- It’s the end of the traditional school year across Ohio and that means only one thing: a dearth of actual education news in publications far and wide. As you can see. Nonetheless, we start today with a pretty interesting profile of the valedictorian of this year’s senior class at Ponitz Career Technology Center in Dayton. She is Turkan Tashtan. Her family fled Russia when she was 8 and they eventually settled in Dayton after a brief stop in Pennsylvania. She spoke no English and had never attended school before. Her educational journey included an ESL track, a Dayton charter school, and finding and choosing Ponitz for high school. She has her eye on becoming a lawyer or a business leader someday. Best of luck in everything! (Dayton Daily News, 6/2/17)

- Everything is apparently awesome – I’m talking balloons, confetti, track meets, and hot Cheetos awesome – when you’re part of the team at the Colossus of Lorain (a.k.a. the academically-distressed district’s schmancy new-ish high school). In fact, the term “academic distress” is not mentioned once in this piece – a look back at the year just completed from the perspective of first-year Lorain High School principal Robin Hopkins. She does mention that little “attendance problem” we discussed last week, but it appears more of a minor blip in the awesomeness as Ms. Hopkins tells it than the giant yawning problem the supe was describing. She also expresses what sounds like a bittersweet farewell to the OGTs. Odd. Happy summer everyone! (Northern Ohio Morning Journal, 6/4/17)

- Speaking of summer in an academically distressed school district, I invite you all to take a look at this frankly amazing-sounding summer school program in Youngstown. Concentrated catch up opportunities for every grade level, every test (second OGT reference of the day; you're welcome, Aaron!), and probably every class. Free of charge, conducted by district teachers, with transportation and meals provided. Younger kids even get a camp-like component to balance out the academic portion and a program to assist them in transitioning to the next grade. This is absolutely fantastic. No frickin’ wonder it has triple the registration of previous versions. Kudos to all involved! A productive summer is sure to result. (Youngstown Vindicator, 6/3/17)

With President Trump and Secretary DeVos advocating for a federal school voucher initiative, private school choice is having its moment in the spotlight. One question that has been raised by critics, including on Capitol Hill, is whether private schools would be required to follow civil rights laws if they became recipients of federal funds.

I thought it might be helpful to understand the current obligations of private schools when it comes to civil rights, and how that varies (if at all) for schools participating in state voucher programs. Since the vast majority of private schools are religious, it’s also important to understand what rules are in place to protect their “free exercise of religion” under the First Amendment. I couldn’t find a good primer on this online, so I decided to take a crack at one.

Mainly at issue is whether private schools may choose not to enroll students or hire teachers on the basis of race, sex, sexual orientation, religion, or disability status. Let’s take a look.

Race

Thanks to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, plus a number of Supreme Court cases decided since then, no private school can discriminate on the basis of race, color, or national origin, in admissions or in hiring, or anything else; those that do would lose their non-profit status from the Internal Revenue Service. These IRS regulations enumerate over forty steps that civil rights enforcers should examine when determining if a private school is acting in a racially discriminatory manner.

Sex

Title IX ensures that public schools do not discriminate on the basis of sex, though decade-old regulations do allow for single-gender public schools if certain conditions are met. Title IX does not apply to private schools unless they receive federal funds; this allows them the option of remaining single-gender schools. Title IX does not apply to religious schools “to the extent that application of Title IX would be inconsistent with the religious tenets of the organization,” even if they do receive federal funds.

Private schools must abide by the Equal Employment Opportunity’s act ban on gender discrimination in hiring, unless they are religiously controlled.

Sexual Orientation

Congress has never enacted civil rights protections based on sexual orientation. As a result, private schools are not required to admit LGBT students, or the children of LGBT parents, or hire LGBT teachers, at least under federal law. States can institute their own protections, but Maryland is the only state that has prohibited private schools participating in school choice programs from discriminating on the basis of sexual orientation.

[RELATED CONTENT: “What Betsy DeVos should say about vouchers, LGBT rights, and religious liberty,” by Michael J. Petrilli.]

Religion

Religiously-controlled private schools are allowed to consider religion in admissions decisions. However, a handful of state school choice programs, including the one in Washington, D.C., require participating private schools to admit students regardless of religion.

Religiously-controlled private schools can discriminate on the basis of religion in hiring decisions. For example, Jewish schools are under no obligation to consider Catholic or Muslim teachers for their faculty.

Protections for students with disabilities

Many students with disabilities attend private schools that are under contract with public and charter schools; these students retain their right to a “free and appropriate public education,” or FAPE, in a “least restrictive environment,” or LRE. However, if a family chooses to forego the services offered by their public schools, required by their Individualized Education Plan, and opts for a “parental placement” for their child instead, they also give up FAPE and LRE.

