Ohio education leaders hear special ed improvement recommendations

Nate Levenson presents ideas on special education reform

Nate Levenson presents ideas on special education reform

Last week, Fordham and the ESC of Central Ohio welcomed Nate Levenson to the Buckeye State for a series of conversations with district and Educational Service Center superintendents, state policymakers, and education organizations that represent both traditional districts and charter schools. Levenson spoke about his ideas for making special education more efficient and of greater quality, which are laid out in his recent report Applying Systems Thinking to Improve Special Education in Ohio.

Throughout his time in Ohio, Levenson emphasized the following points:

1. The compliance-driven culture of special education needs to change. Compliance is ingrained deeply into the culture of special education. Because compliance is so worrisome for special education directors, it leads to perverse incentives; for example, the incentive to “over-identify” students as special needs and the incentive for special education training and professional development to focus on compliance rather than pedagogy and actual student learning.

2. Schools could become more efficient and provide higher-quality services by subcontracting special education services. Ohio’s Educational Service Centers, social service agencies, and non-profit and for-profit companies could provide a “dream team” of special education specialists that districts could bid for. Districts would therefore reduce the in-house cost of providing special education services by contracting these services to other partners.

3. Identifying kids as special needs doesn’t necessarily translate to better outcomes. When students are unnecessarily identified as special needs, it lowers expectations and may lead to educational complications, in the long-term. One example Levenson gave (and the people he met agreed with) happens when students who have special needs go to college. While in high school, too many of these students become dependent on the personalized attention called for in IEPs, yet once in college, they lose the personalized help and struggle to learn independently. Many, as a result, dropout.

It is clear that school leaders are struggling with how to improve special education outcomes, while also containing the steadily rising cost of serving special needs students. It is also clear that many of them are open to a new way of doing things and Levenson’s overall message resonated well: Sharing and collaboration can lead to win-wins for the stakeholders in special education, and most importantly it can lead to better services for some of our most vulnerable kids.

For more info on solutions to reform Ohio special education, download the report by clicking cover page below.

With the Kasich Administration’s push for improved literacy skills among Ohio’s elementary students, many educators and analysts are keeping a keen eye on the development and assessment of reading programs. One national program, Project Sit Together and Read (STAR), is examined in the new research study by Shayne Piasta, Increasing Young Children’s Contact with Print during Shared Reading: Longitudinal Effects on Literacy Achievement. Piasta’s research measures the program’s effects on student literacy in pre-k to second grade. (See the U.S. Department of Education's review of the study.)

Project STAR is designed to develop students’ reading, spelling, and vocabulary skills. Teachers read aloud to students, but also use techniques to encourage kids to pay attention to the print on book pages. For example, a teacher may ask students about words or use a finger to follow along as words are read.

To measure the impact of these print focused techniques, researchers compared three groups in 85 preschool classrooms, composed mostly of socioeconomically disadvantaged students. One group received “high-dose” instruction, where Project STAR techniques were used in 120 reading sessions; the second “low-dose” group had just sixty reading sessions; the last group received regular instruction techniques. All groups received their instruction from the same books over a 30 week period.

The results are not surprising. When compared, students in the high-dose group had higher spelling abilities than those in the regular instruction group after two years. This can be expected, since practice and repeated exposure sharpen retention. What is interesting—and what Ohio educators should pay special attention to—is that students from the low dose group showed no vocabulary, reading, or spelling differences from those in the regular instruction group. In other words, simply presenting an intervention to kids means little if it is not effectively administered. Districts must be mindful of the rigor and the time spent in the program when developing early-childhood literacy initiatives.

SOURCE: WWC Review of the Report: Increasing Young Children's Contact with Print during Shared Reading (Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, October 2012).

The day after Superintendent Gene Harris announced her 2013 retirement from the Columbus City Schools (CCS) last month, Mayor Michael Coleman declared he’d play a greater role in improving the city’s schools. The district has been plagued in recent months by a data-tampering scandal and its unrelenting news coverage, and academic achievement has been stagnant for several years now. Coleman and City Council President Andrew Ginther have launched what is effectively the start of the post-Gene Harris era with a briefing about the district from Eric Fingerhut, corporate Vice President of Battelle's Education and STEM Learning business and the Mayor’s newly appointed education advisor; Mark Real, founder of KidsOhio.org; and John Stanford, deputy superintendent of CCS. The briefing is one of four intended to bring city leaders up to speed on the state of the city’s schools and related issues.

