Ohio’s list of challenged school districts is growing…a lot

Each year, the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) releases a “challenged district list.” The list, based on criteria outlined in state law, determines in which of the s

Each year, the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) releases a “challenged district list.” The list, based on criteria outlined in state law, determines in which of the s

Each year, the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) releases a “challenged district list.” The list, based on criteria outlined in state law, determines in which of the state’s 608 school districts a new charter school can open. In the waning days of 2018, ODE released the latest and greatest version of the list.

After reviewing the list, here are a few takeaways worth noting.

It’s five times longer than it was last year

Last year, only forty-two districts were identified as “challenged.” But this year, 218 districts—over one third of the state’s traditional public school districts—have met the state’s criteria. Some of the districts on the list aren’t a surprise given their chronically low performance. For instance, even if state law didn’t mandate their inclusion, all of the Big Eight districts (Akron, Canton, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, Toledo, and Youngstown) would have made the list based on their overall grades. Lorain City Schools, which is under the aegis of an Academic Distress Commission (ADC) because of chronic underperformance is included, as are the districts that could soon find themselves under ADC control—inner-ring, high-poverty suburbs like East Cleveland, Warrensville Heights, and Trotwood-Madison. But there are also many districts on the list that aren’t considered chronic low performers. Quite a few of them posted decent—even good—overall grades in 2018, but got tripped up by poor value-added grades in two of the three most recent years. Make no mistake: The dramatic increase in the number of districts on the list is likely to garner a lot of attention.

We’re not going to see an influx of new charters this year

With over one third of the state’s districts on the list, one might expect to see a flood of new charter school openings in areas where they were previously prohibited. In practice, though, things are a bit more complicated. The list greatly expands the districts where a charter school can open in the 2019–20 school year, but because it wasn’t official until December, potential new charter schools will have a very short timeframe in which to complete all the requirements for opening a new school. That includes finding a sponsor, locating and furnishing a facility, hiring staff, purchasing curricula and materials, and recruiting and enrolling students. As anyone who’s opened a new school can attest, it would be very difficult if not impossible to do all of that between December and August. The bottom line is that, even with a whopping 218 school districts on the challenged list, it’s unlikely we’ll see a flood of new charters opening this fall.

It’s bad policy and should be changed

Even though it’s unlikely any new charters will open this fall in newly eligible areas, there will still be some panic about the fact that the list has grown exponentially. Anti-choice folks won’t be shy in arguing that the list is just another example of how the state uses accountability policies to “punish” traditional districts. That’s what happens when state law pits district and choice programs against each other and makes the poor performance of one sector a “win” for the other. As long as school choice in Ohio is tied to the performance of traditional public schools, tension between the sectors will continue to grow.

That’s why the best path forward is to eliminate the challenged district designation all together and allow charters to open anywhere there is parental demand and educator interest. In its current format, the list creates nothing but tension: districts feel shamed, angry, or both when they’re included, and charters are frustrated that they’re consistently and severely limited regardless of which districts are identified. Removing geographic barriers to charter locations won’t be viewed as a win for districts, since they generally view any type of competition as negative. But it would eliminate a policy that recently labeled more than a third of them “challenged.” And even with wide-open borders, charters would still have plenty of hoops to jump through before they could open. They would also remain constrained by strict, charter-only accountability policies that have limited their growth in the past—policies like automatic closure and the sponsor evaluation system.

Most importantly, though, ditching the challenged district designation would open previously closed doors to thousands of Ohio families. There will always be families who need school choice because their assigned school district is poor performing. But poor performance isn’t the only reason families exercise school choice. Choice is about giving families the opportunity to send their child to whatever school will best meet their student’s needs. If there’s demand for more options, then more options should be available—regardless of how the local district performed on state report cards.

With Ohio’s safe harbor provisions now in the rearview mirror, formal consequences for poor school ratings have reemerged. Among them is the automatic closure law, first enacted in 2006, which requires low-performing charter schools to permanently close. Recently, the Ohio Department of Education released data revealing that fifty-two of Ohio’s 311 charter schools are at-risk of closure under this statute (including one sponsored by our sister organization, the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation). Taken together, the schools on this “watch list” enrolled 15,557 students last year, about the size of the Dayton Public School District. Charters are in jeopardy of closure when assigned F’s on specific measures—e.g., performance index and value added—based on their most recent data; schools must close when they receive two years of low ratings within a three-year window.