Under the Americans with Disabilities Act, private schools must be willing to provide “auxiliary aids and services” to students with disabilities who are otherwise qualified for admission, so long as these accommodations would not change the fundamental nature of the program or result in significant difficulty or expense. Additional requirements under the ADA follow if the school receives public funds (such as through a state voucher program). In that case, schools cannot exclude a voucher participant based on disability if, “with minor adjustments,” such a student could reasonably participate in the private school’s education program. However, if a private school does not offer programs designed to meet a student’s special needs, the private school’s inability to serve that child is not considered discrimination. Religiously-controlled schools are exempted from these ADA requirements unless they receive federal funding.

- We start today with an opinion piece from the PD in which education professionals attempt to dispel misconceptions about standardized testing in Ohio’s schools. Good stuff. Now, why that had to be done in an opinion piece is still an open question. (Cleveland Plain Dealer, 5/31/17) On a related note, Ohio appears to have a bit of a test problem at the moment. No, not that one. This one: In the first year that all high school juniors in Ohio are required to take the ACT, about 1,300 test takers in 21 districts across the state have had their scores invalidated due to a mix up in test forms distributed. The result is that those students’ tests have been rejected with no scores reported. Test takers in Reynoldsburg, their families, and their school officials are pretty upset by the snafu. (Columbus Dispatch, 6/1/17) And so are test takers in the Miami Valley, their families, and their school officials. (Dayton Daily News, 6/1/17) Additionally, the remedy current on offer – a voucher for a free retest at the earliest available opportunity – isn’t sitting too well with those folks either. Story developing, as they say.

- I know it’s not Thursday, but how about a throwback to the good old days of raucous anti-Common Core testimony in the state legislature, full of hyperbole, misstatements, and tears? Simple: one only has to look back to this past Tuesday, when the good old days of raucous anti-Common Core testimony happened again. Again?! (Gongwer Ohio, 5/31/17)

- When is a barrage of unsolicited postcards not a barrage? When the foundation that raises money for a school district sends them to district graduates, apparently. Just ask the president of Toledo City Schools’ board of trustees, who is also a member of the board of said foundation. (What are the odds?!) Someone should have mentioned this to the 92,000 folks on the other end of that recent

barrageinformation-seeking mailer. It could have saved the deluge of calls the district has received fearing some sort of scam. (Apparently a deluge of calls is always a deluge, no matter how you parse it.) Wonder what they’ll call it if the foundation sends out a mailer actually asking for money rather than contact information? (Toledo Blade, 5/31/17)

- Academically-distressed Lorain City Schools has a chronic absenteeism problem, it appears. In the 2015-16 school year, more than 24 percent of students fit this description districtwide, despite the fact that the overall attendance rate for the district was 92.4 percent. In high school, it was more like 46 percent of students chronically absent. (I know, right?!) What did the district do for the 2016-17 school year to try and address this enormous problem? Implement a data tracking system that was, apparently, a failure. What is the district doing for the 2017-18 school year to try and address this enormous and previously-unaddressed problem? Communications (and another, hopefully better tracking system). According to this piece, the district wants to educate parents on what a child will miss, and how much less likely their child will be to graduate from high school and to launch a successful career if she misses too much school. “We want to create a positive relationship with the people we serve,” current district supe Jeff Graham said. “There is an education component for parenting.” I might humbly suggest the parents of Lorain already know what they’re missing. (Northern Ohio Morning Journal, 5/31/17)

- We end today with a little good news: the return of a community arts program for kids in Youngstown after a four year hiatus to regroup and relocate. There’s no info here on the programs offered and the audience to whom they are targeted, but I’m going to choose to stay in Goodnewsville and assume that the classes are high quality, the scheduling is amenable to a variety of work-life-school dynamics, the costs are low, and its doors are wide open. Feels good. (Youngstown Vindicator, 6/2/17)

The education reform movement is a big tent, which is particularly true when it comes to the idea of holding schools accountable for results. And, I would argue, the organizations that represent the extreme poles of that tent are the Thomas B. Fordham Institute on the right, and the Leadership Conference for Civil Rights on the left.

Within the tent are people and organizations who share important common views. One is that our massive, fragmented, highly bureaucratic education system is unlikely to make all of the tough decisions necessary to improve achievement without some pressure from the outside. Another is that the needs of disadvantaged kids are unlikely to be prioritized without a push, because their parents often lack political power in our school systems. A third is that properly designed testing and accountability systems can encourage positive behaviors in schools and school systems—positives that outweigh the legitimate negatives that come from testing.

But as is the case with any movement, those of us in this big tent disagree about a lot as well. One issue is whether it’s unwise, or morally essential, to set ambitious, perhaps utopian, goals for our education system. The following exchange, between the Leadership Conference’s Liz King and me, illustrates this divide. You might find it illuminating.

