Public-school groups’ latest stratagem: Tie Ohio’s voucher program in red tape

It’s no secret that the public-school establishment pulls out all the stops to prevent families from exercising educational choice, including private school options.

It’s no secret that the public-school establishment pulls out all the stops to prevent families from exercising educational choice, including private school options.

It’s no secret that the public-school establishment pulls out all the stops to prevent families from exercising educational choice, including private school options. More than one hundred school districts, for instance, have lined up in support of a lawsuit that aims to kill in one fell swoop EdChoice, a program that provides state-funded scholarships for about 125,000 Ohio students to attend private schools.

Their latest strategy: tying up private schools in red tape in an effort to weaken them via a thousand regulatory cuts. Introduced earlier this spring, the vehicle for this broadside is House Bill 407. The legislation would heap a number of new and intrusive reporting requirements on private schools regarding their building capacities, admissions standards, expenditures, the income brackets that students’ parents are in, and the schools that students attended in the prior year. It would also reinstate a former requirement that private schools administer state assessments to scholarship students instead of permitting the use of alternative exams, and calls for some type of private school report card. While there is more merit to those outcome-driven proposals, they would discourage school participation in EdChoice and are being pushed, ironically, by education groups that have long resisted these types of accountability measures for their own schools.

Who exactly is advocating hardest for the bill? In committee testimony, the district school boards, superintendents, treasurers associations, and both teachers unions—the entire public-school establishment—voiced full support for the legislation. These longstanding opponents of private-school choice all plugged some variation of the argument that more regulation is needed to “level the playing field” and to help parents access more information about private schools.

Let’s be clear from the start: This effort isn’t about fair competition or parental empowerment. Rather, it’s blatant, anti-competitive behavior cloaked in “accountability.” What the public-school groups are doing is no different than corporations lobbying for policies and regulations that prevent the competition from gaining a foothold. None of these groups have ever argued to increase private school funding to bring their amounts in line with public schools (that would bring some “fairness” to the table). It’s also hard to say that parental rights is their focus when they file lawsuits aimed at robbing families of school choice and constantly ridicule programs that provide more options. It’s also tough to take the testing requirement seriously when pushed by groups that regularly attack state tests. And report cards? Just a few years ago, these very groups (unsuccessfully) lobbied the legislature for an opaque public school report card that would have been useless to parents.

But since private school accountability is at issue—and because they are often criticized by their opponents as being “unaccountable”—it’s worth reviewing yet again the ways in which private schools are accountable.

First and foremost, private schools are directly accountable to the families they serve. When parents are dissatisfied, they can head for the exits. One might say the same is true for public schools. The difference is that private schools no longer receive funding when a student leaves—they lose the state scholarship amount, if applicable, plus any tuition along with the student. If they suffer significant enrollment and financial losses, they have no choice but to close their doors. This form of accountability—financial consequences directly tied to enrollment losses—is a key incentive for private schools to provide a quality education.

Traditional districts, on the other hand, are shielded from the financial pain of enrollment declines through the state’s longstanding use of funding guarantees and local property tax revenues that are not tied to enrollment. Moreover, because a school district must cover every corner of the state, districts have built-in protections from permanent closure. The weaker “market discipline” in the district sector is one reason why school reformers have typically pursued results-driven accountability measures that incentivize districts to pay attention to the needs of students.

Remember also that Ohio’s private schools are already held to many of the same standards as traditional public schools. They must be formally “chartered”—a form of accreditation—by the state,[1] and through that process, they must adhere to the state operating standards that apply to public schools, as well. Moreover, a school’s charter can be revoked for noncompliance with state laws and regulations, and they must follow racial nondiscrimination policies. This regulatory structure makes sense, balancing school autonomy with necessary guardrails, and has served Ohio well for decades.

As for academic outcomes, Ohio has long required scholarship students in particular grades to take a standardized exam. As noted earlier, students were formerly required to take the state test, and their proficiency rates were reported in the aggregate for each school. In 2019, the General Assembly changed the law to allow private schools to administer a state-approved alternative exam that might align more closely with a school’s curriculum. Proficiency rates on these tests are still reported and, last year, state lawmakers added an important new requirement: Scholarship students’ growth results will now be calculated and reported, as well. This additional data point (which entails no new testing burdens) will soon provide a clearer picture of the yearly academic progress of students attending private schools. Lawmakers would be smart to see how the state’s new growth measure helps inform the public before turning back the clock on assessment or instituting a report card system.

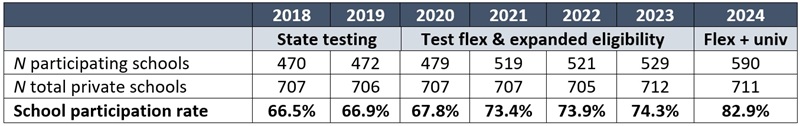

It’s important to recognize that adding further regulations on top of the existing framework would only discourage private schools from participating in EdChoice—indeed, very conceivably what the public-school groups hope will happen. In Louisiana—a state with onerous regulations—only one-third of private schools decided to participate in its scholarship program, thus limiting the choices of families and likely to schools of lessor quality. Fortunately, as the table below indicates, Ohio has done better, as two in three private schools participated in EdChoice as of 2018–19. With expanded eligibility and testing flexibility, four in five accepted EdChoice scholarships this past year. Increasing state regulations, as HB 407 proposes, could wipe out this progress in private-school participation.

