It’s important to give Ohio school districts’ reopening plans a close look, even if they’re now void in the many locales around the state that will start the fall fully online. Eventually—hopefully sooner rather than later—this pandemic will fade, and schools will be right back in the positions they were in earlier this summer, needing to create reopening plans again. These initial drafts could give us a glimpse of what might happen down the road.

Columbus and Dayton are instructive examples. On July 28, Columbus City Schools (CCS) announced that it would reopen entirely online this fall. A few days later, Dayton Public Schools (DPS) announced that it would do the same. But remote learning wasn’t always the plan. A few weeks ago, both districts published reopening plans that included at least some type of in-person instruction.

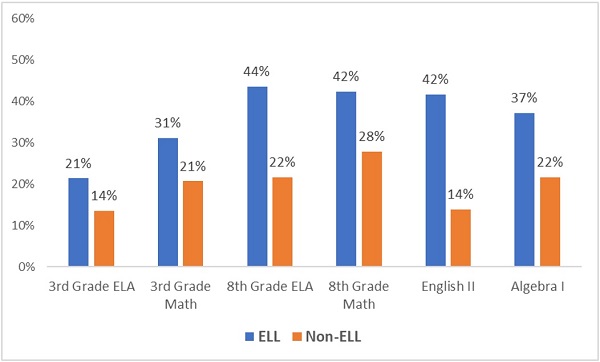

Although they share several similarities in regard to student demographics and achievement, the two district’s reopening plans were very different. Dayton planned to hit the ground running and resume regular, in-person classes for all students. Columbus, on the other hand, chose to ease back in with a blended model that had students in grades K–8 attending in-person two days a week and learning at home during the other three. Students in grades 9–12 would have been fully remote. Both districts also planned to offer a fully online option for families who were hesitant to send their students back in-person. In Dayton, families were required to commit to the “totally digital” option for the duration of the school year. In Columbus, students had (and still have) the option of enrolling in CCS Digital Academy, but are only required to remain enrolled for the first semester of the year.

The upshot is that two of Ohio’s largest districts initially planned to take very different approaches to reopening. It’s too early to know how similar their future reopening plans will be to their original ones. But the reasoning behind the initial decisions is important.

For instance, some of the differences were likely attributable to health data. Columbus and Dayton are located in counties with very different Covid-19 numbers. Columbus is in Franklin County, where case and death counts are the highest in the state. Dayton, on the other hand, is located in Montgomery County, where numbers are lower (though still high). Based on this data, it’s understandable why CCS was more hesitant to fully reopen than Dayton.

But health data isn’t the only data that matters. In its initial reopening announcement, DPS said that it made decisions “after consultations with the Department of Health, other Montgomery County school districts, and in consideration of parent survey results.” The results of these surveys don’t appear to be posted anywhere, but the district previously stated that they were “overwhelmingly in favor of resuming normal, in-person classes this fall.” CCS also conducted parent surveys. But unlike DPS, its results were mixed: 38 percent favored their children attending in-person, 24 percent favored attending online, and 38 percent preferred a combination of both. Although it’s impossible to be sure without examining DPS’s survey results, it appears that both districts were responding to what their families wanted.

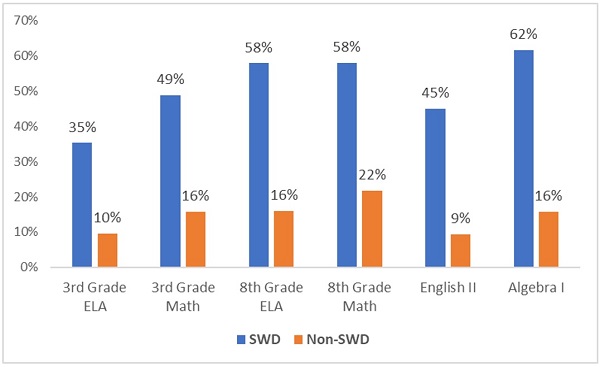

There are other issues to consider, too. “The key factor in making the decision was the fact that we have to have our kids back in school,” DPS superintendent Elizabeth Lolli told reporters after the district’s initial announcement. “I had 600 of my students not showing up online (at all this spring) and depending on the school, I was anywhere between 35% and 76% of students showing up for the online lessons. I can’t have that kind of ratio of learning occurring in the district.” In a separate media story that also emphasized attendance issues, Lolli told reporters, “If we have to stay on remote learning this school year, we will lose a generation of readers.”

CCS didn’t explicitly acknowledge spring attendance issues in its initial plan. The district did note that it would track both student attendance and idle time for students in its Digital Academy, and attendance for high schoolers who were learning remotely. For the most part, though, the majority of CCS’s focus seemed to be on health and safety concerns rather than in-person learning. “We want to make sure that our students enter, [and] come to school safe,” Superintendent Talisa Dixon told reporters. “If we cannot do that with the current number of cases, then we won’t do it...we will not put our students, families and staff in jeopardy.”

Of course, that’s not to say that DPS wasn’t focused on health and safety. It’s just that Columbus and Dayton reflected two sides of a larger debate about how to reopen schools. And therein lies the rub. Even if every district in the state opts to go virtual this fall, in-person reopening won’t cease to be an issue. It’ll just be kicked down the road. Eventually, schools will be faced with the same decisions again. School leaders will be right back in the unenviable position of balancing the health and safety of students and staff with the serious academic consequences of extended school closures, all in the midst of one of the most divisive periods in our nation’s history.

There are no easy answers. But if there’s one thing we’ve learned over the last few months, it’s how unpredictable this pandemic is. Going forward, flexibility will be key. And in that regard, Ohio’s districts have already proven that they’re on the right path.