The relevant exchange begins at minute 27:00.

Mike Petrilli:

With all due respect Liz, what I worry about is that some of the groups have not learned some of the lessons from No Child Left Behind. I understand that your concern is that there are going to be schools that should be rated poorly, that get away with a high rating. And I get that. We should also be worried, though, about a system that labels every school as failing which is what we had by the end of the No Child Left Behind process. And what we could have if we're not careful about how we design these systems again.

If you have every school rated as failing because, for example you take literally the goal of “every kid college or career ready.” People, that ain't going to happen. Not going to happen in my lifetime. We’re at 30 percent, maybe 35 percent of kids right now college and career ready. We’re not getting to 100 percent unless we start lying about what it means to be college and career ready. Should we be aiming to boost those numbers? Absolutely. But if you literally build a system that says you're a failing school unless you get 100 percent of kids college and career ready every school is going to be a failure.

And what you're going to have is what we had back in 2009, 2010 where every school is a failing school and so no school is failing… Let’s make sure we don't go back to the day where we say every school in America is failing because we set these utopian goals in Washington and schools are not meeting them.

Liz King:

When we're talking about utopian goals we're talking about the goals that every parent has for their own child. Every parent puts their baby on the bus so that they go to school and learn what they need to learn to be proficient and to graduate high school on time and to be ready for college, career, and life. So that is the priority and the belief of every parent and I believe every educator goes to work every day with the intention that they are going to serve all of their children.

We no longer have a binary system. This is not you pass/fail, it is much more nuanced, and frankly a lot more complicated, but it is a much more nuanced system. We are unwilling to accept, we think it is a fallacy to view achievement gaps as inevitable or natural or preordained. This is a system we have created. We have created an inequitable system through policies and practices over the past several hundred years and we are working very hard now, many of us, to fix that. And that's the work that we need to be doing. It didn't start with NCLB and it didn't start with the civil rights movement. This work is much older than all of that. In the language that we use, we want an America as good as its ideals. We all believe in an education system which supports the success of all children. And that's the system we need to be working towards. So I think it is wrong to argue that our options are only to ignore historical differences, to sweep under the rug inequitable opportunities, and to look only at overall achievement.

Mike Petrilli:

But Liz that's not what I argued. What I’m saying is watch out for the utopian goals. Here in Washington, D.C., look at KIPP. We have a fantastic network of KIPP schools and because of universal preschool here they start at age 3. They have kids from age 3, they work with them until they go to college age 18. They spend a bazillion dollars a year, thanks to D.C.’s funding and also private fund-raising, and they do an amazing job. And they're getting great results. But we're still talking about, you know, I think the last data showed 50 percent of their kids graduating college. That’s five times better than the national average [for low-income students]. That’s amazing. That’s the best case scenario right now, I would argue, and we're at 50 percent. So I’m just saying that 100 percent, yes, aspirationally, rhetorically, that's great to aim for that. But we cannot bake that into accountability systems because I promise you that will result in virtually every school in the country failing and if that happens there will be no accountability.

The Colorado Legislature recently passed a bill that would allow charter schools access to the same local funding that traditional public schools in the state have long enjoyed. This bipartisan measure comes on the heels of a new national study by the University of Arkansas that found charters across the country receiving, on average, $5,721 less than nearby district schools in per-pupil funding.

The primary revenue culprit for this disparity? Local funding.

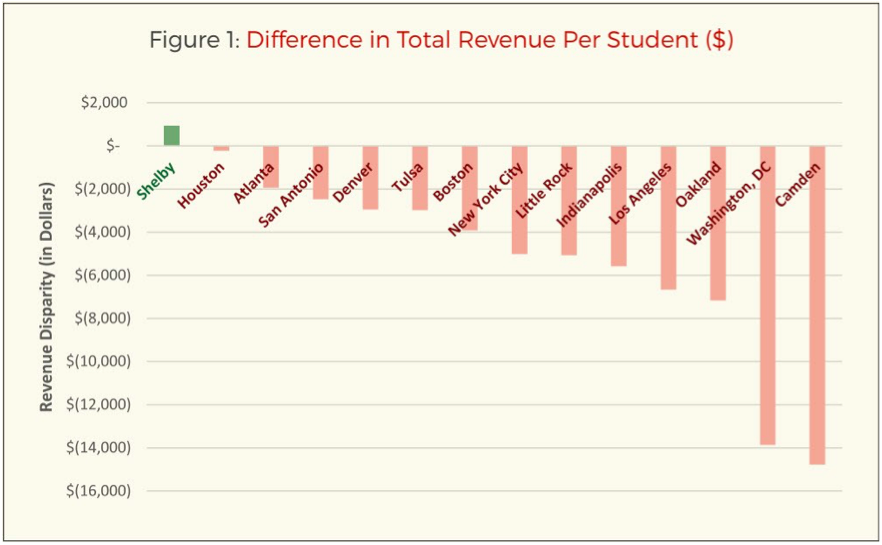

In doing this analysis, my colleagues and I examined funding for students in charters and district schools in fifteen metropolitan areas during the 2013–14 school year. As shown in Figure 1 (drawn from the report), in all but one of those locations, we found that children enrolled in public charter schools receive substantially less funding than those in district-operated schools. Across the country, that averages out to a shortfall of about 29 percent.

