers surveyed understood and accepted the goals of the standardized exam even before it was implemented, and saw them as positive for students. SSLE was, in fact, a test worth teaching to. Second, many teachers found ways to exercise their own autonomy and creativity while the official curriculum contracted—even if it took a few years to learn the ins-and-outs of SSLE before they could do so. Third, the increase in cooperation that arose among math teachers who had previously been systematically siloed was seen as a positive outcome despite any lingering concerns they may have had about the testing changes.

This is a small subset of teachers; surely there were many with other viewpoints. But the fact that these few tolerated the switch and found numerous positive aspects feels like proof that more could manage it with enough buy-in, support, and concrete evidence showing that “teaching to the test” isn’t the end of the world.

SOURCE: Christoph Ableitinger and Johanna Gruber, “Standardized school-leaving exam in mathematics: manifold effects on teaching, teacher cooperation and satisfaction,” Frontiers of Education (March 2024).

The use of technology in education—in place before the pandemic but increased in magnitude and ubiquity since 2020—is drawing increasing scrutiny from many sides. The villagers are lighting up their torches and coming en masse for cellphones, online learning platforms, Chromebook-based assignments, Smartboards, and more. A trio of researchers from the University of Michigan suggest another log to stack on the pyre: electronic grade books. Their new research shows, among other things, how even the bedrock of the English alphabet can be weaponized when brought in contact with the white heat of technology.

Specifically, the researchers look at more than 31 million grading records submitted to a learning management system called Canvas by graders from an anonymous large public university in the United States between 2014 and 2022. Canvas is the most popular system of its type, in use at 32 percent of all higher education institutions in the United States and Canada in 2020. To avoid biasing the analysis, the researchers include only human-graded assignments, removing assignments and courses that have either massive numbers of grades or an extremely small number of grades, as well as assignments graded offline and only submitted electronically. The final data set still contains a whopping 31,048,479 electronic grades covering 851,582 assignments, 139,425 students, and 21,119 graders. Data include both numerical values and textual values (comments from the grader). Timestamps allow the researchers to determine both the order in which assignments are submitted and in which they are graded. Additionally, the Canvas platform includes any comments entered by students in response to the grades after they are made available.

The bedrock finding is that electronic grading of student work appears to be a slog for most humans cursed with the task, and that using a system like Canvas—designed to ease the burden—only compounds the problems. This analysis indicates that negative impacts of electronic grading can accrue to specific individuals as a matter of course. Students whose assignments were graded later in the process—however that process was sequenced—received lower marks and more negative comments than their peers. Surname alphabetical order grading, the default setting for Canvas and comprising over 40 percent of the submissions analyzed, tells the tale clearly. Students whose surnames started with A, B, C, D, or E received a 0.3-point higher grade (out of 100) than did students with surnames later in the alphabet. Likewise, students with surnames W through Z received a 0.3-point lower grade than their earlier-in-the-alphabet peers—creating a 0.6-point gap between the Abdullahis and the Zimmermans of the world. Robustness checks among different graders, including a small group (about 5 percent) who happened to have graded in reverse alphabetical order and exhibited the same gap, confirmed this pattern. That might seem a small difference, but if it happens to the same students on every assignment in multiple classes over multiple years, the small gap could grow into a much larger one.

Grader comments on assignments evaluated later in the sequence were found to be more negative and less polite (the handful of examples included in the report would be truly disheartening for their unfortunate recipients) than those given earlier in the sequence. Grading quality seemed to deteriorate down the sequence, as well. Students with assignments graded later were significantly more likely to log questions and challenges about their marks in Canvas. Specifically, students graded between fiftieth and sixtieth in order are five times more likely to submit a regrade request compared with the first ten students graded, no matter in what order the grading is done.

While the surname alphabetical grading order illustrates sequential bias most clearly and sensationally, the same pattern was also observed across assignments graded in quasi-random order. The more assignments that must be graded, the more likely students at the end of the sequence are to be impacted. And in the case of learning management technology, that largely means students whose surnames are late in the alphabet. As noted, Canvas (and its three closest competitors) defaults to alphabetical order and must be manually changed by graders or institutions to avoid this. Together, these four systems accounted for over 90 percent of the U.S. and Canadian market at the end of 2020, so the potential negative impact to the Whites, the Williamses, and the Youngs is huge.

