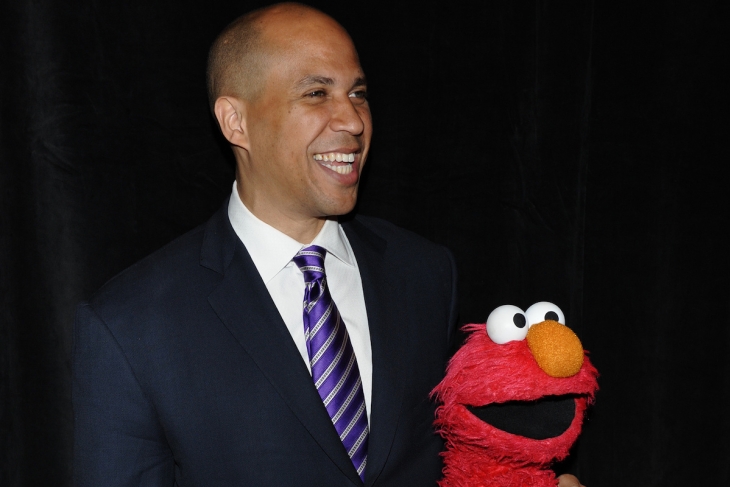

With 371 declared Democratic candidates for president, and many of them doubling down on the teacher-union-defined status quo in education, reformers are all in for New Jersey Senator Cory Booker.

Both as mayor of Newark and as the state’s junior senator, Booker’s embrace of charter schools and tech partnerships, as well as his chumminess with Trump administration Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, have made him the darling of ed policy wonks. “I could shoot my friend T-Bone in the middle of Broad Street in Newark and I wouldn’t lose any votes from the education reformers,” Booker recently told a rally.

Booker’s missteps in the Kavanaugh hearings, dad jokes about dating “hot coffee” on twitter, and many subsequent public gaffes haven’t dented his support in the reform crowd. A recent analysis of reformers’ campaign donations by Rick Hess and Jay Greene showed that rank-and-file workers at education policy organizations donated overwhelmingly to Democrats in the Trump era. But they neglected to point out that reformers’ giving would have been far more equitable between the political parties if not for donations to Spartacus himself, as an updated analysis by the Gladfly demonstrates:

And indeed, on Monday, April 1, Democrats for Education Reform will be hosting a panel on the successes of Newark’s Facebook-funded reforms, with a vodka margarita happy hour to follow.