- I was remiss in not clipping this piece from the massive “CBus Next” education package in the Dispatch last week. It is about “the future of education” and talks a lot about technology – robots, combining science with art and history classes, virtual reality, etc. That well known advocate of MOOCs and online course choice Aaron Churchill is quoted within, which is important. But as a side not: don’t a couple of those schools featured in here sounds really cool? I really think so, but I could be biased. (Columbus Dispatch, 9/22/17)

- Speaking of online education, ECOT this week cleared the first hurdle toward its regeneration as a dropout recovery school as the Ohio Department of Educated accepted its report that the majority of its students are in need of a special program for at-risk students. (Cleveland Plain Dealer, 9/26/17)

- And speaking of alternatives to the status quo, let’s not forget the original “opt out”: homeschooling, which is still a sizeable slice of the education pie here in Ohio. And it’s gotten more sophisticated too: with “homeschool cooperatives” evolving to provide unique experiences for students and families well beyond the kitchen table. Take a look at the Red Oak Community School (unfortunate name choice, I know, but they’re working on that), one such co-op for children ages 5 to 11 that has been around for years and continues to grow. Its self-directed, back-to-nature bent seems quite popular. (Columbus Dispatch, 9/26/17)

- You will be pleased to know that the Mystery of the Bungled Broadcast of last week’s state board of education meeting has been solved. It was simple technology access issues and miscommunication thereof. Jinkies, I would have bet a Scooby snack that it was The Miner 49er. One bit of additional good news: those technology issues might not be resolved for another couple months. (Cleveland Plain Dealer, 9/25/17)

- Anyone remember the dour-looking gathering of school district superintendents at the Statehouse last year, escrying the “graduation apocalypse” facing their students in the Class of 2018 due to an increase in graduation requirements? Me neither, but it is a fond memory for the superintendent of tiny Shadyside Schools in Belmont County. That’s because he claims credit for making it happen and for the one-year moratorium on those requirements currently enjoyed by every student in the Class of 2018 which happened afterward. He and the other supes said an alternative to the requirements was needed because the Class of 2018 had not had enough time to acclimate to the new End of Course exams and that they shouldn’t be denied a diploma if that lack of familiarity led to low performance. As some folks suspected, however, a one year moratorium was not enough for the Supes of Doom. In this piece, Shadyside’s supe laments that “no action has been taken by the state to assist current juniors”, who of course have had an additional year to acclimate to the “new” tests. And he is girding his loins for the fight to extend the moratorium. Where does it end, I ask you? (Well, we all know.) The irony here is that this story appeared on the news site of a TV station in nearby Steubenville, Ohio. The local school district in Steubenville had three of its buildings receive an A grade in both student growth and test-based proficiency this year, placing it in rarefied company with high-wealth suburban schools. While it likely took a ton of work for Steubenville to manage this success, I wonder why it didn’t occur to Shadyside to give that a whirl first before storming the Statehouse barricades and changing the entire state’s accountability system? (WTOV-TV, Steubenville, 9/25/17)

- Some recent news from Youngstown: District CEO Krish Mohip is reporting some impressive academic improvements for kids participating in the new after school program introduced in the last five months of the previous school year. He has high expectations for more of the same with the first full-year version of the expanded program. (WFMJ-TV, Youngstown, 9/25/17) Meanwhile, this week saw the first meeting of the district’s Citizen’s Coalition to advise the CEO. Seems pretty encouraging from this report, but do recall that some folks are not keen on this arrangement. (WKBN-TV, Youngstown, 9/25/17) Speaking of those not-so-keen folks, they had a meeting this week. At it, they passed a petty resolution directed at an entity which has no power over any corner of state government. And for good measure, their resolution was worded so as to apply to districts other than Youngstown. Kudos are in order for the sheer scope of this sad lesson in futility. (Youngstown Vindicator, 9/27/17)

- Finally today, closure for a story that we first clipped back in the early summer, but whose roots (see what I did there?) reach back more than a year. A Toledo City Schools floriculture teacher was fired for giving away plants the district said were their valuable property. She had been suspended with pay for more than a year while the disciplinary process played out slower than watching grass grow. (Toledo Blade, 9/26/17)

This study uses administrative data and other public records to examine the impact of unionization on the test-based achievement of California charter schools between 2003 and 2013. Using a difference-in-differences approach, the authors estimate that unionization boosted math achievement by about 0.2 standard deviations but did not significantly affect reading achievement. These estimates differ from those of Hart and Sojourner (2015), who analyzed similar data but found that unionization had no impact on test scores. However, in the appendix of the more recent study, the authors provide a mostly convincing defense of their methodological choices.