Source: Wolf, Maloney, May, and DeAngelis (2017). “Charter School Funding: Inequity in the City.” School Choice Demonstration Project, Department of Education Reform, University of Arkansas.

Critics of such analyses sometimes claim that funding disparities are due to differences in types of students, with district schools enrolling more students requiring additional educational resources. While the traditional schools in our study do enroll slightly more special needs children, these differences do not fully explain the funding gap.

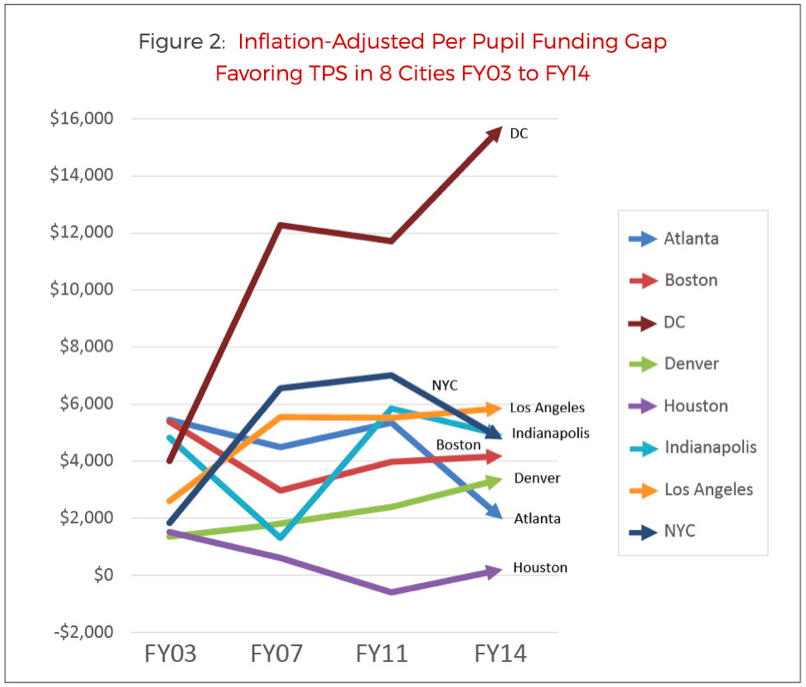

As shown in Figure 2 (also drawn from the report), that gap has widened with time. In the eight cities for which we had longitudinal data, the funding disparity had grown by about 79 percent over a span of eleven years.

Source: Wolf, Maloney, May, and DeAngelis (2017). “Charter School Funding: Inequity in the City.” School Choice Demonstration Project, Department of Education Reform, University of Arkansas.

Why does this funding inequity continue to exist? While funding formulas differ across states, most local education dollars are only allocated to district schools. When a parent opts out of a traditional public school and into a public charter, their children often lose every single penny of local education funding. In over half of the cities covered in our study, children attending public charter schools received zero dollars in local funding. If state legislators wish to remedy this inequity, they need to focus on allowing local funds to follow each child, regardless of which public school they select.

This new analysis is important for decision-makers to consider, especially if they care about improving student outcomes through efficiently allocating educational funding. Just imagine what would happen to the education sector if families could choose which public school to send their children to, with funds equitably following them to that institution. In an educational system where schools have the incentive to spend money productively, funding matters for improving student outcomes. Schools would be rewarded for quality and efficiency, freeing up the resources necessary to improve the lives of millions of children around the nation.

Corey A. DeAngelis is a Distinguished Doctoral Fellow and Ph.D. student in Education Policy at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville and a Policy Analyst at the Cato Institute. His research focuses on the effects of school choice programs on student achievement and non-academic outcomes.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

NOTE: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

The 2015 reauthorization of the federal Elementary and Secondary Education Act—known as the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA)—requires states to identify poorly performing public schools and help them improve. Importantly, ESSA grants states flexibility in fulfilling this requirement. That means Ohio has some decisions to make as it creates the state’s accountability plan due to the feds this fall. To inform this decision-making, the Ohio Department of Education commissioned Deven Carlson of the University of Oklahoma and me to use rigorous scientific methods to estimate the impact of recent efforts to turn around struggling schools in Ohio. I write to share the results of this study and to offer some general thoughts on how Ohio might proceed under ESSA.