Table 1: Private school participation rates in EdChoice (income-based or low-performing schools)

Back in 2016, along with my colleague Chad Aldis, I wrote: “Policymakers should tread lightly when adding to schools’ regulatory burdens. After all, freedom from regulation is precisely what makes private schools different and—for many—worth attending in the first place.” I stand by that statement. Rather than pursuing ill-advised attempts to conform private schools into the image of public schools, the state should allow for distinctive schools that meet the varying needs of Ohio families.

[1] Private schools eligible to participate in EdChoice are technically known as “chartered, nonpublic schools.” These schools are not the same as public charter schools.

Last year, state officials published some troubling data related to Ohio’s teacher workforce. They revealed that fewer young people are entering the profession, teacher attrition rates have risen, and worrying shortages exist in specific grades and subject areas.

To their credit, state leaders correctly interpreted these data as a warning sign and took action. The state budget included provisions to make teacher licensure more flexible and expand the pool of substitute teachers. Ohio now also has a Grow Your Own Teacher Scholarship Program and a Teacher Apprenticeship Program.

These were positive steps forward. But they focus primarily on bringing new teachers into the profession. That’s only one part of the equation. Let’s reexamine two previously pitched ideas that could help retain the teachers we already have.

1. Allow districts to pay teachers more flexibly by eliminating mandatory salary schedules based on seniority and credits earned.

Low salaries are often cited as a reason why students steer clear of the teaching profession and why some teachers choose to leave the classroom. Given the importance of teachers to student success, state and local leaders should be looking for ways to boost teacher pay regardless of the retention implications. But absent a sudden (and permanent) influx of cash, it will be difficult to raise salaries across the board. That’s where flexible salary schedules come in.

Under current law, districts must adopt teacher salary schedules based on years of service and training. These systems have the benefit of simplicity, as teachers can predict with some certainty when and how they will receive a raise. But there are also drawbacks. Mandatory schedules typically prescribe low starting salaries to early career teachers, which can drive young talent—especially teachers with considerable student loan debt—out of the profession. Rigid schedules thwart districts’ ability to reward high performers based on effectiveness or increased responsibility, which could prod our best and brightest into other professions. Salary schedules also make it difficult to bolster specific high-need areas, like special education. The number of students with special needs is rising, and special education is a potential shortage area in Ohio. Offering special education teachers additional pay could help with recruitment and retention, but current law and collective bargaining agreements make that difficult.

Repealing salary-schedule requirements would empower districts to determine how best to pay their instructional teams. State leaders should not make flexible pay mandatory. Schools should be able to stick with traditional rigid schedules if they prefer. But making room for greater flexibility would allow leaders to strategically allocate funds in a way that better serves students and helps recruit and retain staff.

2. Create a refundable tax credit for teachers working in high-poverty schools.

High-poverty schools need effective teachers. But issues such as lower salaries, inadequate support from administration, school culture and student discipline issues, and high turnover rates hinder schools’ ability to recruit and retain talent. Addressing all these problems would require a host of structural reforms, but the state could alleviate concerns about low salaries by creating a tax credit for teachers who work in high-poverty schools. Such a program would allow state leaders to put more money directly into teachers’ pockets without getting tangled up in salary negotiations with local unions and school boards. It would also provide a modest financial incentive for teachers to choose to work in high-need schools.

***

To strengthen Ohio’s teacher workforce, state leaders need to invest in a variety of initiatives. There are plenty of ideas worth considering, but making sure that teachers have more money in their pockets should be at the top of the list.

Over the last few years, Ohio leaders have focused on improving education-to-workforce pathways through a variety of initiatives and funding. Thus far, there’s been plenty of commendable progress. But significant challenges remain.

For ideas on how to overcome these challenges, state leaders should consider the State Opportunity Index that was recently released by the Strada Education Foundation, a national organization that works to strengthen the link between post-secondary education and opportunity. The index was designed to provide states with a quantifiable set of indicators they can use to assess how well they’re leveraging post-high school education—not just degrees, but certificates and other credentials, too. It establishes a baseline for states in five priority areas: clear outcomes, quality coaching, affordability, work-based learning, and employer alignment. States’ progress within each of these areas is categorized as leading, advanced, developing, or foundational.

How did Ohio fare on the index’s ratings? Not well. The state earned its highest rating—advanced—in the clear outcomes category. The work-based learning and employer alignment categories were rated as developing. Meanwhile, the quality coaching and affordability measures ranked the worst, with bottom-of-the barrel ratings of foundational.

To be clear, most of the data used by the index focus on college graduates. But there are useful insights for Ohio’s K–12 sector. In fact, there are some especially useful data points in the clear outcomes area, where Strada identified ten key education-to-employment data system elements, evaluated states’ progress on each element based on survey responses and an extensive review of publicly available information, and then assigned states a rating for each element, as well as an overall rating. In terms of individual ratings for each element, Ohio did particularly well—earning the highest available score of leading—in three areas: partnerships for outcomes data outside the state, interactive resources, and researcher access. But the state also earned low- or bottom-level ratings on three other elements. Here’s a look at each, and what Ohio can do to improve.

1. Integrating high school completion and employment data

This element evaluates how well states integrate and deliver information on learners’ earnings and employment after high school completion, as well as over time. The majority of states (twenty-nine) fell into the bottom two rating categories. Ohio was one of six to earn a rating of developing, indicating that the state is currently in the process of implementing information integration efforts related to earnings and employment after high school. The index notes that these implementation efforts are being done through the Coleridge Initiative, a nonprofit that works with government entities to ensure that data are used effectively in public decision-making. The Ohio Department of Higher Education and the Ohio Education Research Center are working together to expand the Multi-State Post-secondary Dashboard (which is powered by the Kentucky Center for Statistics) to track high school and non-degree employment outcomes in Ohio.