A quarter of California charters were unionized in 2013, and between them these schools accounted for a third of charter enrollment. However, for obvious reasons, the authors exclude “conversion” charters that are automatically unionized because they are legally bound to the district contract. So their analytic sample includes just forty-four charter schools that switched from non-unionized to unionized between 2003 and 2013.

Overall, students in unionized charters score about 0.5 standard deviations higher on math and about 0.3 standard deviations higher in reading than students in non-unionized charter schools. And teachers in these schools are more experienced and far more likely to be on track for tenure than those in non-unionized charters. Yet relative to non-unionized charters, “switchers” have lower test scores, more minority and English Language Learner students, and are unusually concentrated in large urban school districts. (Nearly half are located in Los Angeles, Oakland, and San Diego.)

As the authors note, unions might improve school performance in a number of ways. For example, they might attract better teachers (via higher wages), reduce teacher turnover, and boost “teacher voice” (thereby improving the flow of information within a school). However, they might also do harm insofar as they prevent administrators from rewarding high-performing teachers or terminating underperforming teachers, and insofar as they engage in rent-seeking behavior.

But this is just speculation; one weakness of the study is its inability to account for the mechanism through which unions may boost achievement. For example, the authors estimate that unionization leads to a 0.8 year decline in teacher experience but has no effect on class size, the share of teachers with a master’s degree, or the fraction with a tenure-track position (none of which makes very much sense).

Another major question mark is the degree to which the study’s findings are generalizable. After all, unionization doesn’t occur in a vacuum. So it’s possible—perhaps even likely—that working conditions and administrators at the schools in question were below average. Thus, even if the authors have succeeded in isolating the impact of unionization for these schools, it doesn’t necessarily follow that every charter would be higher-performing if it unionized.

In short, the study suggests that voluntary unionization is potentially beneficial for low-performing charters. However, when it comes to high-performing charters—not to mention traditional public schools, where both theory and experience suggest that unionization may be more problematic—there are still plenty of reasons to be skeptical.

SOURCE: Jordan D.Matsudaira and RichardPatterson, “Teachers’ Unions and School Performance: Evidence from California Charter Schools,” Economics of Education Review (September 2017).

“We shall have to build the schoolhouse first and the church afterward. In our age, the question of education is the question of the church.” – Archbishop “Dagger John” Hughes

John Joseph Hughes was a feisty Irish immigrant who became the first Catholic Archbishop of New York. If you have seen the film “Gangs of New York,” you have a sense of the city in which he charted a course for the Catholic church, with the explicit purpose of helping immigrants find their way in their new home.

I say “feisty” because, like many of the scrappy Catholic school teachers and leaders we work with today, he was exactly that. One account described Dagger John as: “Unsystematic, disorganized, impulsively charitable, unable to keep his checkbook balanced, vain enough to wear a toupee over his baldness, and combative.” He became “the best known, if not exactly the best loved, Catholic bishop in the country."

Yet, Archbishop Hughes’s “dagger” was not only his sharp personality, but also his unwavering belief in the transformative power of Catholic schools. He faced fights from the legislature, from “nativist” mobs who attacked him and ransacked his home. But he always stayed true to his belief that Catholic schools could change history—particularly for the immigrant communities they grew to serve.

New York City’s Partnerships Schools (PNYC), the network of Catholic Schools I have the honor to lead as superintendent, strive to walk along the path Dagger John forged. We are equally unwavering in our belief that Catholic schools have the power to change history today, just as they did more than 150 years ago when they were created. Yet, this era is different. Today, the legislatures aren’t the ones trying to close us, but others are trying to outcompete us. The environment is cutthroat, and we have to fight for what we’ve got. And the rules aren’t always fair.

But we have the unique opportunity to show everyone who’s ready to eulogize Catholic schools that they’re wrong to underestimate the power and potential of faith and values in an era of increased competition and academic rigor.

And this year at PNYC, our scrappy band of troublemaking leaders is celebrating its fifth year as a trailblazing network of high performing, faith-filled urban Catholic schools. We aim not for comfortable conversations about the decline of Catholic education in America but to shake the world awake to the possibility for a thriving system of schools in this new century.

As we launch our fifth year together as a network, we are reflecting on the performance of our schools, the community we are building, the need for perseverance in the face of setbacks and possibility for truly breakthrough results.