Our study focused on two recent “school turnaround” initiatives: Ohio’s administration of the federal School Improvement Grant (SIG) program beginning in 2009 and its intervention in “priority schools” beginning in 2012. These programs targeted elementary and secondary schools ranked in the bottom 5 percent of eligible schools in terms of student proficiency rates in math and reading, as well as high schools with graduation rates below 60 percent. Importantly, both initiatives sought to produce rapid and lasting improvements in school quality by requiring significant changes to many aspects of schools’ educational delivery—particularly their leadership and staffing, as well as their use of data to drive instructional and managerial decision-making. These school turnaround efforts took three years to implement and entailed state-level monitoring and technical support.

There was one major difference between the programs, however: SIG was a competitive grant program for which districts applied, whereas the “priority school” program was mandatory and did not provide districts with financial support. Specifically, districts with SIG-eligible schools—those that fell below the performance threshold—could apply to receive up to $2 million in grants per school to support their implementation of one of SIG’s four models.[1] The “priority school” program, on the other hand, required all non-SIG schools below the performance threshold (i.e., those that did not previously apply for and receive SIG funds) to implement a school improvement plan without financial support.

The effects of these interventions were clear.[2] Ohio’s SIG efforts significantly improved student achievement in math and reading.[3] Indeed, the analysis indicates that students in schools that received SIG awards experienced achievement gains of around 0.10-0.15 standard deviations annually, which is the equivalent of approximately 60 extra “days of learning” each year if one assumes a 180-day school year. According to one estimate, by 2014, the average test scores of a SIG school’s students were around 0.55 standard deviations higher than they would have been without the intervention. That is the equivalent of students moving from the 5th percentile to approximately the 14th percentile on the achievement distribution.

Yet Ohio’s “priority school” interventions had no such impacts on achievement.[4] On average, the program’s requirements—such as staffing and leadership changes, data-driven decision-making procedures, increased community engagement, and the direction of Title I funds toward expanded learning time and professional development activities—did not have a positive impact on school quality as measured by student achievement gains on math and reading exams.

Why did student achievement improve in SIG schools but not in priority schools? We cannot say for sure. But the results of this study, as well as those of other rigorous evaluations, suggest some possibilities. In particular, research provides evidence consistent with the notion that managerial commitment and capacity, context, and disruption play important roles in the success of school turnaround efforts.

Managerial Commitment and Capacity

Turnaround initiatives are based on the notion that to improve the performance of a failing school, one must make fundamental changes across the entire organization—piecemeal efforts are inadequate for eradicating the entrenched perspectives and practices that lead to poor performance. In particular, the underlying theory suggests that fundamental change requires managerial commitment, resources, and managerial authority over key inputs, such as teachers.

The SIG program was more likely than the “priority school” model to meet these conditions. Districts applied for the program and selected from one of four improvement models, and ODE awarded grants based on a demonstrated commitment to implementing one of them. Additionally, the SIG program allocated up to $2 million per school, which ended up being over $2,000 per pupil for each of three years. The “priority school” effort, on the other hand, came with no additional dollars. Both the SIG and “priority school” programs featured technical assistance in the development and implementation of improvement plans, and both emphasized and facilitated school reconstitution through the replacement of teachers and principals. But SIG concentrated significant resources on a smaller set of schools in districts that were likely more committed to turnaround efforts.

Context

The problems plaguing poorly performing schools—and the available solutions to those problems—vary significantly across districts. Imposing uniform interventions across schools is unlikely to work. Consider school reconstitution. In the spirit of spurring fundamental and lasting organizational change, the SIG and “priority school” initiatives have emphasized the replacement of teachers and principals. This focus is understandable, as research convincingly demonstrates the importance of both (particularly teachers) in determining student achievement and longer-term outcomes. But the assumption underlying this strategy is that superior teachers and principals are available. In hard-to-staff rural and urban districts educating impoverished students—precisely those likely to be in the bottom 5 percent in terms of achievement-based metrics—school reconstitution could actually lead to inferior teachers and principals.

The SIG program featured voluntary participation and choice over which model to implement. Those districts that applied for and received SIG grants likely perceived the models they chose as viable in their particular contexts. They also were apt to view participation as worth the administrative burden that comes with state oversight. The “priority school” program was not voluntary—it was mandatory—and offered no such choice over intervention model, thus lowering the likelihood of a match between the improvement strategy and school context.

Disruption – For the Better

School turnarounds require fundamental organizational change. Such change is disruptive by design. On the one hand, research has shown that turnover among teachers and principals can have a negative impact on student achievement. On the other hand, as noted above, replacing a school’s teachers or principal may be worth it if their replacements are of sufficiently greater quality. In other words, organizational disruption is costly, so policy makers must make sure that the benefits of disruption are worth the costs.