Although Ohio earned a developing rating in this area, Ohioans have cause for optimism. State leaders and agencies are already working on tracking these data. Going forward, leaders should focus on accomplishing two goals. First, these outcomes data should be published and easily accessible to the public, as well as disaggregated by demographics to ensure transparency. Second, state and local leaders should consistently use these data to drive policy decisions.

2. Open data files

This element determines whether states provide comprehensive and timely open data files containing “anonymized education-to-opportunity statistics” that anyone can access, download, and use. The index notes that these offerings should include downloadable databases, clear explanations of the resources, and data dictionaries. Public databases that contain only aggregate information—meaning individual learners can’t be identified from the data—would allow researchers, policy organizations, and members of the public to easily access information for analysis and reporting.

Twenty-one states earned a foundational rating on this element, either because their open data files contain only enrollment and completion metrics and no employment outcomes, or because they have no open data that Strada could identify. Ohio was one of the twenty-one, with the index noting that “no evidence was identified.” To improve, Ohio should look to the seven states that earned the index’s top rating. Colorado, for example, offers customizable open data files that contain a variety of disaggregated education-to-opportunity statistics. Kentucky, meanwhile, offers open data files containing disaggregated education-to-employment outcomes by program for public four-year universities, community colleges, non-degree credentials, and high school. It also provides files on apprenticeships, adult education, and career and technical education.

3. Dedicated insights capacity

This element evaluates whether states have designated a unit with responsibility and dedicated full-time capacity for generating education-to-employment insights. To earn the top rating, states must have a unit that meets four criteria:

Only seven states—Arkansas, Colorado, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, Nebraska, and Virginia—met all four of these criteria. The index found that Ohio, which was assigned the lowest rating of foundational, had “no evidence” of demonstrating this element.

Going forward, Ohio leaders should consider what’s been established in the seven top-rated states. For example, the Virginia Office Of Education Economics is a politically independent office that works with a wide variety of state agencies and partners to “collaboratively offer resources and expertise related to education and labor market alignment.” Mississippi, on the other hand, has the National Strategic Planning & Analysis Research Center at Mississippi State University, which provides high-quality research and analysis in addition to maintaining the statewide longitudinal data system.

***

When it comes to education-to-career pathways, Ohio leaders would be wise to remember the adage that Rome wasn’t built in a day. The Buckeye State has made considerable progress over the last few years. But there’s still plenty of work to be done. Some areas, like integrating high school completion and employment data, only need to be shepherded across the finish line. Others—like providing open data files and designated insights capacity—will require considerably more effort and investment. If state and local leaders are committed to continuing Ohio’s growth, Strada’s State Opportunity Index is worth a close look.

What are the best ways to deploy finite resources for the betterment of young children? What inputs provide the most beneficial outcomes later in life? These are big, important questions whose answers matter to individuals, families, and society. A new report from Urban Institute’s Income and Benefits Policy Center aims to provide the answers.

Authors Kevin Werner, Gregory Acs, and Kristin Blagg build on a large body of previous research showing the well-established link between childhood and adult outcomes. They add to the literature by constructing a model that simulates changes in several variables at different points in children’s lives and projecting their outcomes as adults. Data come from the Social Genome Model (SGM), a microsimulation model of the life cycle that tracks the academic, social, and economic experiences of individuals from birth through middle age in order to identify the most important paths to upward mobility. They translate SGM data to match real world data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey-Kindergarten Cohort (ECLS-K) for childhood outcomes at ages five, eight, and eleven, and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 Cohort (NLSY97) for adult outcome data.

Their model focuses on a single adult outcome: earnings at age thirty. While this is mainly because age thirty is currently the extent of the SGM data, they also consider earnings a useful proxy measure for other aspects of adult life, “given the strong relationship between higher income and other indicators of well-being, such as physical and mental health.” Additionally, research has shown that earnings at age thirty are predictive of lifetime earnings.

They look at sixteen different factors across four different stages of childhood: birth, preschool, early elementary school, and middle childhood. The model contains variables from five different domains for each life stage, comprising cognitive and academic development, emotional and psychological development, physical health and safety, mental health, and social behaviors. The changes their model introduce to childhood circumstances are all improvements, and all important. Examples include increasing birth weight to safer levels, boosting math and reading test scores by 0.5 standard deviations, and improving health indices by 0.5 standard deviations. Changes are introduced at various points in childhood to determine their adulthood impact.

Findings indicate that improving children’s math scores outshines all other factors and increases adult earnings the most. Improving preschool (age five) math scores by 0.5 of a standard deviation yields an impressive 2.5 percent increase in earnings at age thirty; doing so in middle childhood (age eleven) raises earnings by 3.5 percent, which corresponds to about $1,200 per year (in 2018 dollars) in additional earnings for the average adult. Roughly similar impacts are seen in children of all races and ethnicities across life stages, with Hispanic children consistently seeing the largest gains. Girls tend to see a higher earnings boost than boys. By comparison, improvements in childhood health indices result in small but steady earnings increases of 0.6 to 0.7 percent in adulthood, with larger gains for Black and Hispanic children as compared to their White peers. Improvements in reading test scores (again, 0.5 of a standard deviation) give a nearly 1 percent bump to adult earnings when they happen at age five, but decline by half when they occur at age eleven.