Performance

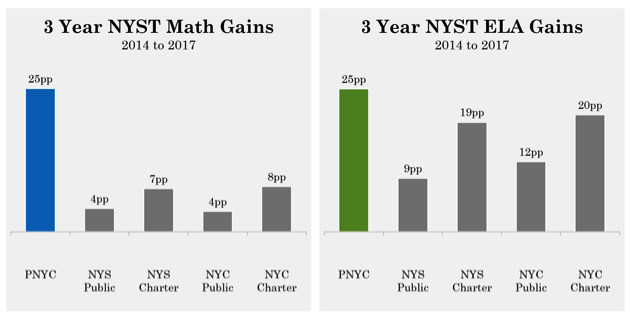

In 2014, our schools lagged significantly behind their charter and public school peers when it came to achievement on the New York State test. After three straight years of achievement gains, our school’s ELA results are on par with or better than all but a few of the city’s highest performing charter networks.

What’s more, our network-wide achievement in both ELA and math has jumped 25 percentage points since 2014. And that means that our students are now beating the average state, city, and New York charter school averages in both core content areas.

While these gains are exciting, they are not what make me most proud and energized about our work. At the end of last year, we began to track our progress across a host of indicators that matter most to us—things like Catholic identity, community, character, and more. We found that fully 95 percent of our teachers and leaders believe that our core values drive everything we do, feel that our schools emphasize the importance of religious instruction and faith formation, and look forward to coming to school each day.

Anyone who has ever been to one of our schools can attest to this. Last year, we had a high performing leader from Success Academy visit one of our schools. At the end of her visit, she turned to Kathleen Quirk, our chief of staff, and said, “your schools are magical.” (I hasten to add: That leader joined our team as an academic dean the same day.)

She’s right, too. There is a magic that happens when you weave together faith, a relentless focus on academic excellence, and an unapologetic focus on character- and values-driven education. And we are confident that our faith, the strength of our communities, and the warmth and love our students feel each day change their lives at least as much as the academic work we do. Probably more.

Perseverance

At the same time, we can always do more. Even this year, while we had much to celebrate, we see areas for growth. Our scores dipped slightly in math. We value all of this information—the good and the bad. Because we understand that we see our students better and we can serve them better when we know where they are across a host of indicators.

Yet, any stagnation is concerning, because we also know that the forces working against Catholic schools in general and urban Catholic schools in particular are real. There are too many people in the education world who have decided that urban Catholic education is dead. And their conversation is not about how to preserve our legacy, but rather about how sad they’re going to be at the funeral.

And this year more than ever, our schools and this network exists to help say: Not on our watch.

Possibility

As we embark on our fifth—perhaps our most important year—we draw a lesson from Samuel Pierpont Langley.

Few people know Langley’s story—I didn’t until recently. Langley was a scientist who wanted to invent a “flying machine.” And he had every advantage. He was given $50,000 by the War Department to support his work. He was a professor at Harvard, and he worked at the Smithsonian. He had the wherewithal to find and hire the “best” minds that money could find.

That is to say: Langley was well set up for success. In fact, people were so convinced he was going to succeed that the New York Times followed him around to document what they thought was history in the making. But, with every advantage money and influence could buy, why have none of us heard of Langley?

It’s because at the same time, a much smaller and scrappier effort was underway in Dayton, Ohio, where two brothers—owners of a local bicycle shop—were pursuing the same goal. They had none of the advantages Langley had. They had no money except what they earned at the bike shop. Nobody on their team had even a college degree. And the New York Times never followed them anywhere. Nobody thought they were making history.

Instead, they had the unwavering belief that they would succeed. And with that, they attracted a scrappy team who was just as crazy as they were. Every time they left for work in the morning, they had to take five sets of parts with them. Because that’s how many times they would crash each day before dinner. But the crashes didn’t stop them; they did take flight on December 17, 1903. And while no one was there to experience it, everyone knows that this scrappy band of misfits changed history.

And do you know what Langley did when he found out? He quit. That’s how little he believed in what he was doing.

And so, as I look at the ups and downs I know we’ll face over the years, I don’t worry. Those crashes are just opportunities to learn and grow.

Instead, I remember what we’re here for.

We are here because we believe that the Catholic church in general and Catholic schools in particular have been one of the single most important poverty elimination programs in the history of our nation. We are here because we believe that students are best served in an environment where you can unapologetically weave together faith, academic excellence, and service to form students into young men and women for others.