So what did they learn? There were at least three major takeaways.

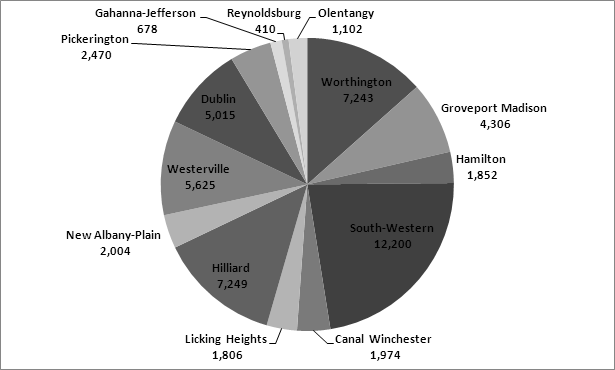

The city’s footprint is significantly larger than the district’s. The distinction between kids who live in the City of Columbus and those who live within the boundaries of Columbus City Schools (CCS) is important – and something most residents and observers would find surprising. Columbus’s population has doubled since 1950 and the region continues to grow. But much of the growth has happened in parts of the city not served by CCS. Real reported that 131,000 K-12 students live in the city; however, just 49,000 attend CCS. About 13,000 attend a charter school and roughly the same number attends a private school (another 2,400 use a voucher to attend a private school). But the biggest chunk of students attends one of 14 suburban school districts. Fully 49,600 city students go to school in the suburbs. Chart 1 shows the distribution of these students among those 14 districts.

Chart 1. Enrollment of City of Columbus resident students by suburban district, 2010-11

Source: KidsOhio.org

More striking than these numbers are the percentages of students in suburban districts who live in the City of Columbus. Following are the percent of each district’s student body that live in the City of Columbus (from highest to lowest): Worthington: 80 percent, Groveport Madison: 75 percent, South-Western: 63 percent, Hamilton: 62 percent, Canal Winchester: 57 percent, Licking Heights: 53 percent, Hilliard: 49 percent, New Albany-Plain: 48 percent, Westerville: 40 percent, Dublin: 37 percent, Pickerington: 24 percent, Gahanna-Jefferson: 10 percent, Reynoldsburg: 7 percent, and Olentangy: 7 percent.

When Mayor Coleman announced his new focus on education, he was quick to say he wouldn’t seek mayoral control of the schools. These data show, in part, why: Nearly 40 percent of his city’s K-12 students – and their families – aren’t served by Columbus City Schools.

Student achievement is lagging, though the district is fighting an uphill battle. With the state’s third-grade reading guarantee looming next school year, Real shared that 39 percent of the district’s third graders didn’t pass the state reading test in 2011 (recently released data show that 43 percent failed the exam in 2012). If the guarantee were in place, those students (with some exceptions) would not have been promoted to fourth grade. The district is working to improve early reading intervention so that pass rates improve, but teachers are fighting an uphill battle.

Thirty-four percent of kindergartners entering CCS in the 2010-11 school year were not kindergarten-ready, according to the state’s required literacy assessment. This rate is on par with Ohio’s other major urban districts; however, it is several times the rate in most of the county’s districts – with notable exceptions: South-Western City Schools, Groveport Madison Schools, and Whitehall City Schools all had higher percentages than Columbus of kindergartners who weren’t ready for school.

This news isn’t all bad. Stanford shared that of kindergartners who participated in the district’s preschool program, 89 percent are “kindergarten ready.” The school board is currently debating expanding the program to serve 1,500 more students.

Too many students aren’t graduating, and post-secondary supports are needed for those who do. The district’s five-year graduation rate is 78 percent, ten points lower than any other district in the county and fifth among the Big Eight districts. Likewise, CCS’s college-going rate is low: For the class of 2009 (the most recent year for which data are available), just 51 percent of graduates enrolled in a post-secondary program that fall, and 66 percent enrolled within two years of graduating.

On the upside, Stanford reported that among those CCS graduates who complete their freshman year of college, about 75 percent matriculate to sophomore year. Real and Stanford agreed that district, higher education, and community efforts to get students into college – and support them once there – are vital to increasing the number of college-educated adults in the area. The Central Ohio Compact, a coalition of education and community leaders, has set the goal of increasing the percent of Franklin County adults who have earned a post-secondary credential from 44 percent to 60 percent by 2025.