The researchers end with three commonsense recommendations. First, creators of learning management systems should switch their products’ default from alphabetical to random order (with educational institutions doing so manually until that time), although that would only diffuse the sequential bias effect across more students. Second, graders should be trained on the nature of sequential bias and strategies to avoid it in their work, which still leaves the problem of the slog. Finally, to address the problem fully, institutions should limit the number of assignments evaluated by any one grader. Eliminating electronic submission and grading entirely—bound to be popular with many stakeholders looking to limit technology in education—may be the most obvious option not suggested here.

SOURCE: Zhihan (Helen) Wang, Jiaxin Pei, and Jun Li, “30 Million Canvas Grading Records Reveal Widespread Sequential Bias and System-Induced Surname Initial Disparity,” Management Science (March 2024).

NOTE: Today, the Ohio House Higher Education Committee invited testimony from state and national policy leaders as part of their exploratory hearings on science of reading implementation in Ohio. Fordham’s Vice President for Ohio Policy was one of the leaders invited to give testimony. These are his full written remarks.

My name is Chad Aldis, and I am the Vice President for Ohio Policy at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. The Fordham Institute is an education-focused nonprofit that conducts research, analysis, and policy advocacy with offices in Columbus, Dayton, and Washington, D.C.

Reading is essential for functioning in today’s society. Unfortunately, roughly 43 million American adults—about one in five—have poor reading skills.

Giving children a strong start in reading is job number one for elementary schools. An influential national study from the Annie E. Casey Foundation found that third graders who did not read proficiently were four times more likely to drop out of high school. A longitudinal analysis using Ohio data on third graders found strikingly similar results. The consequences of dropping out are well-documented: higher rates of unemployment, lower lifetime wages, and an increased likelihood of being involved in the criminal justice system.

State leaders have long understood the need for stronger literacy in Ohio schools. In 2012 for instance, the General Assembly passed the Third Grade Reading Guarantee, which calls for annual diagnostic testing in grades K-3 to screen for reading deficiencies; reading improvement plans for struggling readers; and parental notification when a child isn’t reading well. Though recently weakened, the reading guarantee also required schools to retain and provide extra support for third graders who did not meet state reading standards.

While the reading guarantee created a framework for reading intervention, it didn’t directly address curriculum and instruction. In more recent years, literacy experts and advocates—often parents—have pushed for increased attention to effective teaching methods and high quality curricula. Based on a wealth of research about how children best learn to read, they have insisted (and we at Fordham agree) that schools follow the “science of reading.”

You may have heard of that term before and there are slightly varying ways to define it, but in general the science of reading refers to an instructional approach that emphasizes phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension—what many call the five pillars of reading. Phonics tends to receive the lion’s share of attention—and it is of course foundational to effective early literacy. But it’s important to recognize that the other elements are also crucial. It takes more than simple word recognition to comprehend a passage. Rich vocabulary and background knowledge are also key ingredients to become strong, proficient readers.

It’s also important to understand practices that are not scientifically based instruction. The most common is a technique known as “three cueing,” which prompts children to guess at words based on a related picture or the word’s position in a sentence, instead of sounding words out. Cueing methods are embedded in widely used reading curricula, most notably Fountas & Pinnell Classroom and Lucy Calkins’ Units of Study. According to a recent survey by the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce (DEW), these programs were the fourth and sixth most frequently used core ELA curricula by Ohio elementary schools in 2022-23.

Science of reading legislation

Recognizing the need for more effective curriculum and instruction, Governor DeWine and this General Assembly included language in last year’s budget (HB 33) that requires elementary schools to align their literacy instruction with the science of reading. Key elements include:

High-quality instructional materials: HB 33 requires DEW to establish a list of core ELA curricula and intervention programs in grades K-5 that align with the science of reading. It further stipulates that all public schools must use materials from the state-approved list during the 2024–25 school year.

Professional development (PD): To support effective implementation of new curricula, HB 33 requires educators to complete a PD course in the science of reading (unless they’ve already completed similar training). Upon completion, stipends of either $400 or $1,200 are provided depending on the grade and subject taught. In addition, HB 33 also calls for literacy coaches that provide more intensive support for teachers serving in the state’s lowest performing schools.