And we are here because we stand on the shoulders of the giants who have come before us—leaders who overcame serious obstacles because they had an unwavering belief in the transformative power of Catholic schools.

And those founders faced at least as many challenges as we do now. Such was the faith and the hubris of our founders. We have the privilege of teaching kids in schools that wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for them.

And so, when I think about where we have to go—the obstacles I know we face and the very real challenge to demonstrate learning dramatic learning gains that are worthy of the students we serve, I can’t help but be inspired by the scrappy and daring founders of our network of schools. As everyone else follows our charter peers around the way the New York Times followed Langley, I can’t help but smile. Because in our age, as in Dagger John’s, we know the future of Catholic education is the future of the Church. And that belief will power us forward until this new era of Catholic education takes flight.

Kathleen Porter-Magee is the Superintendent and Chief Academic Officer of Partnership Schools.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

You have no doubt seen numerous media stories regarding the recent release of school report card data in Ohio. As supporters of a robust accountability system, we urge you to pay attention to the stories and the ongoing discussion. The success of our public schools (charter and district) in doing the vital work with which they are entrusted must be assessed, reported, and analyzed. Schools which evidence success should be lauded, emulated, and expanded to reach as many students as possible. Schools which struggle in any area should be highlighted and helped to improve if possible.

None of these things can happen without robust data and clear-eyed analysis.

Fordham has worked for many years to be a source of unbiased analysis, research, and commentary on the state’s annual report card data. With Ohio’s most recent data release having occurred in mid-September, we have published the following:

- A look at trends from previous years to which the new data will add depth

- A detailed look at the difference in comparison parameters for charter and district school analysis

- A first-look overview within hours of the data becoming available

- The first comparison between charter and district schools in Ohio’s eight largest urban centers

Additionally, Fordham staff contributed to media reporting on the data from the Cleveland Plain Dealer, the Dayton Daily News, and statewide public media via radio and television, among others.

In the coming weeks, we will be recommending improvements to the state’s report cards to help parents and the public make better use of the vital data.

Keep an eye on our Ohio Gadfly Daily blog, or sign up here to receive our biweekly e-newsletter so you won’t miss a thing. It’s too important not to stay in the loop.

- Two separate stories; a similar theme. That theme is the correlation between test scores and race/income as reflected in state report card data. First up, Aaron is quoted on that topic in the Dispatch. (Columbus Dispatch, 9/24/17) Next up, Chad is quoted on that topic at length on statewide public television. (State of Ohio, via Ideastream Public Media, 9/22/17) Well, now that we’re all agreed (thanks to the data that we have at hand), on with the solutions, right?

- We interrupt your regularly-scheduled report card data update to bring you this “news”: the Ohio Department of Education isn’t currently planning to change its process for verifying students’ “at-risk” status despite the fact that ECOT will soon be entering into said process. Chad is on hand to suggest that if this is a problem for folks (well duh), the legislature may want to consider inducing a change. (Columbus Dispatch, 9/23/17)

- Returning to report card-related pieces, editors in Youngstown this weekend opined upon the district’s still-dismal report card and how that may affect their support for the CEO. Ouch. (Youngstown Vindicator, 9/24/17) You will note that despite their angst (perhaps understandable given that the CEO’s “latitude” will grow with each year of continued poor performance in the district), the Vindy editors do not reject the report card data. What would such a rejection look like? I’m glad you asked. Despite a pretty darn good overall report card for his district, Olmsted Falls’ supe today completely rejected the state’s entire report card structure over a handful of less-than-sterling indicators for his district. He promises to create his own “report card” forthwith to “accurately” describe the place. Because those aforementioned indicators aren’t true? Or are just problematic? (Cleveland Plain Dealer, 9/25/17)

- Menlo Park Academy, Ohio’s only charter school for gifted students, began the school year in its new location – a renovation of an old factory on Cleveland’s West Side. Here’s a quick overview of the project along with some very colorful photographs. Looks like a great new space for a great school. (Cleveland Plain Dealer, 9/22/17)

- Following up from last week’s Dads Walk their Kids to School Day, guest columnist Allen Smith (director of operations for the Boys and Girls Clubs of Cleveland) opines on the importance of men fully embracing fatherhood and all that it requires of them. Couldn’t agree more myself. (Cleveland Plain Dealer, 9/24/17)