The authors do not discuss potential mechanisms at work, given the exploratory nature of their analysis, and the findings as discussed are simplified for the same reason. “Increasing math achievement by 0.5 standard deviations” is far more easily done on a computer than accomplished in practice, but real-world research has shown that there are many ways both inside and outside the classroom to help students improve their math performance. Thus two important points emerge from this exercise. First is that policymakers can and should direct resources toward interventions and supports that are proven to provide the largest boost for the families they serve. This analysis suggests that math success in childhood is critical to adult—and lifetime—success. Second, we have multiple ways to accomplish in the real world what computer scientists can do with the click of a mouse. Urgent dedication from all stakeholders to the goal of improving math scores for students is required, with the broadest support and resources possible, as an investment in children’s (and families’ and society’s) futures.

SOURCE: Kevin Werner, Gregory Acs, and Kristin Blagg, “Comparing the Long-Term Impacts of Different Child Well-Being Improvements,” Urban Institute (March 2024).

By Aaron Churchill

Over the past two decades, researchers have spent countless hours studying the impacts of public charter schools—independently-run, tuition-free schools of choice that serve some 3.7 million U.S. students today. Just prior to the pandemic, studies from Ohio and nationally indicated that charters on average delivered superior academic outcomes compared to traditional districts. And the very finest charters in Ohio and around the nation were driving learning gains that gave disadvantaged students the edge needed to succeed in college and career.

The pandemic scrambled most everything about K–12 education. But did it upend what we know about charter school performance? The present study, conducted by Fordham’s Senior Research Fellow Dr. Stéphane Lavertu, examines the post-pandemic performance of Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charter schools, which enrolled 81,000 students—mostly from urban communities—during the 2022–23 school year.

Dr. Lavertu’s analysis of state value-added data indicates that the charter school advantage has persisted in the wake of the pandemic. In 2022–23, the average brick-and-mortar charter school delivered the annual equivalent of roughly 13 extra days of learning in English language arts and 9 extra days in math. While the size of the ELA advantage (though not math) has diminished since the pandemic, the average Ohio charter school still outperforms nearby district schools.

There, of course, remains tremendous work ahead to help all students—district and charter alike—to achieve at high levels after pandemic-related disruptions. But one thing’s for sure: Supporting—and investing in—high-quality public charter schools remains a strong, evidence-based approach that Ohio should continue to embrace.

Aaron Churchill

Ohio Research Director

Thomas B. Fordham Institute

Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charter schools were going strong prior to the pandemic. Rigorous studies demonstrated that student test scores in English language arts (ELA) and mathematics improved significantly when students attended charter schools instead of nearby district schools. Disciplinary incidents and absenteeism also declined significantly. Such results were not mere correlations. These studies used research designs that plausibly unearthed charter schools’ causal impacts on student outcomes. Thus, just prior to the pandemic in the spring of 2020, there was little doubt that Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charter schools were, on average, high-quality alternatives to district schools, particularly for lower-income families residing in our state’s large urban districts.

The pandemic hit the typical school hard, but it hit charters even harder. Charter operators noted that tight labor markets and substantially lower funding (about $5,000 less per pupil than nearby district schools at the time) made it difficult to recruit and retain teachers during these turbulent years. Additionally, the economically disadvantaged students charters primarily serve were disproportionately derailed by the pandemic, in part because of school closures and transportation issues. Research shows that urban district and charter schools serving lower-income students experienced much steeper declines in test scores than the average Ohio public school.

With the pandemic in the rearview mirror, do Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charter schools remain a quality educational option? To answer that question, we need to determine whether the average Ohio charter school student is still learning more during the school year than they would in a nearby district school. Fortunately, Ohio’s publicly available school “growth” measures can help us make such a determination.[1]

This research brief examines how the average achievement growth of Ohio’s charter students compares to that of the average district student. The results reveal that, in terms of student achievement growth, Ohio’s charter schools remain a better educational option for the average charter student. During the 2022–23 school year, the average charter student experienced achievement gains in ELA and math that were approximately 0.02 of a standard deviation greater than students in nearby district schools. That is comparable to the average achievement impact of 0.03 standard deviations associated with increasing school budgets by $1,000 per pupil for four years; but, in the case of Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charters, those gains are realized every one or two years and at no additional cost. Indeed, during the years of this study, the achievement gains came with a significantly lower cost compared to district schools.[2] The estimated charter advantage is roughly equivalent to charter students participating in an additional 13 days of learning in ELA and an additional 9 days of learning in math every school year.

It is important to keep in mind that charter school performance is not what it was in 2019, and the average charter school student experienced significant learning loss during the pandemic. However, the results of this analysis imply that the pandemic-induced achievement gap between higher- and lower- income students would have been even worse without charter schools.

To estimate the causal impact of charter schools, we need to compare their pupils’ learning to the learning of identical students who did not attend charter schools. In other words, we need to make sure that the only relevant difference between charter and district students is the school they attended. It seems like an impossible task, as students who attend charter schools can be quite different from students who remain in district schools. Statewide, charter students are disproportionately economically disadvantaged, and a basic comparison of their test scores to the statewide average doesn’t tell us much about the actual effectiveness of their schools. Comparing students attending charter and non-charter schools in the same district (as opposed to statewide) helps in making apples-to-apples comparisons of their outcomes, as these students are more alike. But significant problems remain. For example, parents who are aware of charter schools and navigate the process of enrolling their children are likely quite different than those who do not. They likely confer knowledge, skills, and other behavioral attributes to their children that lead to higher student achievement, which one might falsely attribute to charter schools when conducting a simple comparison of charter and non-charter students within a district.