The next briefing will be held tomorrow at 6 p.m. at Columbus Downtown High School and focus on central Ohio workforce trends and how well the district is preparing students for jobs.

You may access the full briefing materials at mayor.columbus.gov/education.

On October 17, the State Board of Education authorized the Ohio Department of Education to release additional data components of a local school districts’ Report Card, in spreadsheet format. Until the Auditor of State completes his investigation of districts and buildings that are suspected of tampering student attendance records, the data remain “preliminary.” ODE therefore has not yet published an official Report Card for any district in its usual PDF format.

Despite the continuing cloud of suspicion over a few schools’ academic data, we believe that the preliminary data is sufficiently reliable to analyze district and charter school performance in Cleveland and Columbus (Ohio’s largest cities) and Dayton (Fordham’s hometown).

Check out our reports, which answer the following questions (among others):

The reports can be accessed through the hyperlinks on each city name: Cleveland, Columbus, and Dayton.

Last week, Fordham and the ESC of Central Ohio welcomed Nate Levenson to the Buckeye State for a series of conversations with district and Educational Service Center superintendents, state policymakers, and education organizations that represent both traditional districts and charter schools. Levenson spoke about his ideas for making special education more efficient and of greater quality, which are laid out in his recent report Applying Systems Thinking to Improve Special Education in Ohio.

Throughout his time in Ohio, Levenson emphasized the following points:

1. The compliance-driven culture of special education needs to change. Compliance is ingrained deeply into the culture of special education. Because compliance is so worrisome for special education directors, it leads to perverse incentives; for example, the incentive to “over-identify” students as special needs and the incentive for special education training and professional development to focus on compliance rather than pedagogy and actual student learning.

2. Schools could become more efficient and provide higher-quality services by subcontracting special education services. Ohio’s Educational Service Centers, social service agencies, and non-profit and for-profit companies could provide a “dream team” of special education specialists that districts could bid for. Districts would therefore reduce the in-house cost of providing special education services by contracting these services to other partners.

3. Identifying kids as special needs doesn’t necessarily translate to better outcomes. When students are unnecessarily identified as special needs, it lowers expectations and may lead to educational complications, in the long-term. One example Levenson gave (and the people he met agreed with) happens when students who have special needs go to college. While in high school, too many of these students become dependent on the personalized attention called for in IEPs, yet once in college, they lose the personalized help and struggle to learn independently. Many, as a result, dropout.

It is clear that school leaders are struggling with how to improve special education outcomes, while also containing the steadily rising cost of serving special needs students. It is also clear that many of them are open to a new way of doing things and Levenson’s overall message resonated well: Sharing and collaboration can lead to win-wins for the stakeholders in special education, and most importantly it can lead to better services for some of our most vulnerable kids.

For more info on solutions to reform Ohio special education, download the report by clicking cover page below.

With the Kasich Administration’s push for improved literacy skills among Ohio’s elementary students, many educators and analysts are keeping a keen eye on the development and assessment of reading programs. One national program, Project Sit Together and Read (STAR), is examined in the new research study by Shayne Piasta, Increasing Young Children’s Contact with Print during Shared Reading: Longitudinal Effects on Literacy Achievement. Piasta’s research measures the program’s effects on student literacy in pre-k to second grade. (See the U.S. Department of Education's review of the study.)

Project STAR is designed to develop students’ reading, spelling, and vocabulary skills. Teachers read aloud to students, but also use techniques to encourage kids to pay attention to the print on book pages. For example, a teacher may ask students about words or use a finger to follow along as words are read.

To measure the impact of these print focused techniques, researchers compared three groups in 85 preschool classrooms, composed mostly of socioeconomically disadvantaged students. One group received “high-dose” instruction, where Project STAR techniques were used in 120 reading sessions; the second “low-dose” group had just sixty reading sessions; the last group received regular instruction techniques. All groups received their instruction from the same books over a 30 week period.

The results are not surprising. When compared, students in the high-dose group had higher spelling abilities than those in the regular instruction group after two years. This can be expected, since practice and repeated exposure sharpen retention. What is interesting—and what Ohio educators should pay special attention to—is that students from the low dose group showed no vocabulary, reading, or spelling differences from those in the regular instruction group. In other words, simply presenting an intervention to kids means little if it is not effectively administered. Districts must be mindful of the rigor and the time spent in the program when developing early-childhood literacy initiatives.

SOURCE: WWC Review of the Report: Increasing Young Children's Contact with Print during Shared Reading (Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, October 2012).