- A sad situation in Akron as a private school serving mostly students with disabilities suddenly curtailed services last week with little notice. At issue appears to be a cash flow problem stemming from a change in the payment process for students on the state’s Autism Scholarship Program. Hopefully this can be resolved quickly in the best interests of students and families. (Akron Beacon Journal, 9/24/17)

- The divisive teachers strike in Louisville, Ohio, may have ended 10 months ago, but as my dedicated Gadfly Bites subscribers will know, the repercussions have continued due to accusations of data tampering against 10 striking teachers and the ongoing tussles between the teachers and the district over those accusations. Two settlements approved last week may, however, be the beginning of the end. In one, the last of the accused teachers still technically on staff in Louisville agreed to leave and to pursue no litigation on the matter in exchange for a sick time payout and a reciprocal agreement of no litigation on the district’s side. In the second, the state teachers union agreed to pay Louisville $75,000 for no explained reason and both sides agreed to that “no litigation” thing. I’ll let you read the piece to learn why the state teachers union is involved in this. I’ll just say kudos to the Rep for getting the details and ask if someone could please call up Mike Antonucci. I think he’d be interested in this. (Canton Repository, 9/22/17)

NOTE: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

The recent request by the Electronic Classroom of Tomorrow (ECOT) to apply for Ohio’s Drop Out Prevention and Recovery (DOPR) designation has shined a spotlight on this unique type of alternative school and has created many misconceptions surrounding what they do, the students they serve, and how they serve them.

Those of us who have dedicated our careers to providing safe, inclusive, high-quality learning environments for our most challenged students think these misconceptions should be identified and exposed. DOPR is a status for which schools must apply and is outlined in state law. The designation has existed for many years. Only programs that meet the components set forth by law are approved by the Department of Education. DOPR schools must meet specified academic as well as financial objectives set by the Department. The designation is not a shelter for charter schools to utilize as a protection against public accountability for student performance, nor are drop out recovery waivers intended to be leveraged by schools not specializing in this specific student population. The designation is meant to provide an alternative system by which to gauge the successes of schools serving nontraditional students—those who by virtue of their life circumstances and past educational attainment are fundamentally different from students served in traditional high schools. These students’ educational gains are difficult to measure by traditional report metrics.

DOPR schools are a vital component of Ohio’s education landscape and have had great success with students who historically have not been served well by traditional educational models. National statistics show that over 1.2 million students drop out of high school each year in the United States alone, which is about 7,000 a day or about one student every 26 seconds. These students often face innumerable barriers to obtaining their high school diploma. These obstacles include teen pregnancy, incarceration and other problems with the law, full-time employment in order to financially support their families, health problems, expulsion, and other personal reasons. Many of them are several years behind their grade level, creating added urgency as well as challenges for students and the schools serving them.

An abundance of research shows that without a high school diploma, students have greatly reduced chances of success, and the costs to society are great. High school dropouts in the U.S. commit about 75 percent of crimes and earn on average $200,000 less income over their lifetime than those who obtain their high school diploma. Dropout recovery schools provide the specialization and expertise necessary to assist students who have fallen far behind their peers and help prevent students from falling through the cracks and failing to reach their full potential.

The vast majority of Ohio’s DOPR schools are located in brick-and-mortar buildings and do not serve students exclusively online, which many dropout recovery leaders/educators feel greatly contributes to their success. Every child converted from dropout to recovery creates a net economic gain of at least $292,000 between additional wages earned and the costs of social and legal services saved, not to mention the significant improvement of quality of life. The benefit to society is overwhelmingly positive.

Dropout recovery high schools are the last line of defense in serving our state’s most challenged students. The positive outcomes that these students receive through dropout recovery programs must not be eclipsed by the recent request, nor should the designation be used solely to evade closure. That would dilute the good work that is being done by DOPR schools across the state of Ohio and nationally.

Cris Gulacy-Worrel currently serves as Vice President of National Expansion for Learn4Life Concept Charter Schools, a non-profit charter management organization that manages schools serving over 30,000 students in several states, including Ohio's Flex High School.

