In a recent Columbus Dispatch op-ed, Democrat state senator Bill DeMora slammed his GOP colleagues for supporting school choice, accused Ohio of having a “chronically underfunded” education system, and even suggested that Buckeye schools have markedly declined in national rankings over the past decade.

To its credit, the Dispatch quickly ran strong responses from Republican state senator Andrew Brenner and the Buckeye Institute’s Greg Lawson. They refute the “underfunding” exaggeration by noting a decade-worth of spending increases for K–12 education, including the hefty billion dollar hike passed in the most recent state budget bill. Senator Brenner also mentions the huge funding advantage enjoyed by traditional public schools—which spent on average $15,427 per pupil last year—when compared to private-school scholarship amounts, which generally range from $6,100 to $8,500.

These rejoinders cover the most egregious misstatements in the original column. But there is one more tall tale worth dispelling: that Ohio’s national ranking has fallen dramatically over the past decade and has slumped to the bottom half of states. As Senator DeMora declared in his piece, “Ohio used to be 5th in the nation when it comes to education. Since Republicans have taken over, we’ve fallen to 29th.”

This partisan talking point has circulated for years, and my former Fordham colleague Jamie Davies O’Leary has previously explained why it’s so misleading. In essence, back in 2010, the national publication Education Week awarded a 5th-place ranking to Ohio in its review of state education systems. That ranking quickly fell, but not because Ohio students were learning less or schools were becoming worse. Rather, it reflected an overhaul of the publication’s evaluation metrics. Starting in 2015, Ohio no longer received credit for its strong standards and accountability system, as EdWeek dropped measures that examined whether states had certain policies on the books.

Beyond this methodological change, EdWeek’s current rating system includes some dubious measures. They award credit to states based on the education levels, employment rates, and annual incomes of adult (!) populations. It also favors states that spend extraordinary sums on education, without consideration of whether dollars are well-spent. (Other analysts have also noted these flaws, too.) Overall, it’s little surprise that the top five states in its 2021 analysis were New Jersey, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maryland, and New York—all extremely high-spending East Coast states with more affluent adult populations (Ohio clocked in at 21st).

If not EdWeek, how should we gauge Ohio’s national standing? Actual student achievement seems like the place to go. On this count, the most respected yardstick is the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), often called the “Nation’s Report Card.” This biennial math and reading assessment is given to a representative sample of fourth and eighth students across the U.S. Unlike state exams, which differ across states, NAEP allows for state-to-state comparisons and national rankings.

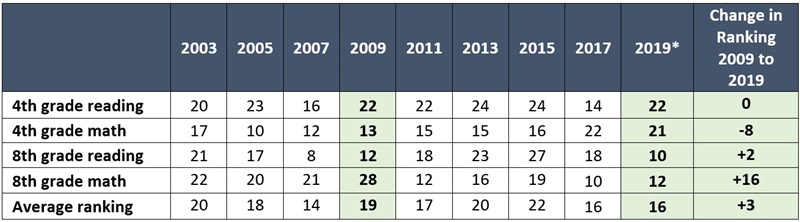

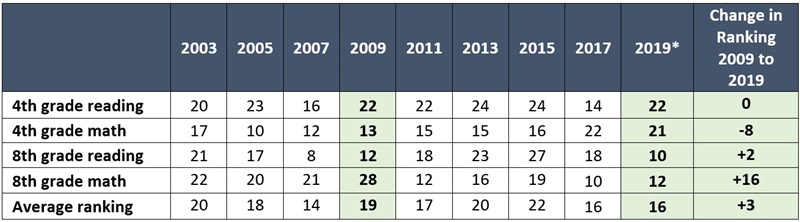

Table 1 shows Ohio’s rank on this assessment from 2003 to 2022. The first thing to note is that Ohio has never during this period scored among the nation’s top five states, so its 5th-place finish on EdWeek’s 2010 analysis was something of a mirage. The other thing to notice is the remarkable consistency in Ohio’s rankings during this period. In general, Ohio has placed between 10th and 20th in the nation, depending on the grade, subject, and year—not too shabby and hardly the freefall that some like to portray. When comparing 2009 to 2022 rankings, Ohio has ticked up (albeit very slightly) in three of the four assessments, and the state’s average ranking across the four exams is unchanged at 16th place.