There are rumors about efforts to roll back the automatic closure statute. That’s not surprising given the severity of the penalty and the sharp rise in the number of charters in jeopardy of closure. As my former colleague Jamie Davies O’Leary has reported, only four schools sat on the watch list in the year prior to safe harbor. While not every school on the current watch list will close—some will post higher ratings this year—even twenty to thirty closures would be far higher than in the pre-safe-harbor era. From 2008–09 to 2013–14, a total of twenty-four charters—an average of four per year—closed under the law.

What to do? Two key questions should be raised before arriving at a conclusion. First, why are there so many more charters on this year’s watch list? There are two principal explanations, neither of which indicate deteriorating charter quality but are instead related to shifts in state accountability policies.

1) Dropout recovery charters were not previously subject to automatic closure but now are. In conjunction with the creation of an alternative rating system, lawmakers in 2012 removed the exemption from the automatic closure law previously given to dropout-recovery charter schools.[1] Eighteen dropout-recovery schools landed on this year’s closure list, and with tougher dropout-recovery standards on the horizon, more may fall prey to automatic closure in the coming years.

2) Performance index ratings, one of the key closure criteria, are lower today due to higher proficiency standards. Generally, most elementary and middle school charters are subject to closure when they receive two years of F’s on the performance index and the value-added-progress component within a three-year period.[2] However, these criteria were created prior to accountability transitions that began in 2014–15. While policymakers were right to strengthen state exams and proficiency standards, doing so depressed proficiency-based ratings such as the performance index. In 2013–14, prior to the transition, the statewide performance index score was 96.8. In 2017–18, it had sunk to 84.2.

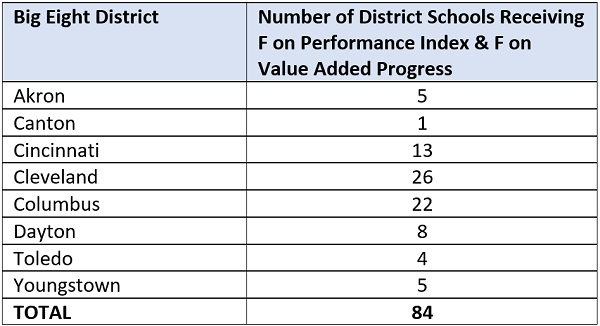

There has also been a huge jump in the number of F’s in the Big Eight urban areas where most charters are located. In 2013–14, just forty schools in these cities (both district and charter) received F’s on the performance index; that number now stands at 211. Though not a perfect estimation, table 1 illustrates that, akin to their charter counterparts, dozens of Big Eight district schools would likely be on the chopping block under today’s tougher standards if they faced an automatic closure penalty—but no such law exists for districts.

Table 1: Big 8 district schools receiving F’s on performance index and value-added progress (2017–18)

Source: Ohio Department of Education, Download Data. Note: This data is not an exact determination of district schools that would be at-risk of closure under the charter law. It includes some high schools that would be evaluated under slightly different criteria (e.g., F overall and F value-added progress); moreover, the value-added measure itself differs for the purposes of determining charter closures (it relies on a one-year value-added score, instead of a three-year average score, which is used to generate report card ratings, and it excludes some highly mobile students).

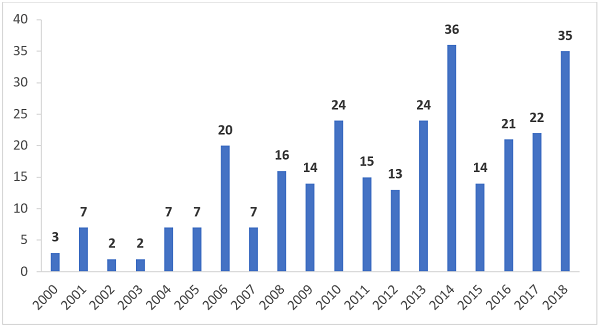

The second question is whether automatic closure remains a necessary policy tool, given the major charter policy improvements the legislature put in place in recent years. Specifically, the implementation of a sponsor evaluation system has put pressure on sponsors—the entities charged with school oversight—to close low-performing schools. Back in 2006, when the closure law initially passed, no evaluation system existed. There was little pressure on sponsors to consider performance factors in regard to closure, and they had a financial incentive to keep as many schools open as possible. That changed in 2013 when the legislature created an evaluation system designed to incentivize quality sponsorship practices, including closing schools that consistently miss performance targets. Two years later, this system was further sharpened with the passage of House Bill 2 in which lawmakers introduced stiffer penalties for ineffective and poor sponsor ratings. Overall, this accountability lever has led to the closing of numerous low-performing charters—even during the recent period of safe harbor, as figure 1 below indicates.