Teacher preparation: Recent research has demonstrated that not all colleges of education have adequately prepared young teachers in the science of reading, HB 33 takes steps to ensure stronger, more consistent preparation. This is absolutely essential. Ohio is spending tens of million dollars on professional development to—in many cases—retrain teachers. New teachers coming out of our educator preparation programs need to be up-to-date on how best to teach students to read. The Ohio Department of Higher Education (ODHE) must implement audits that review programs’ alignment to the science of reading. The bill also requires the chancellor to revoke program approval if a review uncovers inadequate alignment and deficiencies are not addressed within a year.

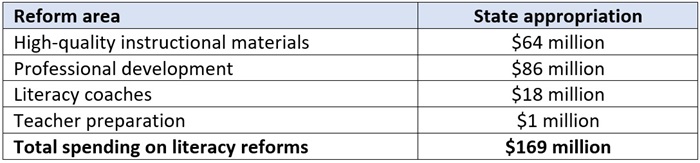

Substantial funds were allocated to support these activities. In total, the state will spend $169 million in FYs 2024 and 2025 to support the literacy initiative, with the largest portion going toward PD stipends ($86 million) and subsidies to purchase new curricula ($64 million). Another $18 million will support literacy coaches, and an additional $1 million is set aside to help teacher preparation programs transition to the science of reading (of which $150,000 supports the ODHE audits).

Table 1: State funding set aside for literacy reforms, combined amounts for FY24 and FY25

Early implementation

As you are all aware, it takes more than passing a bill to spur desired change in our schools. It also takes strong follow-through and buy-in from state and local leaders—what is often referred to as rigorous implementation. We are pleased to report that in recent months, Ohio has undertaken significant steps forward that lay the groundwork for effective school-level implementation. Here, I’d like to highlight two specific efforts but would be happy to answer questions you may have on other implementation elements at the conclusion of the presentation.

Establishing a list of high-quality ELA curricula. In advance of the curriculum requirement that will be in place in 2024-25, DEW—consistent with recent changes in law— implemented a vetting process to approve curricula aligned with the science of reading. In early March, the department announced a state-approved list of core ELA curricula that schools must choose from starting next school year. In total, the department approved fourteen core programs, among which include highly-respected programs that have a strong emphasis on both phonics and the knowledge-building elements needed for comprehension. This process also excluded programs that promote three-cueing.

Allocating funds to support schools needing to overhaul their ELA curricula. The department also recently allocated the $64 million set-aside to help districts and charter schools purchase state-approved ELA curricula. The allocation method relied on information collected in a statewide survey of schools’ pre-reform (2022–23) ELA curricula. The department categorized districts and charters into three groups. While the details about the grouping method are somewhat complex, the basic framework is as follows:

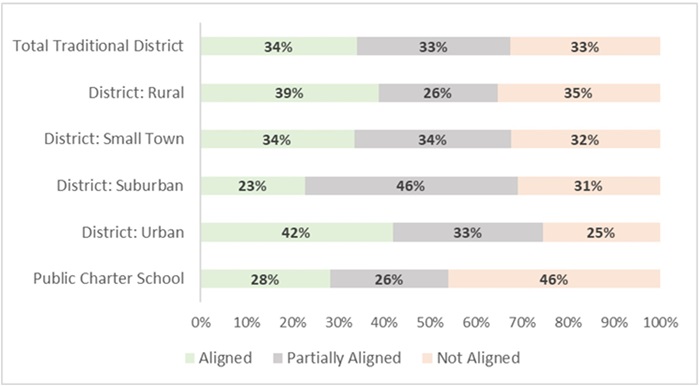

Figure 1 shows the breakdown of districts according to this grouping method. At the top of the figure we see that districts statewide were almost evenly split across the three categories. To their credit, one third of districts have already been using ELA curricula aligned with the science of reading. Districts in this category will be able to continue using their current program. Another one third of districts are partially aligned. They may continue to use their current supplemental materials—for instance, a phonics program that helps fill gaps—but will need to purchase a state-approved core ELA program. The final third of districts will need to completely overhaul their ELA curricula by installing a new program. The figure below also displays the breakdown of districts by typology (e.g., rural versus urban), and indicates that suburban districts and charter schools will likely be making the most significant changes in ELA curriculum in the coming year.

