NOTE: Today, the Ohio House Higher Education Committee invited testimony from state and national policy leaders as part of their exploratory hearings on science of reading implementation in Ohio. Fordham’s Vice President for Ohio Policy was one of the leaders invited to give testimony. These are his full written remarks.

My name is Chad Aldis, and I am the Vice President for Ohio Policy at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. The Fordham Institute is an education-focused nonprofit that conducts research, analysis, and policy advocacy with offices in Columbus, Dayton, and Washington, D.C.

Reading is essential for functioning in today’s society. Unfortunately, roughly 43 million American adults—about one in five—have poor reading skills.

Giving children a strong start in reading is job number one for elementary schools. An influential national study from the Annie E. Casey Foundation found that third graders who did not read proficiently were four times more likely to drop out of high school. A longitudinal analysis using Ohio data on third graders found strikingly similar results. The consequences of dropping out are well-documented: higher rates of unemployment, lower lifetime wages, and an increased likelihood of being involved in the criminal justice system.

State leaders have long understood the need for stronger literacy in Ohio schools. In 2012 for instance, the General Assembly passed the Third Grade Reading Guarantee, which calls for annual diagnostic testing in grades K-3 to screen for reading deficiencies; reading improvement plans for struggling readers; and parental notification when a child isn’t reading well. Though recently weakened, the reading guarantee also required schools to retain and provide extra support for third graders who did not meet state reading standards.

While the reading guarantee created a framework for reading intervention, it didn’t directly address curriculum and instruction. In more recent years, literacy experts and advocates—often parents—have pushed for increased attention to effective teaching methods and high quality curricula. Based on a wealth of research about how children best learn to read, they have insisted (and we at Fordham agree) that schools follow the “science of reading.”

You may have heard of that term before and there are slightly varying ways to define it, but in general the science of reading refers to an instructional approach that emphasizes phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension—what many call the five pillars of reading. Phonics tends to receive the lion’s share of attention—and it is of course foundational to effective early literacy. But it’s important to recognize that the other elements are also crucial. It takes more than simple word recognition to comprehend a passage. Rich vocabulary and background knowledge are also key ingredients to become strong, proficient readers.

It’s also important to understand practices that are not scientifically based instruction. The most common is a technique known as “three cueing,” which prompts children to guess at words based on a related picture or the word’s position in a sentence, instead of sounding words out. Cueing methods are embedded in widely used reading curricula, most notably Fountas & Pinnell Classroom and Lucy Calkins’ Units of Study. According to a recent survey by the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce (DEW), these programs were the fourth and sixth most frequently used core ELA curricula by Ohio elementary schools in 2022-23.

Science of reading legislation

Recognizing the need for more effective curriculum and instruction, Governor DeWine and this General Assembly included language in last year’s budget (HB 33) that requires elementary schools to align their literacy instruction with the science of reading. Key elements include:

High-quality instructional materials: HB 33 requires DEW to establish a list of core ELA curricula and intervention programs in grades K-5 that align with the science of reading. It further stipulates that all public schools must use materials from the state-approved list during the 2024–25 school year.

Professional development (PD): To support effective implementation of new curricula, HB 33 requires educators to complete a PD course in the science of reading (unless they’ve already completed similar training). Upon completion, stipends of either $400 or $1,200 are provided depending on the grade and subject taught. In addition, HB 33 also calls for literacy coaches that provide more intensive support for teachers serving in the state’s lowest performing schools.

Teacher preparation: Recent research has demonstrated that not all colleges of education have adequately prepared young teachers in the science of reading, HB 33 takes steps to ensure stronger, more consistent preparation. This is absolutely essential. Ohio is spending tens of million dollars on professional development to—in many cases—retrain teachers. New teachers coming out of our educator preparation programs need to be up-to-date on how best to teach students to read. The Ohio Department of Higher Education (ODHE) must implement audits that review programs’ alignment to the science of reading. The bill also requires the chancellor to revoke program approval if a review uncovers inadequate alignment and deficiencies are not addressed within a year.