Figure 1: Charter closures by year, FYs 2000–18

Sources: Data for FY00–17 are based on Jamie Davies O’Leary’s calculations. For FY18, I used ODE’s closure list. Note: Six of the FY18 closures are reported as mergers with another school.

***

We’re entering a time period where the state’s more stringent accountability policies have put more charters in jeopardy of automatic closure than ever before—likely more than originally intended under the closure law. And due to recent reforms, charter sponsors themselves are now more likely to shutter low-performing schools. Based on the latter conclusion, one could make a good case for repealing the closure law. In my view, however, retaining a fail-safe that ensures students don’t wind up in chronically failing schools is prudent policy. Much is at stake for Ohio’s kids, and they can’t afford to spend years in abysmal schools, especially if superior options exist. (This should apply to districts, too!)

Yet lawmakers should revise the closure criteria so that the “death penalty” applies only in the most extreme cases. The current metrics upon which closures are determined—the overall, performance index, and value-added progress ratings—make good sense because they are key indicators of pupil achievement and growth. But closing schools based on just two years of ratings is a quick hook. In fact, the original closure law premised closure on either three or four consecutive years of poor performance, depending on grade span, with the shift to two years occurring in 2009. That may have been a sensible standard during an era of low expectations, but now that the state has tightened standards, reverting to an approach requiring three years of poor ratings would be wise. This would allow schools time to implement turnaround efforts once they’ve been put on notice, and would ensure that the law only closes schools that are true, chronic failures.

Ohio has made great strides in strengthening accountability via its sponsorship system. The resumption of Ohio’s automatic closure law is another piece of the accountability puzzle, ensuring that the lowest-performing charters either improve or permanently close. Given the significant policy shifts since the enactment of the original closure law, legislators should revisit the state’s automatic closure criteria. As in baseball, it should be three strikes and you’re out.

[1] Only charters serving a majority of special-education students and schools in their first two years of operation remain exempt from automatic closure.

[2] State law specifies a few other conditions based, for example, on schools’ overall ratings that can trigger automatic closure.

NOTE: On Tuesday, January 22, 2019, we released a report entitled Shortchanging Ohio’s charter students: An analysis of charter funding in fiscal years 2015–17. This is an abridged version of the report’s introduction and conclusion. You can read the full report and findings here.

All students deserve equal access to an excellent K–12 education. Yet the quality of their educational opportunities shouldn’t hinge on zip codes, family backgrounds, or the type of school they attend. Sadly, due in part to polarizing politics, Ohio has long underresourced its public charter schools, shortchanging tens of thousands of needy students in the process and leaving them with uneven opportunities.

Fordham and others have taken pains through the years to document this injustice. Based on data from 2001–02, we published an analysis in 2004 revealing massive funding gaps in our hometown of Dayton. That analysis found that the city’s charters received about $3,000 per student less than the district. Unfortunately, the situation did not improve. Ten years later, using 2010–11 data, an analysis by funding expert Larry Maloney found charter funding gaps of a similar size.

States and cities with high-performing charter sectors typically combine strong oversight with sufficient funding. For many years, Ohio did neither very well. However, state lawmakers made much-needed reforms in 2015 that strengthen charter accountability—a critical first step in assuring sector-wide quality. But there have been no detailed analyses since the Maloney report that examines charter funding in Ohio.

Over his two terms, Governor Kasich made a variety of school funding changes and shifted toward a more student-centered approach. These changes impacted charter school funding as well, including a new (but modest) school-facilities program. Given these changes—and with Governor Mike DeWine taking the helm—a fresh look at charter funding equity is needed. Has Ohio cured its long-standing funding disparities? Or are charters still badly underfunded?