- More on state report cards to start the day. To wit: at least one state legislator is very very unhappy about state report cards, for reasons which are barely articulated in this piece. He’s got some support among the usual statewide public media interviewee pool. Fordham is namechecked in this piece as well, regarding charter school report card data. (WOSU-FM, Columbus, 9/22/17) Fordham is namechecked at the very end of this piece as having supported a “solution” two years ago to what is apparently a longstanding “problem” regarding charter school sponsor payments. Why mention that now? That “problem” is now seen as one of a couple of “loopholes” which might “benefit” ECOT (pronounced “not stop them”) in its efforts to regenerate into a dropout recovery school. And you know how journalists hate loopholes. (Cleveland Plain Dealer, 9/21/17)

- The Columbus Dispatch has been publishing a monthly series on “The Future” of our great city, looking at various areas of civic endeavor and looking at what’s next within those areas in some depth. They have reached the topic of education this month, and one of the voices talking about “what’s next” is United Schools Network CEO Andy Boy. Great interview with an important but often overlooked civic champion. (Columbus Dispatch, 9/22/17)

- A brand new school has opened in Cleveland this year. It is a K-8 feeder for the popular IB-based Campus International High School in partnership with Cleveland State University and CMSD. Sounds awesome. Have a great year, everyone! (Cleveland Plain Dealer, 9/20/17)

- 2017 marks 20 years since the landmark DeRolph court decision regarding school funding in Ohio. And that is the only unvarnished fact you will likely learn in this piece shaped largely by the folks interviewed within it. All add their own layer of varnish to the story. (Columbus Dispatch, 9/22/17)

- We end today with a topic near and dear to my heart: dads. Yesterday was the seventh annual Fathers Walk Your Child to School Day in Stark County. A record 33 schools took part and more than 1,800 fathers walked 2,200 students to school countywide. There are lovely photos to go with this piece. You should look at them. (Canton Repository, 9/21/17)

Teenagers declaring “I’m bored” is as timeless as a John Hughes film, but may mask a serious problem: Among high school students who consider dropping out, approximately 50 percent cite a lack of engagement with school as a primary reason, and 42 percent report that they don’t see value in the work they are asked to do. In a recent Fordham study, What Teens Want: A National Survey of High School Student Engagement, we found that many students are not being served effectively by the traditional “one size fits all” comprehensive high school. At the same time, there’s growing support for giving adolescents more educational choices.

To explore what keeps these schools from proliferating and how obstacles can be overcome, Fordham, along the American Federation for Children, invited Tamar Jacoby, president of Opportunity America, Kevin Teasley, president of the Greater Educational Opportunities (GEO) Foundation, Jon Valant, a fellow at the Brookings Institution, and Zach Verriden, executive director of HOPE Christian Schools (Wisconsin Region) to participate in a panel discussion on August twenty-second, moderated by senior vice president for research, Amber Northern.

Speaking from their unique perspectives, the four panelists covered various issues within high school choice, including getting students involved in the decision making process; aligning high school standards with higher education and career and college readiness; and making sure high schools of choice remain accountable.

Valant acknowledged concerns about letting high school students make their own decisions and stressed that safeguards are needed to ensure these decisions are being made in the long-term best interests of the student. Recognizing what he saw as necessary guardrails to implementing student choice, Valant remarked, “if kids are involved with choosing their own schools, there is a risk, and we have to be thoughtful about that. We have to think about what kind of pressures [kids] are getting in high school.”

Teasley highlighted the administrative hurdles to high school choice that he’s run into, chief of which is alignment with higher education. He also stressed that students shouldn’t be prohibited from taking courses at other high schools and explained the dual-enrollment barriers he’s encountered when helping students forge innovative course pathways. He argued that education should take the “Amazon approach,” where students and families are prioritized as consumers and schools provide access to course options: “We need to be able to provide anything [to students]; it doesn’t mean [we] will provide you everything, but we should provide you access to it.”

Verriden reiterated the difficulty of aligning high school curricula to higher education—something he’s also experienced at his network of college-preparatory schools. He highlighted the top-down model of college prep academics, commenting that due to the pressures from college and university admissions preferences, entry requirements, and expectations, “higher education dictates what you can and cannot do at the high school level—which stifles innovation within high schools.”

Many traditional, comprehensive high schools may find it difficult to partner or coordinate with technical programs and internship opportunities. Jacoby discussed how Career and Technical Education (CTE) high schools can help bridge that gap between traditional academics and hands-on training. She said that “employers are from Mars and educators are from Venus, so it’s hard to build relationships between employers and schools.” CTE-centric schools, she suggested, could help through direct cooperation with employers, apprenticeship, internship programs, and curricula designed to give students a pipeline directly to careers.

Overall, each of the panelists stressed the potential for high schools of choice to give students more pathways to careers and college. They aren’t easy to open from scratch and there are many practical hurdles in operating them, but we’d be wise to support the schools, teachers, parents, and students who are involved in these efforts.

To view the event in its entirety, visit C-SPAN.org.

