In the education world, the last couple months have been awash in news and commentary about sagging student achievement in the wake of the pandemic. The story is no different in Ohio, where students have also lost significant ground compared to pre-pandemic cohorts. Proficiency rates on Ohio’s high school algebra exam, for example, are down from 61 to 49 percent between 2018–19 and 2021–22. For economically disadvantaged students, proficiency rates on this exam decreased from 42 to 30 percent; for Black students, rates slid from 30 to just 19 percent. It’s not just algebra, either. State test results are troubling in other grades and subjects, too, and recently released national assessment data likewise show serious academic decline.

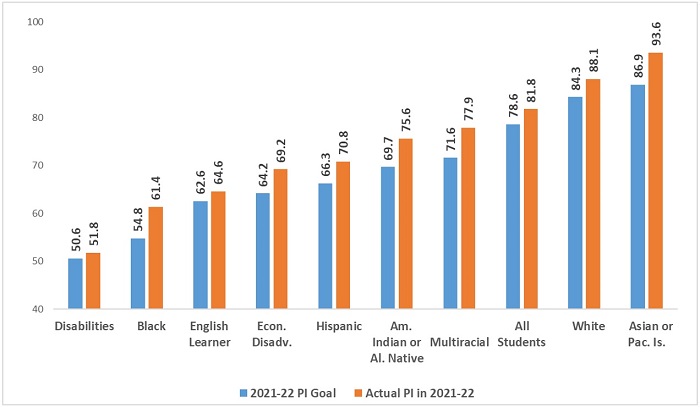

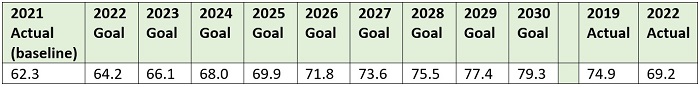

Given these data, it might surprise you to learn that Ohio students crushed the state’s annual achievement goals that are set forth in its federally-required ESSA Plan. The figures below show the performance index scores of the various subgroups whose achievement must be “disaggregated” under federal and state law. The top chart shows that every subgroup topped the state’s achievement goal in English language arts (ELA)—in some cases by fairly wide margins. For example, the ELA performance index score of economically disadvantaged students was 69.2 versus a goal of 64.2. In math, performance against goals was slightly less impressive, but every subgroup, except for students with disabilities, beat its goal.

Figure 1: ELA (top) and math (bottom) performance index scores—actual versus goal—in 2021–22 by subgroup

What gives?

The backstory—and it gets into the weeds—is this. Federal law requires states to establish “ambitious” yearly achievement targets, but in reality, states can set their expectations just about wherever they’d like. Earlier this year, the Ohio Department of Education amended the state’s goals. Recognizing pandemic learning losses, the department slashed the subgroup goals by anywhere from 5 to 26 points, depending on subject and student group. For instance, the department’s ELA goal for economically disadvantaged students was initially an index score of 77.3 for 2021–22, but that number was adjusted to 64.2—a 13-point cut.

Some downshift was probably sensible, but the department went too far in dampening expectations. One issue is that department relied on 2020–21 performance index scores to create a baseline—and those scores were depressed not just from learning loss, but also because of higher numbers of untested students.[1] Fewer students took state exams that year, and untested students count as zeros in the performance index calculations. This artificial “deflation” doesn’t seem to have been accounted for. In fact, economically disadvantaged students could have likely met the state’s 2021–22 goal simply by virtue of greater test participation, not any real academic improvement.

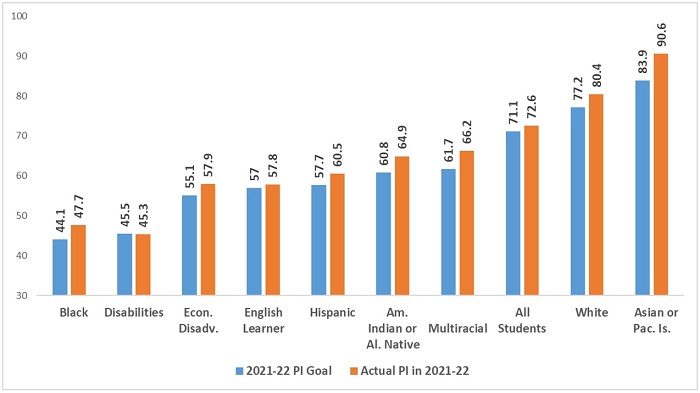

The department might be forgiven for setting extremely modest goals for 2021–22. But what is less pardonable are persistently low expectations for achievement that continue well into the future. Table 1 shows that Ohio doesn’t expect economically disadvantaged students to perform on par with their pre-pandemic counterparts until 2027–28. That’s an inadequate expectation, especially in ELA where the losses have been less severe, rebound has been more evident, and some experts are predicting that full recovery could occur within three years (math may take longer). This goal could be seen as another example of the oft-discussed “soft bigotry of low expectations.”