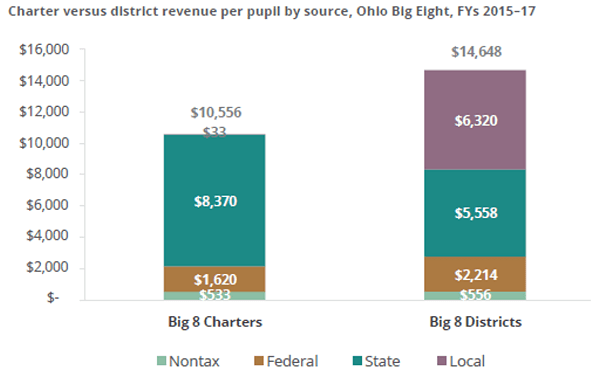

This study of charter funding reveals continuing inequities in the Buckeye State, the most troubling of which are found in the Big Eight cities.[1] According to my analysis, Big Eight charters receive on average $10,556 per pupil in total revenue versus $14,648 for the Big Eight districts during FYs 2015–17. These urban charters, then, face funding shortfalls of a staggering $4,092 per student, equivalent to receiving 28 percent less revenue relative to districts.

These figures reflect total revenue from all public sources (federal, state, and local) and nontaxpayer sources, with the vast majority of school revenues being generated through the public sources. Big Eight charters and districts receive nontaxpayer funding of roughly equal amounts ($533 and $556 per pupil, respectively); thus, the shortfall in charter revenues can be traced to disparities in public funding amounts, specifically a lack of local funding for charters, as the figure below illustrates.

These percentages, however, mask the true impact of these inequities: translated into dollar terms, Ohio shortchanged Big Eight charters of $253 million per year during FYs 2015–17—tens of millions of dollars that would have supported the needs of children, many of whom come from low-income families or are students of color.

Though some charters have produced exceptional results on shoestring budgets, such glaring inequities have consequences. Most troubling is that they rob children, many from low-income and minority families, of the educational opportunities they deserve. With less funding, charter students may not receive the one-on-one or small-group tutoring they need; they might have fewer opportunities to take art or music classes; and they may have less access to advanced or specialized coursework. Children attending public charter schools might have fewer opportunities for extracurricular activities that allow them to develop important intangible skills, and these funding shortfalls could make important health and social services out of reach for at-risk children.

Moreover, underfunding Ohio charters has systemic consequences, as well. For instance, charters often resort to paying teachers lower wages, leaving great instructors vulnerable to being lured away by districts that can offer more lucrative pay. Ohio charters also lack access to capital resources that enable them to build quality school facilities. In fact, Ohio charters often dip into their already thin operational budgets just to cover rental payments. Ohio’s inequitable funding system also yields an inhospitable location for charters to take root and serve more children in need of quality educational opportunities.

Recognizing both the moral imperative and practical need to fund charters fairly, several states have moved to strengthen charter funding. Just last year, Colorado and Florida passed legislation that now allow their charters to receive a portion of local tax revenue. Amid a major school-funding overhaul, Illinois also approved revisions ensuring that its charters will now receive the same operational funding as nearby districts.

Ohio lawmakers should follow in leading states’ footsteps. We acknowledge that achieving this goal is fraught with politics. But it’s important to keep two things in mind. First, we must make careful distinctions between brick-and-mortar and online charters. Site-based charters ought to be funded at parity with their nearest districts. E-schools are a completely different educational model, and legislators are already wisely considering alternative arrangements such as competency-based funding. Second, we must not forget that Ohio recently enacted strict charter accountability reforms that now ensure taxpayer dollars are being used responsibly to meet the needs of children and families. In fact, given the serious penalties for poor results, it’s fair to say that Ohio’s school-accountability policies are now tougher for charters than for districts. Within the past three years, more than seventy charters have closed—and more may shutter as the state’s automatic charter closure law goes back into effect after a period of safe harbor.

It will take courageous policy makers, of both political parties, to remedy charter funding inequity in Ohio. For state leaders who wish to act, we offer three concrete steps that would move Ohio toward fairer charter funding.

Shift Ohio to a direct-funding approach for charter schools. The pass-through mechanism by which the state currently transfers charter funds through districts is unnecessarily complex and leaves charters exposed to criticism by creating the false appearance that districts fund charters. So long as the state funds charters, Ohio should pay them directly out of the foundation appropriation in the state budget. Though this proposal would not resolve the funding gap, it would clear up confusion and be fairer to both district and charter schools.