Research that finds that turnaround strategies are successful also often finds that the more disruptive turnaround models were more likely to yield improvements in student learning (e.g., see this recent study). Our study also provides some suggestive evidence to this effect. For example, we found that the SIG Turnaround model was more disruptive than the SIG Transformation model, as it led to far more principal and teacher turnover. Yet there was also some evidence that the SIG Turnaround model led to somewhat greater improvements in student achievement. Thus, it seems that dramatic, fundamental changes may have been more efficacious than incremental changes for this particular set of schools. It’s also important to keep in mind, however, that the schools for which SIG Turnaround made sense were likely to be those that implemented it.

Concluding Thoughts

Our study enables us to say with relative confidence that, on average, Ohio schools benefited from SIG turnaround efforts but not from the first wave of “priority school” identification. It does not allow us to explain why that occurred with nearly that level of confidence. Nevertheless, in the context of a larger body of research, our results are consistent with some broad lessons. First, school improvement programs should ensure that school managers have the commitment and capacity (including money) to undertake reforms. Second, programs should be sufficiently flexible to accommodate the highly variable circumstances that districts face. Third, program designers should consider carefully both the risks and benefits of organizational disruption.

To the extent possible, Ohio might focus its resources toward a few of the lowest-performing schools whose districts demonstrate a commitment to fundamental change, and perhaps not waste state resources and impose administrative burdens on schools that see little value in implementing turnarounds. That strategy would allow districts—the locus of managerial authority and capacity at the local level—to implement significant reforms in schools that are most likely to change. For persistently low-performing schools that prove incapable of implementing meaningful changes, closure may be the only recourse for districts. As some studies from Ohio and elsewhere have indicated, shutting low-performing schools can have academic benefits if students transfer to better schools. (Also see this study for particularly rigorous evidence of closure’s potential effectiveness.)

Ohio policymakers also should keep in mind that one purpose of accountability systems is to capitalize on the expertise of local managers—to provide them with the authority and capacity to take actions appropriate given their local context. Although micromanagement is always tempting—and there is evidence that specific interventions such as data-driven decision-making and extended instructional time can be very effective—the powerful logic of accountability systems is that schools should be held accountable for outcomes, as opposed to the means by which they generate those outcomes.

Stéphane Lavertu is an associate professor in the John Glenn College of Public Affairs at The Ohio State University. The opinions and recommendations presented in this editorial are those of the author and do not necessarily represent policy positions or views of either the John Glenn College of Public Affairs or the Ohio State University.

[1] Districts could close a school, “restart” a school under independent management, or implement turnaround models (called SIG Turnaround and SIG Transformation). Nearly all districts chose to implement the turnaround models.

[2] The study focused on student achievement in math and reading and graduation rates because those were the target areas of these programs. We emphasize the achievement results here because they were a more central part of our study.

[3] The impact on graduation rates was also positive, but we examined just a subset of high schools that received the grants.

[4] There appeared to be some modest positive effects on graduation rates, but we examined just a subset of high schools.

Editor’s note: The following video features a panel at the 70th Education Writers Association National Seminar that took place on Wednesday, May 31, in Washington D.C. Titled “Accountability and ESSA: Where Are States Headed?,” it featured Linda Darling-Hammond, President and CEO of the Learning Policy Institute; Liz King, Senior Policy Analyst and Director of Education Policy of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights; Chris Minnich, Executive Director of the Council of State School Officers; and Michael Petrilli, President of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. Caitlin Emma, an education reporter for Politico, moderated. Click the image below to watch.

Today’s colleges of education generally do a good job prepping new teachers for the traditional classroom. For teaching students outside the mainstream, the training is less robust. At least, that’s what Alison Alowonle discovered when she stepped into her first student-teaching job in a gifted ed magnet school thirteen years ago and fell in love with the students.

When she moved to a classroom of her own, she started small, clustering increasing numbers of gifted students each year before designing her own pullout program at Excelsior Elementary in Minnetonka, Minnesota, picking up a certificate in gifted education along the way. This year she was one of eleven finalists for her state’s 2017 Teacher of the Year award.

“Gifted” is a label that’s often difficult to quantify, but there’s little doubt Alowonle’s elementary students are exceptional. To qualify for her class, students must demonstrate an IQ upward of 140 and pass through a simulation designed to test their intellect. But intelligence alone is not what makes them unique. According to Alowonle, her students also exhibit high levels of inward motivation and drive; “intensity” is one of her favorite words to describe it.

Here, Alowonle shares her recommendations for engaging gifted students.

Q: How does your “looping” model of teaching work?