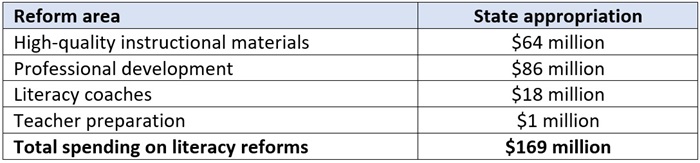

Substantial funds were allocated to support these activities. In total, the state will spend $169 million in FYs 2024 and 2025 to support the literacy initiative, with the largest portion going toward PD stipends ($86 million) and subsidies to purchase new curricula ($64 million). Another $18 million will support literacy coaches, and an additional $1 million is set aside to help teacher preparation programs transition to the science of reading (of which $150,000 supports the ODHE audits).

Table 1: State funding set aside for literacy reforms, combined amounts for FY24 and FY25

Early implementation

As you are all aware, it takes more than passing a bill to spur desired change in our schools. It also takes strong follow-through and buy-in from state and local leaders—what is often referred to as rigorous implementation. We are pleased to report that in recent months, Ohio has undertaken significant steps forward that lay the groundwork for effective school-level implementation. Here, I’d like to highlight two specific efforts but would be happy to answer questions you may have on other implementation elements at the conclusion of the presentation.

Establishing a list of high-quality ELA curricula. In advance of the curriculum requirement that will be in place in 2024-25, DEW—consistent with recent changes in law— implemented a vetting process to approve curricula aligned with the science of reading. In early March, the department announced a state-approved list of core ELA curricula that schools must choose from starting next school year. In total, the department approved fourteen core programs, among which include highly-respected programs that have a strong emphasis on both phonics and the knowledge-building elements needed for comprehension. This process also excluded programs that promote three-cueing.

Allocating funds to support schools needing to overhaul their ELA curricula. The department also recently allocated the $64 million set-aside to help districts and charter schools purchase state-approved ELA curricula. The allocation method relied on information collected in a statewide survey of schools’ pre-reform (2022–23) ELA curricula. The department categorized districts and charters into three groups. While the details about the grouping method are somewhat complex, the basic framework is as follows:

- Aligned districts used a state-approved core curriculum.

- Partially aligned districts used only a state-approved supplemental program.

- Not aligned districts used neither a state-approved core nor supplemental program.

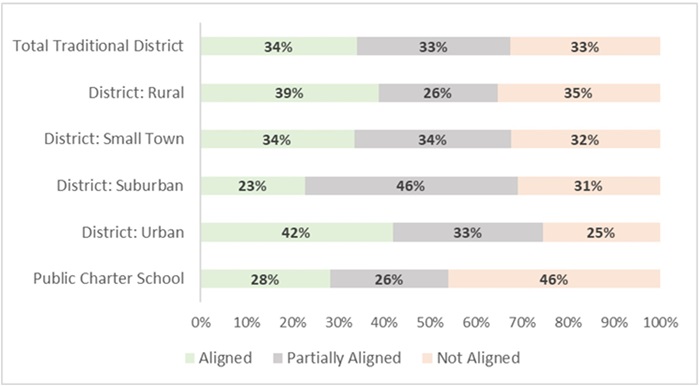

Figure 1 shows the breakdown of districts according to this grouping method. At the top of the figure we see that districts statewide were almost evenly split across the three categories. To their credit, one third of districts have already been using ELA curricula aligned with the science of reading. Districts in this category will be able to continue using their current program. Another one third of districts are partially aligned. They may continue to use their current supplemental materials—for instance, a phonics program that helps fill gaps—but will need to purchase a state-approved core ELA program. The final third of districts will need to completely overhaul their ELA curricula by installing a new program. The figure below also displays the breakdown of districts by typology (e.g., rural versus urban), and indicates that suburban districts and charter schools will likely be making the most significant changes in ELA curriculum in the coming year.