Competition or cooperation? The district-charter school debate has swung back and forth between these alternative strategies since the first public charter schools opened twenty-five years ago. No group has striven harder over that period to find a workable balance than the Seattle-based Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE). Better Together: Ensuring Quality District Schools in Times of Charter Growth and Declining Enrollment is CRPE’s latest effort to bring a moderate, research-based middle-ground to the fraught charter/district relationship that is still too often defined by acrimony, blame, and zero-sum arguments.

Better Together builds on CRPE’s deep expertise in establishing and promoting “District-Charter Collaboration Compacts.” It grows out of the conversation of “more than two dozen policymakers, practitioners, researchers and advocates” that took place at CRPE’s behest in January. Can school districts and charter schools co-exist, even cooperate? Is there a “grand bargain” to be struck that could benefit both sectors while—most important—serving the best interests of students, voters, and taxpayers?

District-charter collaboration is especially challenging in communities with declining student enrollments. In Rust Belt cities like Detroit, Cleveland, St. Louis, Philadelphia, and Dayton, the district population has declined by tens or hundreds of thousands of students. Detroit, for example, watched its district enrollment drop from 292,934 in 1970 to less than 50,000 students in 2014, while St. Louis shrank from 113,484 pupils to a paltry 27,017.

Yet these same cities are also home to some of the country’s highest percentages of charter attendees—more than half in Detroit and more than 30 percent in Cleveland, St. Louis, Philadelphia, and Dayton. Not surprisingly, many supporters of traditional districts blame their enrollment woes on charter competition. Never mind that their pupil populations were shrinking before the first charter school appeared.

Facts aside, as one school finance expert observed in Better Together, “Declining enrollment may not be charters’ fault, but it is their problem.” Districts are designed to grow, not contract. Districts face bona fide legacy costs (e.g., building maintenance, debt service, transportation, unfunded pension liabilities, and inflexible teacher contracts) that make it costly and painful to right size.

For example, “last in, first out” contract provisions require that when a reduction in force is necessary, the newest and least expensive teachers must depart—along with their energy and the district’s future work force. This can lead to almost absurd outcomes, such as the time in 2008 when Dayton conferred its “Teacher of the Year” award at the same time the recipient was handed his pink slip. This hurt not only the Dayton Public Schools, but also Dayton children who lost a top-notch teacher to a far less needy suburban district.

State policies also make it hard for districts to shrink—and for charters and districts to collaborate. As one district official put it in Better Together, “These problems are often exacerbated by state funding formulas that don’t adequately reflect enrollment changes, are outdated, or at times simply are ‘bizarre.’” Further, “In many places, they often pit charter schools against district schools, either by providing different per-pupil funding formulas or ignoring stickier ‘legacy costs.’”

In some states, conservative lawmakers are simply fed up with urban districts (and their liberal voters) that spend $20,000 or more per pupil but never deliver results. On the flip side, teacher union opposition to charters make it impossible in some communities for charters and districts to even hold a civil conversation, much less work together.

While Better Together focuses on the challenges facing urban districts and charters, the experiences and positions that it surfaces apply to rural communities, too. In Gooding, Idaho, population less than 1,400, a charter school opened in 2008 and 10 percent of the district’s pupils shifted into it during a single summer. This precipitated brutal fights in Gooding and in the Boise statehouse, with one side claiming that the charter would bleed the district of essential resources and the other saying that children needed education options and opportunities that the district couldn’t (or wouldn’t) provide. Rural districts and their charters need to figure out how to work better together as much as do those in declining metropolises.

Better Together offers some “first steps towards solutions” that are relevant to urban and rural communities alike. These include:

- Finding ways to help districts reduce legacy costs;

- Organizing new forms of tight-loose school governance where districts, mayors, or state-sanctioned entities provide quality control for all schools in a city, regardless of who manages them—and enabling school operators to run schools with minimal top-down mandates;

- Joint advocacy where district officials and charter leaders work together for improved state policies such as weighted student funding and teacher pension reform;

- Better research on the financial impact of charter schools and how districts in fact manage enrollment declines; and

- Drawing lessons from other sectors (e.g., healthcare and energy) that have faced profound structural changes in recent years, and applying what works to school improvement efforts.

Some of the proposed solutions in Better Together are already being field-tested. For example, the 2012 Cleveland Plan for Transforming Schools (based in large part on CRPE research) created a Transformation Alliance that seeks to ensure that all new charter schools in the city are high quality. It scrapped rules making seniority the deciding factor in teacher layoffs, and it authorized the district to share local levy dollars with high-performing charters.