I teach students for two years in a row. My homeroom is fourth- and fifth-graders: twenty-one students, a mix of boys and girls who are together two years. It’s nice because the fifth-graders are really the mentors, and then the next year the fourth-graders loop around and get to take on that role. It’s a really great chance for them to grow in leadership. What’s nice about that looping piece is that you can hit the ground running. You know half your students already at the start of the year. They know the rules and they can help teach the new kids. You don’t have to spend a lot of time in that “getting to know you” phase. We get a lot more instructional time that way, too.

There are kids here who have been ostracized or isolated as gifted children, and they come here and suddenly they’re with like-minded peers. They feel comfortable to talk about things they’re interested in, and not be met with confusion or be laughed at. They feel like they can be themselves.

They are very diverse in their interests and personalities. There are a lot of athletic kids and others who don’t even go near athletics. The one common area they have is their intensity. A psychomotor intensity, rapid speech, creative intensity, imaginational. They’re all very intense in their own way, and then they’re brought together in that commonality.

We do a lot around the whole child, the social-emotional learning. For instance, during the first few weeks of school, we talk about executive functioning. We look at the brain and why we react the way we do emotionally, and how we can calm ourselves when we’re in a state of fight-or-flight. My students are unique in their intensities and emotions.

Q: Are there any other ways you’d say your students are in any ways different from those in a traditional classroom?

They are similar in many ways. Just like most classrooms, I have kids who are calm and can sit all day and don’t need to say “look at me,” and then there are others who can’t stop moving or talking.

However, the child in my class who is quiet is usually very intense on the inside. They go deep in their thinking and are quick-processing for the most part. Instead of needing five examples of something before moving to the application phase, they might need only two examples, or even just one. The pacing between this and a regular class is very different. It’s very speedy. There’s not a lot of “sit and get.”

Q: Taking all that into consideration, how do you typically organize lessons?

It’s a lot of project-based learning here. For instance, in chemistry we’ll work on learning the properties of atoms and bonds and we’ll go through the whole chemistry unit, but then it’s peppered throughout with different labs they can do. At the end of a unit, they complete an individual project where they can ask themselves, “What do I want to do with this?” They can do some experimenting at home, or in the classroom. The only criteria I have is to incorporate something from the unit and then go deep with it.

Q: How do you grade and assess students of this caliber? Are they naturally competitive?

Yes, they are competitive. They all like to do well and they’re close-knit. It’s very much like a family. There’s a lot of encouraging, but also some competition. We use Marzano’s rubric, a 0–4 scale, which is really great for kids in general but especially for gifted kids.

If you get a three, we’re saying, “You got it. You picked up what I was throwing down.” Anything above that is where you have a chance to go above and beyond and do something I haven’t taught you with it. Maybe one of the literature assignments I’ll give is to take the protagonist and tell three of their character traits and find evidence in the story as to why these character traits are true to this character. If they pick their three traits and they give evidence, you get the three. But if a child goes through and doesn’t just cite pages but uses direct quotes, and I haven’t taught that it would get them a 3.5 or a 4. It allows them the opportunity to reach and figure out what can they can do above and beyond.

Q: You spend a lot of your time working not only with kids but with their families as well. What does that entail?

The family is super important. That’s a huge component for me. I think the most important thing is to almost over-communicate things. I send out a very detailed weekly newsletter about what it looks like to be a child in this room for a week. I write down what we’ve been doing each day, in each subject, each project. Especially because a lot of students struggle with executive functioning, planning, and meeting deadlines. I lay it out for the parents: Here’s what you might want to be asking the child. Here’s something you can do at home to extend the learning going on the classroom. It’s very helpful.

I’ll also send periodic emails to check in with parents to let them know how things are going. I always try to touch on the positives, which is something they’re not always used to. I’ve had responses from parents saying: “I’m really surprised by your email. I thought this was going to be another email about how my child was sent home today,” because their child has had difficulties in the past. I’m not talking about all the students in my class, but there are definitely those who have been a round peg in a square hole, and school has been hard for them. As a parent, conferences aren’t going to be the most fun to go to. Your child is constantly off task, or reading a book instead of paying attention.

I think, as a parent, ‘What would I want to know?’ I would like to know some anecdotal information about how my son is doing. If you put yourself in those parents’ shoes and ask, “What kind of relationship would I want with that teacher?” That’s what I try to put forth.

Q: Do you have any advice for teachers looking to learn more about gifted ed or move into that space?

I think it’s important to get some sort of education yourself. I have my gifted education certificate. Those classes were really helpful for me. The training you get in college is really skimpy. Gifted ed is actually grouped in with special ed. I’ve even gotten out my old college textbook and there’s one paragraph in there on gifted kids. Things have changed now, though: you can get your master’s in gifted ed and there are staff development opportunities.

But you also need to get hands-on experience. If you’re a regular third-grade teacher and you have a gifted program in your school, get to know that gifted ed teacher. Pop in during your prep or lunch time and see what’s going on. It’s a great opportunity to get to know these unique individuals.