Figure 1: Districts and charter schools’ alignment (pre-reform) with Ohio’s new ELA curricula standards

Based on these groupings, the department allocated the bulk of the instructional material dollars to not-aligned districts that need to purchase new curricula to meet state requirements. On average, not-aligned districts received $121 per PK–5 student, while partially aligned and aligned districts received $101 and $37 per PK–5 student, respectively.

Final thoughts

Ohio is right to focus on literacy as the linchpin for greater student success and a more flourishing tomorrow. In closing, I would like to offer a few final comments.

First, stay the course on the literacy initiative. Right now, there is a lot of momentum behind the science of reading. That’s a good thing, as it has focused attention on the urgent need for stronger curriculum and instruction. But as we all know, enthusiasm for various reforms can wax and wane. Helping more children learn to read proficiently through more effective practices will take significant time and patience. In the days and months ahead, it will be crucial for Ohio to keep its eye on the ball, and not let up.

Second, continue to invest in the science of reading. House Bill 33 provided a generous down-payment on the state’s renewed effort to boost reading proficiency. But implementation won’t stop in June 2025. In fact, the work of fully equipping all teachers to effectively use high-quality curricula is likely to continue in earnest for several years to come. Ohio should continue to set-aside dollars that support strong professional learning, and to meet curriculum needs that might extend beyond core instruction. As the initiative progresses, policymakers would also be smart to set aside dollars for research and evaluation. Results from evaluative studies would help support school leaders as they continue to make decisions about which materials to put into teachers’ hands, and how best to support their work in the classroom.

Third, don’t forget why all this matters: Rigorous implementation of the science of reading promises higher student achievement and a more prosperous future for Ohio and its citizens. At this point, it’s worth pausing to consider the impressive gains of Mississippi, a state that was once criticized for having low student achievement. The Magnolia State recognized the need for stronger literacy instruction more than a decade ago and was one of the nation’s earliest adopters of a science of reading law.

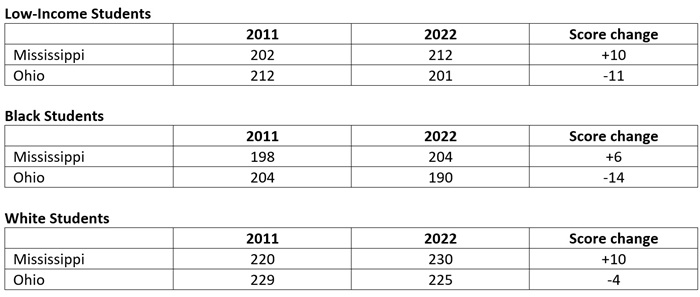

The tables below show the average scores on the 4th grade reading National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP, for Mississippi and Ohio. As you can see, Mississippi’s major student groups have made significant improvements over the past decade. The reading scores of Mississippi’s low-income students are up 10 points from their scores in 2011—and as context a 10-point gain is roughly equivalent to a grade level. Scores are also up by 6 and 10 points for Mississippi’s Black and white students respectively. Impressively, all three of these student groups read at higher levels today than their peer groups in Ohio. Let me say that again, Mississippi students in each student group read better—sometimes much better—than their peers in Ohio.

Table 2: Ohio versus Mississippi’s performance on 4th grade NAEP reading by subgroup, 2011 to 2022

No one can predict whether Ohio will ultimately achieve the same level of progress that Mississippi has accomplished. But it does illustrate what can happen on behalf of students when state leaders and local educators commit themselves to thoroughly implementing the science of reading. And based on studies by Stanford University economist Eric Hanushek, we can be confident that boosting the literacy skills of today’s students will pay off with stronger economic growth in the years to come.[1]

We at Fordham couldn’t be more excited about the next chapter in Ohio’s effort to improve literacy. A strong law is in place, and implementation is off and running. Let’s keep our eyes on the prize, and continue to follow through on behalf of Ohio’s 1.6 million public school students.

[1] His economic models predict that, if Ohio were to get all students to “basic” on NAEP (one level below proficient), it would roughly double its future economic output.