Figure 1: Districts and charter schools’ alignment (pre-reform) with Ohio’s new ELA curricula standards

Based on these groupings, the department allocated the bulk of the instructional material dollars to not-aligned districts that need to purchase new curricula to meet state requirements. On average, not-aligned districts received $121 per PK–5 student, while partially aligned and aligned districts received $101 and $37 per PK–5 student, respectively.

Final thoughts

Ohio is right to focus on literacy as the linchpin for greater student success and a more flourishing tomorrow. In closing, I would like to offer a few final comments.

First, stay the course on the literacy initiative. Right now, there is a lot of momentum behind the science of reading. That’s a good thing, as it has focused attention on the urgent need for stronger curriculum and instruction. But as we all know, enthusiasm for various reforms can wax and wane. Helping more children learn to read proficiently through more effective practices will take significant time and patience. In the days and months ahead, it will be crucial for Ohio to keep its eye on the ball, and not let up.

Second, continue to invest in the science of reading. House Bill 33 provided a generous down-payment on the state’s renewed effort to boost reading proficiency. But implementation won’t stop in June 2025. In fact, the work of fully equipping all teachers to effectively use high-quality curricula is likely to continue in earnest for several years to come. Ohio should continue to set-aside dollars that support strong professional learning, and to meet curriculum needs that might extend beyond core instruction. As the initiative progresses, policymakers would also be smart to set aside dollars for research and evaluation. Results from evaluative studies would help support school leaders as they continue to make decisions about which materials to put into teachers’ hands, and how best to support their work in the classroom.

Third, don’t forget why all this matters: Rigorous implementation of the science of reading promises higher student achievement and a more prosperous future for Ohio and its citizens. At this point, it’s worth pausing to consider the impressive gains of Mississippi, a state that was once criticized for having low student achievement. The Magnolia State recognized the need for stronger literacy instruction more than a decade ago and was one of the nation’s earliest adopters of a science of reading law.

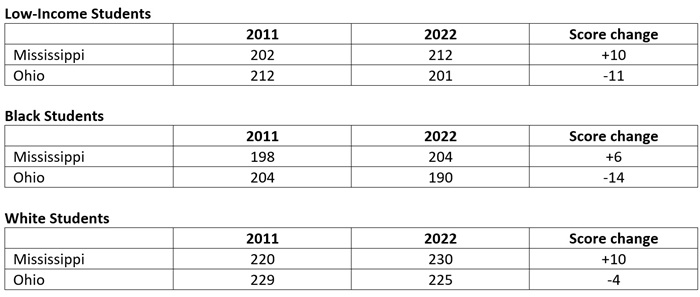

The tables below show the average scores on the 4th grade reading National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP, for Mississippi and Ohio. As you can see, Mississippi’s major student groups have made significant improvements over the past decade. The reading scores of Mississippi’s low-income students are up 10 points from their scores in 2011—and as context a 10-point gain is roughly equivalent to a grade level. Scores are also up by 6 and 10 points for Mississippi’s Black and white students respectively. Impressively, all three of these student groups read at higher levels today than their peer groups in Ohio. Let me say that again, Mississippi students in each student group read better—sometimes much better—than their peers in Ohio.

Table 2: Ohio versus Mississippi’s performance on 4th grade NAEP reading by subgroup, 2011 to 2022

No one can predict whether Ohio will ultimately achieve the same level of progress that Mississippi has accomplished. But it does illustrate what can happen on behalf of students when state leaders and local educators commit themselves to thoroughly implementing the science of reading. And based on studies by Stanford University economist Eric Hanushek, we can be confident that boosting the literacy skills of today’s students will pay off with stronger economic growth in the years to come.[1]

We at Fordham couldn’t be more excited about the next chapter in Ohio’s effort to improve literacy. A strong law is in place, and implementation is off and running. Let’s keep our eyes on the prize, and continue to follow through on behalf of Ohio’s 1.6 million public school students.

[1] His economic models predict that, if Ohio were to get all students to “basic” on NAEP (one level below proficient), it would roughly double its future economic output.