Improve the support for facilities. On average, Ohio charters spend very little on capital investments that can help them serve future generations of students. And most charters continue to scrape by in rented space, typically paid out of their operational budgets. To improve facility support, state legislators should pursue two initiatives: First, they should boost the modest $200 per pupil facilities reimbursement to an amount more in line with such costs. Second, they should appropriate new money to the Community School Classroom Grant that provides aid to cover charters’ renovation and construction costs. In so doing, they should also broaden program eligibility so that more charters can apply for funding.

Ensure that brick-and-mortar charters receive operational funding on par with their nearest districts. Here, state lawmakers face two choices: either pony up more money from the state budget or require local school boards to share locally generated revenue with the charter schools in their boundaries, having all public funds truly “follow students.” On the first option—more state aid—legislators either could tie charter funding amounts to their nearest districts’ state and local revenues or they might introduce a multiplier—a “charter school weight”—that is added to the state’s base per-pupil amount of funding. For example, charters might receive 1.3 times a base amount of $6,010 per pupil, yielding a modified base of $7,813 per student. Alternatively, though likely to face political headwinds, lawmakers could simply require locally generated funds to follow children to charters—public schools serving students whose families also pay taxes to that district. Though very limited, there is precedent in Ohio for local tax-sharing agreements—one established in Cleveland—and state lawmakers could require, or incentivize, these types of arrangements.

Legislators on both sides of the aisle need to recognize that providing second-class charter funding simply isn’t fair to their students. Ohio is long past due in funding charters equitably, and much work remains.

[1] The Big Eight refers to Akron, Canton, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, Toledo, and Youngstown.

One of the longest running debates about early childhood education is how much emphasis teachers should place on academic content. Thanks to changing perceptions, the standards-based reform movement, and accountability policies that have changed early grade instruction, kindergarten classrooms are increasingly focused on academic content and skill development.

These changes have garnered mixed reactions. Those in favor of the increased academic focus cite studies showing that exposure to advanced content is associated with higher student achievement. Opponents, meanwhile, have raised questions about whether kindergartners are developmentally ready for academics, and whether focusing on more advanced skills reduces play opportunities and leads to poorer social-emotional (SE) development.

To address these concerns, a new study examines the relationship between advanced content in kindergarten and children’s academic achievement and social-emotional outcomes. The study’s authors used the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study of Kindergartners in 2010 (ECLS), a nationally representative study of kindergarteners enrolled during the 2010–11 school year. ECLS included approximately 18,200 children from nearly 1,000 schools, but the authors used a specific sample of 11,600 public school kindergarteners and their 2,690 teachers. ECLS collected information during the fall and spring of the academic year about children’s academic achievement and SE skills through surveys and interviews of parents and teachers, as well as math and ELA assessments. The authors control for class size, teacher characteristics, childcare situation, and a host of demographic and family background variables.

The authors defined advanced content as academic skills that were taught in a higher grade than kindergarten. Using the ECLS dataset, they identified which skills qualified as advanced based on the percentage of teachers who indicated that they were taught in a higher grade. They found four such skills in ELA and ten in math.

On average, teachers spent close to nine days per month on advanced ELA content and slightly more than six days per month on advanced math content. Yet the authors found no negative association between advanced content and SE skills. In fact, greater exposure to advanced math was related to some improved SE outcomes (though exposure to advanced content in ELA was unrelated to SE skills). And as expected, they found that more advanced content was correlated with higher test scores in the respective subjects.

It’s unclear why exposure to advanced math was positively associated with SE outcomes and exposure to advanced ELA content was not, but the authors offer a few theories. First, it’s possible that advanced math enhances executive functioning in a way that advanced ELA does not. Second, there may have been variations in what was considered challenging material in each subject. Moreover, these findings are in line with other research that didn’t find negative associations between challenging academic content and healthy SE development.

The authors do note several limitations of their study. First and most importantly, this study is correlational. There is the possibility of self-selection bias, and the authors can’t definitively say whether children’s gains were due to exposure to advanced content or exposure to highly effective teachers; teachers who are more likely to teach advanced content than their peers, for example, may also produce better achievement and SE gains.