There’s much debate about how well this is working in Cleveland—and it’s not going to be easy anywhere. Better Together is honest about the challenges that such efforts face in places with shrinking populations. But it also makes a strong case for how communities and children benefit when school districts and charters work together.

SOURCE: Better Together: Ensuring Quality District Schools in Times of Charter Growth and Declining Enrollment, Center on Reinventing Public Education (September 2017).

Terry Ryan is the CEO of Bluum, an Idaho-based school reform organization. For ten years he led Fordham’s education reform efforts in Ohio.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

We’ve known for a while—thanks to the National Assessment and other measures—that American primary-secondary students aren’t learning a heckuva lot of civics, never mind that social studies is taught everywhere and taking high school civics is a widespread graduation requirement. Indeed, the Education Commission of the States reports that:

- “Every state requires students to complete coursework in civics or social studies in order to graduate….

- Thirty-seven states require students to demonstrate proficiency through assessment in civics or social studies. [and]

- Seventeen states include civic learning in their accountability frameworks.”

That it isn’t working very well was obvious when, for example, NAEP assessed civics in 2006 and found that fewer than a quarter of high school seniors could supply a satisfactory answer to a question about the means by which citizens can change laws. Or when the Annenberg Public Policy Center surveyed American adults in 2014 and found that only 36 percent could name the three branches of the U.S. government.

That it isn’t working very well on a long-term basis is painfully evident from the recent behavior, voting patterns, and discourse of millions of American adults, including some at the highest levels of government.

Fortunately, there’s continuing awareness that this is an unsolved problem, including personal attention from such eminences as Sandra Day O’Connor and Colin Powell—and a “summit” today that’s devoted to catalyzing improvements in it.

What’s brought this failure into sharpest relief in recent days, however, was release of a seriously alarming survey by the Brookings Institution’s John Villasenor. He polled college students last month to gauge their understanding of the First Amendment’s free-speech clause.

(In case you’ve forgotten, the exact wording says “Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech…or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” And in case you’ve forgotten another key bit, in 1925 the Supreme Court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment extended this protection to apply to state as well as federal actions.”)

Nothing is more basic to civic education than the First Amendment, and nothing is more fundamental to a free society than freedom of speech. We pretty much take for granted that this is a keystone of anything called civic education. Moreover, an occasional criticism of civics curricula is that they overemphasize citizens’ rights at the expense of their responsibilities.

Yet check out Mr. Villasenor’s survey findings—and keep in mind as you do that those he is surveying are current college students, which means (a) they are recent products of K–12 civics education and (b) they are among the more successful products of our K–12 education system.

Here’s some of what he found:

- “Does the First Amendment protect ‘hate speech’?”

- Just 39 percent said yes.

- A “public university invites a very controversial speaker to an on-campus event,” a person “known for making offensive and hurtful statements,” and “a student group opposed to the speaker disrupts the speech by loudly and repeatedly shouting so that the audience cannot hear the speaker...Do you agree or disagree that the student group’s actions are acceptable?”

- 51 percent said yes (including 62 percent of those who identify as Democrats).

Words fail me. “Appalling,” “unacceptable,” “outrageous”, “inexcusable.” None of them does justice to the implications of these findings. More than half of current U.S. college students think it’s OK to shout down a speaker who says offensive things. Not even two out of five understand that the First Amendment protects the kinds of speech that you don’t like hearing.

The survey goes on to show that many also think it’s OK to use violence to suppress such speech from being uttered—or heard.

No wonder the Wall Street Journal editorialized that “Madison Weeps.”

It’s important, obviously, for the colleges themselves to clean up their acts, though it won’t be easy given the dispositions and behavior of many faculty members and the wimpishness of campus leaders.

But what does this say about civics education before they get to college—and go out into adult life? It says to me we are looking at a total failure. Indeed, it says to me that Mr. Villasenor’s survey tells us once again that we remain a nation at risk.

No, it’s not entirely the schools’ job to inculcate both civics knowledge and civic values (and civil behavior) into young people. Parents, community groups, churches, scouts and coaches share this responsibility. But fifty states think they’re teaching civics.

How well are they doing it? I’m reminded of an old but telling query by Sy Fliegel (early hero of school choice in New York): “Define the word ‘taught’ in the following sentence: ‘I taught my son to swim but every time he gets into the pool he sinks to the bottom.’”

This is serious, folks.