Fortunately, research has shown that focusing on achievement gains—what some refer to as student “value added” or “academic growth”—can yield estimates of school effectiveness that are minimally biased.[3] Value-added estimates hold constant a student’s achievement level as of a prior school year, effectively controlling for all differences between students that contributed to different educational outcomes up to that point in their lives. For example, an annual value-added estimate for grade 4 holds constant students’ grade 3 achievement level, which captures what happened in their life that led to their grade 3 achievement, from how well-nourished they were while in the womb, to how much stress they experienced growing up, to the quality of the educational experiences they had through third grade. Research indicates that so long as one focuses on students residing in a similar geographic area, comparing value-added achievement gains between charter and district students should get us close to the impact estimates we would get from an experiment that randomly assigned students to charter and traditional public schools (the “gold standard” for estimating causal impacts).[4]

Ohio’s school-level “growth” measure captures the average test-score gains of schools’ students relative to the average Ohio student. Consequently, one can compare the effectiveness of charter and traditional public schools operating in the same district by comparing these school-level estimates, which are publicly available on the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce (ODEW) website. The primary drawback is that these estimates are scaled differently than those in the academic literature, which makes it difficult to benchmark effect sizes. The appendix describes how I adjusted “gain” estimates (from 2018–19) and “growth” estimates (from 2021–22 and 2022–23) to get the proper scale and render pre- and post-pandemic estimates comparable.[5] It also describes how I used these rescaled estimates to create ELA, math, and science “composite” value-added scores that are comparable to those on Ohio’s school report cards.

The analysis below compares student achievement gains between brick-and-mortar charter and traditional public schools operating in the same district.[6] Note that these estimates are weighted by the number of tested students to account for measurement error. That enables us to speak in terms of the average charter student (as opposed to the average charter school) and approximates the estimates one would get using a student-level dataset. The appendix provides a full accounting of the methods and results that underlie the figures.

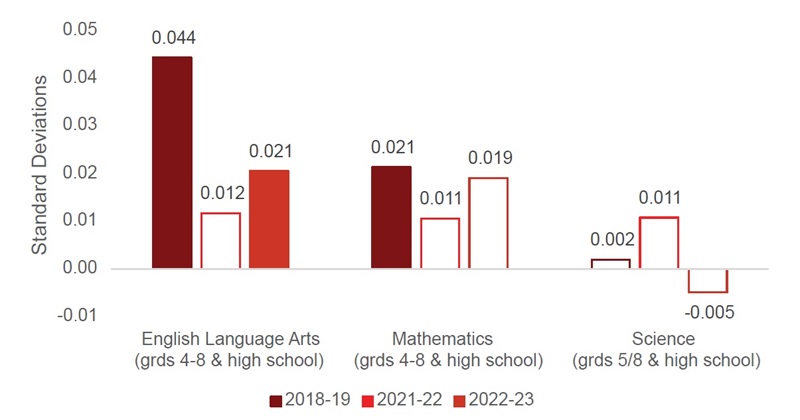

Takeaway 1: Brick-and-mortar charter schools continue to yield greater achievement gains than nearby district schools, but their advantage in English language arts is smaller than in 2018–19.

Figure 1 (below) reports the estimated difference in achievement growth between students in charter schools and students attending traditional public schools in the same district. Specifically, it presents “composite” estimates for English language arts (combining results from Ohio state tests in grades 4–8 and the high school ELA 1 and ELA 2 exams), mathematics (combining state tests in grades 4–8 and high school Algebra I, geometry, Integrated Mathematics I, and Integrated Mathematics II), and science (combining state tests in grades 5 and 8 and the high school biology exam).[7] The figure disaggregates estimated effects by subject so that pre- and post- pandemic estimates are comparable. This disaggregation compromises statistical precision and, thus, yields some estimates that do not quite reach conventional level of significance. But the comparisons are nonetheless informative.

The figure indicates that, compared to their counterparts in district schools, students attending charter schools in 2022–23 had test score gains that were 0.021 of a standard deviation greater on ELA exams. Thus, after a notable dip in 2021–22, a charter advantage reemerged in 2022–23. However, that advantage is less than half the size it was in 2018-19—a statistically significant drop. The results also suggest that after an initial dip in 2021–22, charter schools regained their advantage in math of approximately 0.02 standard deviations in 2022–23.[8] The math estimate narrowly fails to attain conventional levels of statistical significance (hence the empty bar) but the results nonetheless suggest that the charter advantage in math is back to pre-pandemic levels.[9] Finally, charter schools performed comparably to nearby district schools on science exams, both before and after the pandemic.

To validate these results, I re-estimated the models using the composite value-added measures publicly available on Ohio’s school report cards (labeled “effect sizes” on the report cards). These additional analyses confirm the value-added estimates in Figure 1 and reveal that pooling all tested subjects across both post-pandemic years (2021–22 and 2022–23) yields a statistically significant charter school advantage of approximately 0.017 standard deviations.[10]

Figure 1. Differences in achievement gains between charter and district students

Translating these estimated charter school effects into the more intuitive “days’ worth of learning” metric is not straightforward, in part because of the inclusion of high school exams that are not administered in consecutive years. Nevertheless, with this caveat in mind, the estimates for 2022–23 are the equivalent of charter students participating in an additional 13 days of learning in ELA (as compared to 28 days as of 2018–19) and 9 additional days of learning in math (as compared to 10 days as of 2018–19).[11] These are rough approximations, but they provide some intuition about the magnitude of the post-pandemic charter school achievement advantage in ELA and math.