Stephen Noonoo is a freelance writer, editor, and ed tech consultant. You can find him on Twitter at @stephenoonoo.

Editor’s note. This article originally appeared in a slightly different form on GettingSmart.com.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

A new report seeks to probe the impact of state takeovers of entire low performing districts—which don’t occur often and therefore have a limited evidence base. Analysts examined the results of one such takeover in Lawrence, Massachusetts, a midsized industrial city thirty miles north of Boston that is rife with deep poverty and whose primary school district includes roughly 80 percent of students who are English language learners.

The district enrolled approximately 13,000 students in twenty-eight schools in fall 2011, when the Massachusetts Board of Elementary and Secondary Education classified Lawrence Public Schools (LPS) as a “level 5” district, the lowest rating in the state’s accountability system, and placed it into receivership. The receiver, a former Boston Public Schools deputy superintendent, took over in 2012 and was granted broad discretion to—inter alia—alter the teachers’ collective bargaining agreement, require staff to reapply for their positions, and extend the school day or year.

The turnaround strategy had five major components: 1) setting ambitious performance targets; 2) increasing school autonomy by reducing spending on the central office by $6.6 million in the first two years, pushing funds down to the school level, and providing different levels of autonomy and support based on each school’s prior performance and capacity; 3) staffing changes, which led to more than half the principals being replaced in two years and the lowest performing teachers also being let go (8 percent were removed or fired, but resignations and retirements brought that to one third being replaced, many by Teach For America corps members); 4) teaching teachers how to use data to drive instruction; and 5) increasing learning time via things like “Acceleration Academies,” which are intense, small-group tutoring programs offered during winter and spring breaks, with student participants selected by their principals, and outstanding teachers deployed (from within and beyond Lawrence) through a competitive process.

Analysts examine impacts in the first two years of the turnaround. They use as a comparison group student level data from across the state for 2006 to 2015, focusing most of their analysis on one fourth of those students who attend the poorest districts. They examine changes over time in individual students, seeking trends before and after the turnaround and comparing LPS to demographically similar districts not subject to turnaround. They find sizable impacts on math achievement; for instance, by year two, the turnaround had improved LPS math scores by 0.29 standard deviations when compared with kindred districts. Yet the ELA impact ranged only from 0.02–0.07 SD. English language learners saw particularly large gains in math in both years, as well as moderate ELA gains. The gains were more pronounced in the elementary and middle schools, less so in high school.

Though a selection effect is obviously present in the Acceleration Academies, their most rigorous analytic models nonetheless suggest that these weeklong tutoring sessions were an important factor in the turnaround’s success. Yet analysts found scant evidence that the turnaround affected other outcomes like attendance or the probabilities of (a) remaining in the same district, (b) staying in school, and (c) graduating in twelfth grade, compared to comparison districts.

Three quick takeaways: these are fairly encouraging results for a state turnaround, so we’ll be curious to see if they persist beyond the first two years; ditto on whether similar success can be replicated elsewhere (made more likely if states take on one district turnaround and not multiple); finally, the positive evidence continues to mount (here, here, and here, too) that individual or small-group tutoring is advantageous for struggling students, so let’s continue to find ways to bring it to scale.

SOURCE: Beth E. Schueler et al., “Can states take over and turn around school districts? Evidence from Lawrence, Massachusetts,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis (January 2017).

A short new report by A+ Colorado evaluates the recent gains of Denver Public Schools (DPS) in a way that education leaders elsewhere might beneficially heed.

First, we see that more DPS students met grade level proficiency for Math and ELA in 2016 than in 2015. Then the authors list the highest achieving schools, as well as those schools that made the biggest jumps in proficiency rates. A scatter plot shows a demographic index and elementary school ELA proficiency rates. Here the serious thinking begins.

We see that a large number of DPS schools are besting their peers around the state with comparable demographics. This doesn’t necessarily mean they’re doing great. For example, Knapp Elementary, a district-run school, had fewer than 35 percent of its students read and write at grade level, yet it’s far above the state average for schools with similar concentrations of poor and multilingual students. Knapp also makes the podium when the authors rank schools by growth rates.

The authors conclude by showing the rate at which Denver needs to improve to meet its 2020 goals, and we see how much heavy lifting lies ahead. From 2015 to 2016, DPS increased the number of third graders proficient in ELA by +3 percentage points, but it would have to improve by +12 percentage points per year from here on out to get to where it says it wants to be in 2020. Faced with that kind of challenge, some might give up on the goal. Others might dig into the data and find the best ways to move forward. For those who plan to keep improving, this report is a great place to start.

SOURCE: “Start with the Facts: Denver Public Schools,” A+ Colorado (May 2017).