Table 1: Ohio’s ranking on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)

Source: NAEP Data Explorer. Note: This table shows Ohio’s rank in comparison to all fifty states, Washington D.C., and the U.S. Department of Defense schools (fifty-two jurisdictions in all).

Source: NAEP Data Explorer. Note: This table shows Ohio’s rank in comparison to all fifty states, Washington D.C., and the U.S. Department of Defense schools (fifty-two jurisdictions in all).

Table 1 presents raw achievement rankings, which reflect, to a certain extent, the student demographics of each state. To gauge Ohio’s national standing after accounting for demographics, we take a look at the Urban Institute’s adjusted rankings based on NAEP results. On this measure, Ohio’s rankings tend to tick down slightly, but the overall picture is largely the same—the state usually lands somewhere between 15th and 20th in the nation, with an average ranking of 16th across the four assessments in 2019, the most recent from the Urban Institute.

Table 2: Ohio’s demographically-adjusted ranking on NAEP

Source: Urban Institute. Note: This table shows Ohio’s rank in comparison to all fifty states (excluding Washington DC and Department of Defense schools). (*) The Urban Institute has not updated its rankings for 2022.

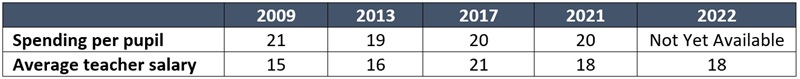

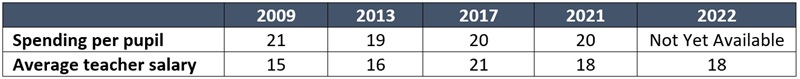

Source: Urban Institute. Note: This table shows Ohio’s rank in comparison to all fifty states (excluding Washington DC and Department of Defense schools). (*) The Urban Institute has not updated its rankings for 2022.Some may still wonder where Ohio ranks on “input”-type measures, such as school spending or teacher salary. Is Ohio falling behind on these metrics? As Table 3 indicates, the answer is no. Ohio’s rank on spending per pupil has held steady over the past decade, right around 20th in the nation. As for average teacher salary, Ohio has ranked from 15th to 21st in the nation. And that’s without considering Ohio’s relatively low cost of living, meaning that dollars for schools and teachers go further than they do on the coasts.

Table 3: Ohio’s national rank in spending per pupil and teacher salary, 2009 to 2022 (selected years)

Source: U.S. Department of Education, Digest of Education Statistics, Table 236.65 (spending per pupil) and Table 211.60 (teacher salary). Note: This table shows Ohio’s rank in comparison to all fifty states plus Washington D.C. (51 jurisdictions in all). The most recent year of national data for these measures are displayed.

Source: U.S. Department of Education, Digest of Education Statistics, Table 236.65 (spending per pupil) and Table 211.60 (teacher salary). Note: This table shows Ohio’s rank in comparison to all fifty states plus Washington D.C. (51 jurisdictions in all). The most recent year of national data for these measures are displayed.

In sum, one can say with confidence that Ohio ranks in the top half of states in K–12 education. The state isn’t in the bottom half nationally, as Senator DeMora implied, and it hasn’t been that low at any point within the past decade.

Of course, that doesn’t mean Ohio should stop striving to do better by its students. There’s no reason why the state couldn’t regularly crack the top ten nationally on NAEP, or even rise to the top spot. Achievement gaps remain unacceptably wide, and much work remains to narrow them. Ohio lawmakers are right to look for ways to continue to improve education in Ohio. But they should do so based on the facts, not outdated rhetoric.