Takeaway 2: Students in brick-and-mortar charter schools experienced large gains on high school exams (relative to students in nearby district schools), which helped sustain the charter advantage since the pandemic.

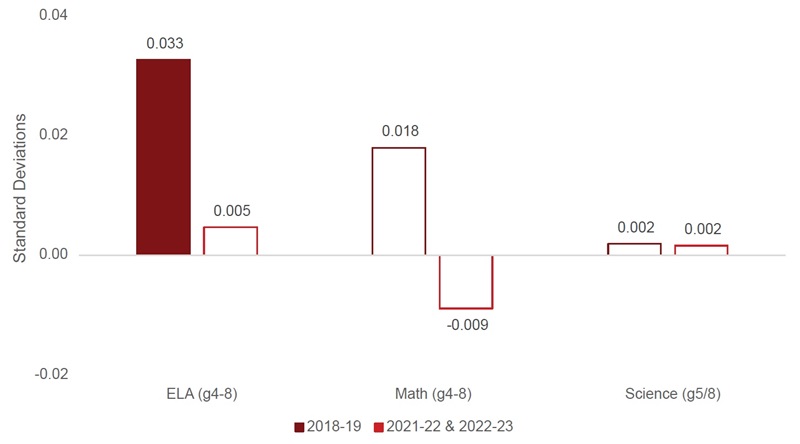

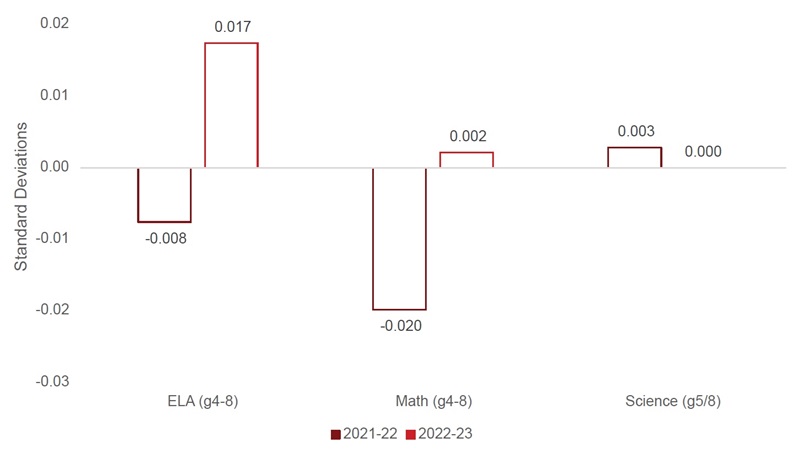

The analysis below disaggregates the estimates in Figure 1 by grade band and subject. Figure 2 (below) focuses on student achievement in grades 4–8 and, to maximize statistical power, pools the value-added estimates from the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years.[12] These estimates capture annual learning gains. For example, during the 2018–19 school year, the average charter school student gained an extra 0.033 of a standard deviation per year in ELA compared to their peers in district schools. The results in Figure 2 indicate that charter schools’ pre-pandemic advantage for students in grades 4–8 was wiped out in 2021–22 and 2021–23. In other words, considering all post-pandemic years together, charter school students in grades 4–8 learned no more (but no less) than their counterparts in district schools.

Figure 2. Differences in achievement gains between charter and district students (grades 4–8)

