Last year, state policymakers unveiled a bold plan to improve early literacy in Ohio. The centerpiece of that plan is the science of reading, a research-based instructional approach that emphasizes phonics and knowledge building.

Given the intense focus on what’s new and different about these reforms, one might assume that Ohio’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee—passed more than a decade ago—is a thing of the past. But that’s not the case. The guarantee’s controversial retention requirement was unfortunately watered down, but many of its other provisions remain in place. One such provision requires districts and charter schools that meet certain criteria to submit a Reading Achievement Plan (RAP) to the state. As the name suggests, a RAP focuses on student achievement in reading, and must include analyses of student data and measurable performance goals.

Last year, the Department of Education and Workforce (DEW) released a list of districts and charter schools that were required to submit a new RAP to the state by December 31. As of this writing, DEW’s website also contains RAPs from the 2018–19 school year. Quite a bit happened between 2018 and 2023, namely a once-in-a-generation pandemic that had massive impacts on student achievement. But that’s exactly why comparing a district’s 2018 RAP to its updated 2023 plan is a useful exercise for state leaders. In each plan, districts and schools were required to identify any internal or external factors that they believed contributed to underachievement in reading. Factors that persisted through—or worsened during—the pandemic should be considered potential threats to Ohio’s latest early literacy initiative.

Several districts were required to submit RAPs in both 2018 and 2023, but this piece will compare the plans submitted by just one of them: Columbus City Schools (CCS). Columbus is an ideal case study, as it’s the largest district in the state and has a history of troublingly low reading achievement. In short, contributing factors that are consistent in Columbus over time are likely present elsewhere. Although these plans contain plenty of more obvious reading-related issues to consider, here are three significant concerns that policymakers should keep an eye on going forward.

1. Chronic absenteeism

In both the 2018 and 2023 plans, CCS identified chronic absenteeism—defined by the state as missing at least 10 percent of instructional time for any reason—as a factor contributing to underachievement in literacy. Given the well-known and far-reaching negative impacts of chronic absenteeism, it’s a no-brainer for district officials to flag it as a key problem. But it’s also important to recognize just how alarmingly high the district’s chronic absenteeism rates are in the earliest grade levels.

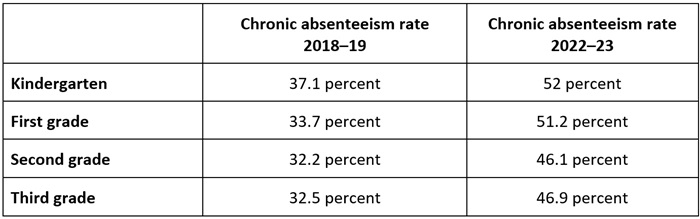

Table 1: Chronic absenteeism rates of Columbus City School students in grades K–3

Table 1 indicates that chronic absenteeism rates in Columbus were high prior to the pandemic—a third or more of students in grades K–3 met the state’s identification threshold—and are even higher in the wake of it. With roughly half of all elementary students missing a significant amount of school, it’s no wonder that just 35 percent of Columbus third graders were proficient in reading last year.

Student attendance woes aren’t unique to Columbus. Hundreds of districts across the state are also struggling with chronic absenteeism rates that shot up during the pandemic and have yet to come back down, and absenteeism has long been particularly problematic for the youngest and oldest students. If state policymakers are serious about improving early literacy in Columbus (and hundreds of other districts in the same boat), they must improve student attendance as a bedrock principle. That means supporting innovative incentive ideas to get kids to attend school. It means holding adults—the staff responsible for making schools the kinds of places kids want to be, and the parents responsible for ensuring kids get there—accountable. Most importantly, it means continuing to transparently track student attendance, resisting efforts to make it easier for kids to miss school, and ensuring that school calendar laws send the right message about the importance of consistent attendance.

2. Teacher shortages

Both plans reference staffing shortages, particularly in regard to substitutes, as another factor that contributed to underachievement. The 2018 plan notes that a “consistent lack of qualified substitutes” contributed to the district’s “inability to access teachers and provide ongoing and intensive professional development.” The 2023 plan also mentions substitute teachers, claiming that during the three most recent school years, there were “inconsistencies in classroom instruction due to the lack of substitute coverage.” The most recent plan also mentions broader teacher shortages that extend beyond subs. Because of these shortages, district officials say, many PreK–5 teachers “have been forced to teach outside their areas of expertise and/or with larger class sizes.”

As was the case with chronic absenteeism, Columbus is not the only district grappling with staffing issues. The good news is that after years of declines, enrollment in Ohio’s teacher preparation programs is trending upward. Also in the good news column are state initiatives like a teacher apprenticeship program, a grow your own teacher scholarship, and policy tweaks aimed at expanding the pool of substitute teachers. These initiatives should help bolster the teacher pipeline from the largest district on down.

But that doesn’t mean state leaders can rest on their laurels. It’s crucial to get right the teacher preparation audits that were included in the literacy reform package. If not, we run the risk that an otherwise welcome influx of new teachers will turn into a nightmare because they lack proper training. To avoid this pitfall in districts large and small, lawmakers will need to allocate more funding for audits in the upcoming state budget and stand strong against likely pushback from higher education.

3. Professional development

In last year’s state budget, lawmakers allocated considerable sums toward helping current teachers understand and implement the science of reading. Over the next biennium, $86 million will go toward professional development. Another $18 million will pay for literacy coaches, who will be charged with providing intensive support to teachers in the state’s lowest performing schools.

If this state investment had occurred in 2018, CCS officials likely would have been thrilled. That’s because, in their 2018 RAP, they identified professional development as a factor contributing to their underachievement. Beyond the substitute teacher issues outlined above, the plan also notes that the district needs to “further define the role of instructional coaches related to literacy,” as well as “identify a mechanism for ongoing instructional support for teachers to ensure effective implementation of high impact reading instructional strategies.”

Given these stated aims, one might think that the district’s 2023 plan would have good news on the professional development front. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. The 2023 plan notes that, although the district has provided “multiple opportunities” for teachers to receive professional development related to new curriculum resources for literacy, “many teachers have failed to complete training due to professional development being outside the contractual workday.”

The good news for Columbus leaders is that professional development in reading science is no longer optional. The state budget requires teachers and administrators to complete a professional development course in the science of reading. The state also addressed concerns about teachers working outside contractual work hours by offering stipends of up to $1,200 to those who complete the course.

For state leaders, on the other hand, professional development struggles in Ohio’s largest district should serve as a warning sign. Even with mandates and stipends in place, getting every teacher on board with the science of reading will take unwavering commitment—something that hasn’t historically described Ohio lawmakers. State leaders may also need to provide more funding in the upcoming budget to cover the cost of curriculum-specific training, additional literacy coaches, and other types of support.

***

These aren’t the only potential pitfalls facing Ohio on its road toward improved reading achievement, but they are big and noteworthy. Their existence in both the 2018 and 2023 Columbus RAPs indicates they are persistent. And if they’re happening in the state’s largest district, many other districts are likely experiencing their own version of the same. Going forward, state and local leaders must do everything in their power to proactively address these issues. Otherwise, the science of reading push could founder.