Table 1: Ohio’s amended ELA performance index goals for economically disadvantaged students

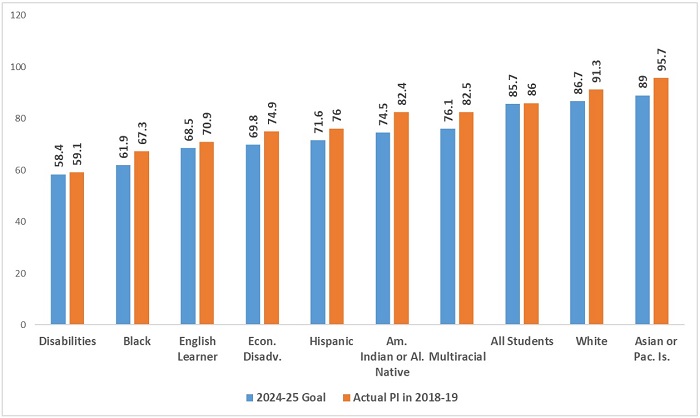

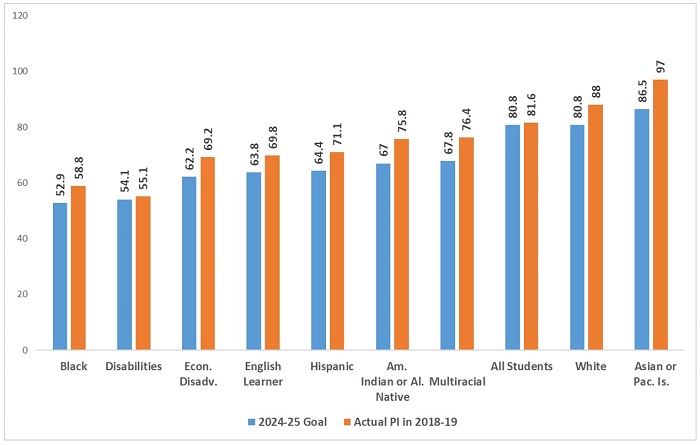

Figure 2 shows that such mediocre goals aren’t limited to economically disadvantaged students, but exist for other groups, as well. These charts display the state’s 2024–25 achievement goals versus the pre-pandemic performance index scores of each subgroup. There is no instance in which the state expects a subgroup to meet pre-pandemic achievement levels by this year, and for some subgroups, the goal is quite a bit lower. For example, by 2024–25, Black students are expected to post an ELA index score of only 61.9, even though their pre-pandemic peers scored 67.3.

Figure 2: ELA (top) and math (bottom) performance index scores—actual in 2018–19 versus 2024–25 goal—by subgroup

Setting low achievement goals has implications for both policy and practice. For one, these goals are used in Ohio’s report card system, as schools’ Gap Closing ratings are based in part on whether subgroups achieve these targets. One consequence of softening targets in 2021–22 was that most schools received rosy Gap Closing ratings—more than 60 percent received four or five stars—even at a time when students were struggling with serious learning loss. Such ratings could be misleading the public into thinking that schools are narrowing gaps when, in fact, they are widening.

Perhaps more important is what these goals communicate to schools. They seem to say “it’s OK for learning losses to persist well into the second half of this decade.” That message is exactly the wrong one for state leaders to send Ohio schools. Instead, the state’s achievement goals should be incentivizing schools to go above and beyond the status quo on behalf of students who, by no fault of their own, lost significant ground during the pandemic.

In a recent piece, my Fordham colleagues Amber Northern and David Griffith write, “If we’re serious about getting our students back on track, we must be even more serious about getting our expectations for them back on track.” They are right. We do need to get back to having high expectations for all Ohio students.

The department should scrap these “pandemic-adjusted” goals and start fresh, with an eye towards full recovery by 2024–25. Some may think that’s too ambitious. Some might worry about dinging schools’ ratings. Perhaps Ohio’s amended goals are already locked in with the feds (it’s not clear if they’ve been approved). If that’s the case, fine. Let’s create a set of “real” achievement goals that Ohio’s leaders and schools can get behind. But fears and bureaucracy shouldn’t stop us from setting aspirational targets that motivate schools to achieve something big for Ohio students.

[1] 6.4 percent of Ohio students were untested in 2020–21 (compared to 2.0 percent in 2021–22). Had the untested students taken an assessment, they would have generated a minimum number of points towards the index score.