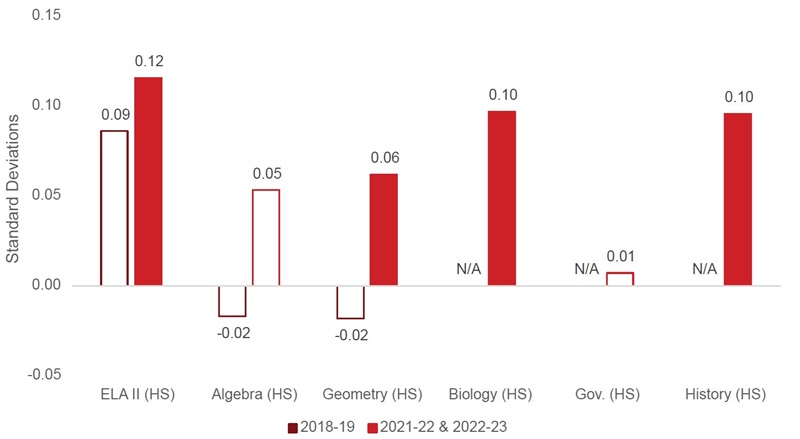

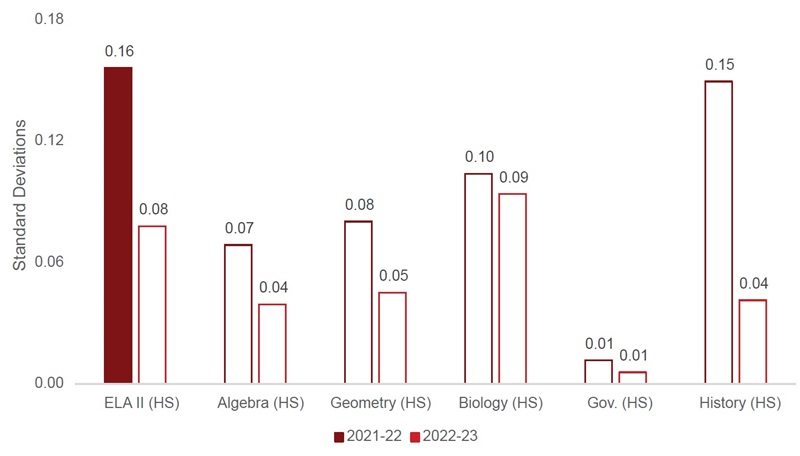

Figure 3 (below) presents the results for tests that students typically take in high school, including some for which we have no value-added estimates for the 2018–19 school year (biology, government, and history).[13] It indicates that the charter school advantage for the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years (indicated in Figure 1) is driven predominantly by student achievement on high school exams. Interpreting the effect sizes for high school exams is less straightforward than interpreting the annual achievement gains presented in Figure 2, as the value-added estimates for high school often capture multiple years of learning as opposed to annual achievement gains.[14] The difficulties with comparing the estimates in Figure 2 and Figure 3 do not detract from the primary take-home message, however: The 2018–19 charter advantage in grades 4–8 shifted to an advantage in high school during the 2021–22 and 2022– 23 school years. This shift underlies the ostensibly stable charter school impact estimates for mathematics that appear in Figure 1.

Figure 3. Differences in achievement gains between charter and district students (high school)

It is important to reiterate that both charter and district students lost significant ground during the pandemic, and that these analyses compare achievement gains between students in charter and district schools. Thus, the large “increases” in charter school value-added on high school exams are due in part to charter students losing less ground than their counterparts in district schools, as opposed to an absolute improvement in the achievement of charter school students. Similarly, the estimates for grades 4–8 indicate that the annual achievement gains of charter students became identical to those of district students, which is a “decline” in the sense that charters lost the (substantial) advantage in achievement gains their students enjoyed as of 2018–19.

Takeaway 3: Brick-and-mortar charter schools’ achievement advantage in grades 4–8 appears to be on the rebound.

The analysis above pools value-added estimates from the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years to enhance statistical power. But were there changes in the impact of charters between 2021–22 and 2022–23? Although Ohio’s value-added estimates are generally too imprecise to estimate impacts annually for particular grade bands and subjects, examining the differences in effects between the two post-pandemic school years suggests some interesting patterns. Figure 4 indicates that, from 2021–22 to 2022–23, charter schools’ value-added (relative to district schools) increased by 0.025 of a standard deviation on ELA exams (from -0.008 to 0.017) and 0.022 of a standard deviation on math exams (from -0.020 to 0.002) in grades 4–8. These results contrast with a relative decline from the exceptionally high 2021–22 value-added for high school grades that Figure 5 presents.[15]

It is worth emphasizing that one should not make too much of the estimates in Figures 4 and 5 (below), as they are too imprecise to draw conclusions with statistical confidence (hence the empty bars). For example, the estimate of 0.017 for ELA in grades 4–8 narrowly fails to attain statistical significance; we cannot rule out a substantively significant effect.[16] A charter student with an extra 0.017 of a standard deviation in annual ELA achievement in grades 4–8 would have accumulated an achievement advantage of 0.085 of a standard deviation (5 years x 0.017) by the end of eighth grade. That equates to approximately an additional 49 days’ worth of learning after five years. So, these by-year analyses do not enable us to rule out substantively important charter school effects. Figures 4 and 5 illustrate trends, as opposed to making a conclusive statement about the true impact of charter schools in 2022–23.

Figure 4. Differences in achievement gains between charter and district students (grades 4–8)

Figure 5. Differences in achievement gains between charter and district students (high school)

The analysis indicates that the average student in Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charter schools continues to learn more than they would in nearby district schools. Indeed, the achievement gains that charters generate in English language arts and mathematics would likely be expensive to realize if, instead of charter schools, we sought to achieve them by increasing funding of district schools. Make no mistake: Students in charter and urban district schools experienced larger achievement declines during the pandemic than students in the average Ohio public school. Charter school students indeed fell behind during this period. However, the results of this analysis imply that the pandemic-induced achievement gap between higher- and lower-income students would have been even worse in the absence of charter schools.

Setting aside pandemic-related learning loss, the results above also serve as a reminder that there is room for improvement in Ohio’s charter sector. Ohio’s charter schools do not provide quite the same achievement advantage over district schools that they did prior to the pandemic.[17] Ohio’s charter schools also remain less effective than those in states such as Massachusetts, New York, and Rhode Island. As of 2019, charter students in those states posted annual achievement gains equal to approximately 41, 75, and 90 extra days’ worth of learning each year, respectively. As I note above, however, as of 2022–23, the charter school advantage in Ohio equals approximately 13 additional days of learning in ELA (as compared to 28 days as of 2018–19) and 9 additional days of learning in math (as compared to 10 days as of 2018–19).

It may be that what has hindered Ohio charter schools is their limited funding compared to nearby district schools, which, among other things, has made it particularly difficult to recruit and retain teachers. Ohio’s substantial funding increases for high-quality charter schools in 2023–24 reduces the funding disparities significantly for these schools. Given what we know about the causal impact of funding increases when the money is spent well, these changes may enable significant improvements in the performance of Ohio’s charter schools.