With that said, the authors are “cautiously optimistic that advanced academic content can be taught without compromising students’ social-emotional skills.” The research is a promising sign that they’re right.

SOURCE: Vi-Nhuan Le, Diana Schaack, Kristen Neishi, Marc W. Hernandez, Rolf Blank, “Advanced Content Coverage at Kindergarten: Are There Trade-Offs Between Academic Achievement and Social-Emotional Skills?” American Educational Research Journal (January 2019).

In Ohio and across the nation, policymakers are contemplating sizeable increases to public outlays for early childhood programs, including expanded preschool, childcare, and other support services. Polls indicate that early childhood programs enjoy broad support, and proponents of early childhood programs often cite as evidence for expansion the positive, long-run effects of the boutique Perry Preschool program (it served just fifty-eight low-income children during the 1960s). But will greater expenditures in early childhood programs generate big returns? Or could they backfire?

A new study by university researchers Michael Baker, Jonathan Gruber, and Kevin Milligan offers a cautionary tale. They examine the short- and longer-run outcomes of children participating in North America’s largest universal childcare program. Starting in fall 1997, Quebec began offering large public subsidies, open to all parents, for center- or home-based childcare programs serving youngsters up to four years old. As of 2011–12, the program cost $2 billion per year and subsidized roughly 80 percent of a family’s child care costs. Quebec has been the only province to adopt such an expansive childcare policy. For example, from the mid-1990s to 2008, Quebec children in center-based childcare jumped from 10 to 60 percent; during that same period, the rise was just 10 to 20 percent in the rest of Canada.

The study examines both the immediate effects of the program on two- and three-year olds, as well as longer-run impacts for those exposed to the Quebec childcare program. Baker and colleagues examine a range of outcomes, including non-cognitive indicators based on surveys gauging parent perceptions about their child’s behavior; standardized exam results; health outcomes (self-reported in surveys by twelve- to twenty-year-olds); and criminal activity. To conduct the evaluation, they compare the outcomes of children exposed to the Quebec program to Canadian children who were not, while using statistical methods to control for various demographic differences.

First, the short-run findings on children in Quebec’s childcare program. Consistent with a prior analysis in 2005 from this research team, they find significant negative effects of universal childcare on young children’s non-cognitive outcomes in areas such as anxiety and aggression; they also uncover negative impacts on the only cognitive measure available, the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. Though not analyzed in this paper, Baker and colleagues cite other work showing that the negative results are driven by children from two-parent families who, on average, fare worse in the childcare program (disadvantaged children from single-parent families see improved outcomes).

Second, the study examines the longer-run outcomes. On non-cognitive measures, the analysts find persistent, negative effects. At ages five through nine, children exposed to the childcare program exhibited more aggression, anxiety, and hyperactivity and they were less likely to get along with their teacher. Meanwhile, on cognitive measures—national math, reading, and science exams given to thirteen- and sixteen-year-olds—the analysts find no clear impacts on test scores (the estimates are negative in all subjects but not statistically significant). However, the analysts do report a positive effect on the international PISA math exam, but no impacts in reading and science. The researchers conclude, “Overall the evidence on the long-run impact of the Quebec Family Plan on test scores is mixed.” As for health and criminal activity outcomes at ages twelve to twenty, the study uncovers negative results. In surveys, those exposed to the Quebec program reported worse physical health and life satisfaction, and an analysis of national crime data concludes that the program led to higher rates of criminal activity (both accusations and convictions).

All told, this research paints a sobering picture about how Quebec’s universal early childhood program has affected children, save perhaps for its least advantaged children who seem to have benefitted. The authors don’t speculate in this report on mechanisms driving the results, though in their previous evaluation they write, “We also find suggestive evidence that families we study became more strained with the introduction of the program. This is manifested in increased aggressiveness and anxiety for the children.”

Early childhood programs that target the neediest children likely make sense—such as Head Start or Ohio’s income-based Early Childhood Education Grant. Yet as this study suggests, policymakers and advocates of universal early childhood programs should also beware of the potential impacts to children when broad-based public subsidies shift the care of our youngest kids away from parents and more to professionals.

Source: Michael Baker, Jonathan Gruber, and Kevin Milligan, “The Long-Run Impacts of a Universal Child Care Program,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy (forthcoming). An open-access version is available here.