Stéphane Lavertu is a Senior Research Fellow at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and Professor in the John Glenn College of Public Affairs at The Ohio State University. Any opinions or recommendations are his and do not necessarily represent policy positions or views of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, the John Glenn College of Public Affairs, or The Ohio State University. He wishes to thank Vlad Kogan for his thoughtful critique and suggestions, as well as Chad Aldis, Aaron Churchill, Chester E. Finn, Jr., and Mike Petrilli for their careful reading and helpful feedback on all aspects of the brief. The ultimate product is entirely his responsibility, and any limitations may very well be due to his failure to address feedback.

[1] The analysis focuses on “site-based” brick-and-mortar charter schools serving “general” or “special” education students. It excludes virtual schools and brick-and-mortar schools focused on dropout prevention and recovery, as there are no district schools comparable to these other types of charter schools.

[2] Ohio significantly increased charter school funding for the 2023–24 school year.

[3] This validation is based on studies that follow students who attended the same elementary schools and, upon reaching the terminal grade of that school, transitioned to charter and traditional-public middle schools. As I discuss below, such a “difference in differences” analysis—which must focus on middle schools—yields 2016-2019 results that are similar in magnitude to those presented in the analysis below.

[4] Within-district comparisons are particularly important in the wake of the pandemic, as recovery from learning loss varies significantly across districts. Indeed, as Table B5 and Table B6 in the appendix reveal, making statewide comparisons suggests that the value-added of charter schools has improved significantly since 2019.

[5] Reassuringly, the estimated effects of attending charter schools (as opposed to nearby traditional public schools) for 2018–19 are similar to those from my 2020 Fordham Institute report, which employs student-level data and, for middle schools, a rigorous “difference in differences” research design that yields plausibly causal estimates of charter school impacts. This correspondence speaks to the validity of SAS’s value-added calculations, which employ all prior years of available student test scores to generate a value-added score.

[6] The analytic sample includes “site-based” brick-and-mortar charter schools serving “general” or “special” education students. The analysis excludes virtual schools and brick-and-mortar schools focused on dropout prevention and recovery.

[7] Although composite estimates include value-added estimates for Integrated Mathematics I, Integrated Mathematics II, and ELA1, there are very few observations for these exams and they have relatively little bearing on the outcomes. The 2019 estimates capture the value-added estimates for schools in operation during the 2018–19 school year, and averages those schools’ value-added estimates across 2016–17, 2017–18, and 2018–19. This is the “three-year” value-added estimate that Ohio makes publicly available.

[8] The composite value-added measures are scaled the same way for pre-pandemic years (2018–19) and post-pandemic years (2021–22 and 2022–23), which enables straightforward pre- and post-pandemic comparisons. Figure 1 reveals a decline of 0.023 of a standard deviation in ELA achievement growth (over a 50 percent drop), but there is no decline in charter schools’ effectiveness (relative to nearby district schools) in mathematics or science.

[9] The estimate reaches statistical significance at the p=0.05 level for a one-tailed test but not a two-tailed test, which is the stricter threshold used in this report. However, given that the purpose of this analysis is to determine whether charter schools continue to outperform nearby district schools, then a one-tailed test is arguably the appropriate threshold to apply.

[10] These results appear in Table B4 of Appendix B. Note that the effect sizes for ELA and math are approximately twice as large as those reported in Figure 1, as the “effect sizes” on Ohio’s school report cards are scaled by the distribution of test-score growth, as opposed to the distribution of test scores. Scaling these estimates by the student achievement distribution reveals an overall charter school advantage of approximately 0.017 student-level standard deviations across all subjects combined, based on Ohio’s overall “composite” value-added measure.

[11] Hill et al. (2007) find that students typically experience annual achievement gains of 0.286 of a standard deviation in reading and 0.369 of a standard deviation in math in grades 4-10. Dividing the estimates in Figure 1 by these typical growth rates yields the fraction of a school year, which one can multiply by 180 (the typical number of instructional days in a school year) to get annual days’ worth of additional learning.

[12] Unlike the two-year composite estimates on Ohio’s school report cards—which pool these years such that 2022–23 gets twice as much weight as 2021–22 estimates—the analyses in Figure 2 and Figure 3 weight 2021–22 and 2022–23 estimates equally. Putting more weight on 2022-23 increases estimated charter school effectiveness relative to district schools.

[13] In the interest of space, the figure omits results for exams that few students took (ELA 1, Integrated Mathematics I, and Integrated Mathematics II) but that are accounted for in the composite estimates.

[14] For example, students who took the ELA2 high school exam in grade 10 during the 2018– 19 school year posted scores that were 0.09 of a standard deviation greater than we would have predicted based on their performance as of grade 8. In this case, the (statistically insignificant) impact estimate of 0.09 for ELA2 roughly translates to a value-added estimate of 0.045 standard deviations per year (learning in grades 9 and 10). This is comparable to the annual estimated ELA effect for grades 4–8 in 2018–19 of 0.033. In other words, the results in Figures 2 and 3 indicate that as of the 2018–19 school year, the achievement gains in ELA relative to district students were similarly large in grades 4–8 and high school, even though the estimates in Figure 3 make the high school estimates appear much larger.

[15] Although the by-year estimates yield primarily statistically insignificant results, the estimated differences between years sometimes attain or nearly attain conventional levels of statistical significance.

[16] It is not significant at the p<0.05 level for a two-tailed test, but it attains statistical significance for a one-tailed test.

[17] Within-district comparisons are particularly important in the wake of the pandemic, as recovery from learning loss varies significantly across districts. As Table B5 and Table B6 in the appendix reveal, making statewide comparisons suggests that the value-added of charter schools has improved significantly since 2019. However, that might be due to the intensive efforts to address learning loss in districts where charter students attend school.