NOTE: On Tuesday, January 22, 2019, we released a report entitled Shortchanging Ohio’s charter students: An analysis of charter funding in fiscal years 2015–17. This is an abridged version of the report’s introduction and conclusion. You can read the full report and findings here.

All students deserve equal access to an excellent K–12 education. Yet the quality of their educational opportunities shouldn’t hinge on zip codes, family backgrounds, or the type of school they attend. Sadly, due in part to polarizing politics, Ohio has long underresourced its public charter schools, shortchanging tens of thousands of needy students in the process and leaving them with uneven opportunities.

Fordham and others have taken pains through the years to document this injustice. Based on data from 2001–02, we published an analysis in 2004 revealing massive funding gaps in our hometown of Dayton. That analysis found that the city’s charters received about $3,000 per student less than the district. Unfortunately, the situation did not improve. Ten years later, using 2010–11 data, an analysis by funding expert Larry Maloney found charter funding gaps of a similar size.

States and cities with high-performing charter sectors typically combine strong oversight with sufficient funding. For many years, Ohio did neither very well. However, state lawmakers made much-needed reforms in 2015 that strengthen charter accountability—a critical first step in assuring sector-wide quality. But there have been no detailed analyses since the Maloney report that examines charter funding in Ohio.

Over his two terms, Governor Kasich made a variety of school funding changes and shifted toward a more student-centered approach. These changes impacted charter school funding as well, including a new (but modest) school-facilities program. Given these changes—and with Governor Mike DeWine taking the helm—a fresh look at charter funding equity is needed. Has Ohio cured its long-standing funding disparities? Or are charters still badly underfunded?

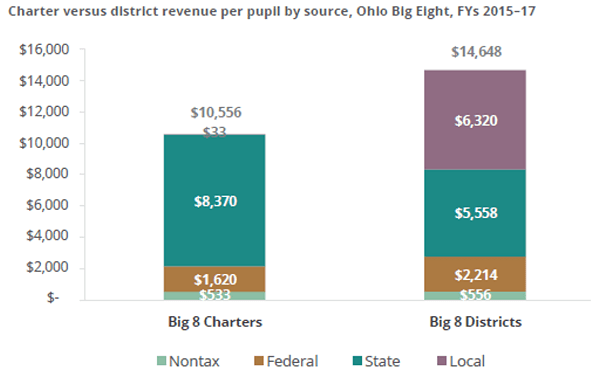

This study of charter funding reveals continuing inequities in the Buckeye State, the most troubling of which are found in the Big Eight cities.[1] According to my analysis, Big Eight charters receive on average $10,556 per pupil in total revenue versus $14,648 for the Big Eight districts during FYs 2015–17. These urban charters, then, face funding shortfalls of a staggering $4,092 per student, equivalent to receiving 28 percent less revenue relative to districts.

These figures reflect total revenue from all public sources (federal, state, and local) and nontaxpayer sources, with the vast majority of school revenues being generated through the public sources. Big Eight charters and districts receive nontaxpayer funding of roughly equal amounts ($533 and $556 per pupil, respectively); thus, the shortfall in charter revenues can be traced to disparities in public funding amounts, specifically a lack of local funding for charters, as the figure below illustrates.

These percentages, however, mask the true impact of these inequities: translated into dollar terms, Ohio shortchanged Big Eight charters of $253 million per year during FYs 2015–17—tens of millions of dollars that would have supported the needs of children, many of whom come from low-income families or are students of color.

Though some charters have produced exceptional results on shoestring budgets, such glaring inequities have consequences. Most troubling is that they rob children, many from low-income and minority families, of the educational opportunities they deserve. With less funding, charter students may not receive the one-on-one or small-group tutoring they need; they might have fewer opportunities to take art or music classes; and they may have less access to advanced or specialized coursework. Children attending public charter schools might have fewer opportunities for extracurricular activities that allow them to develop important intangible skills, and these funding shortfalls could make important health and social services out of reach for at-risk children.

Moreover, underfunding Ohio charters has systemic consequences, as well. For instance, charters often resort to paying teachers lower wages, leaving great instructors vulnerable to being lured away by districts that can offer more lucrative pay. Ohio charters also lack access to capital resources that enable them to build quality school facilities. In fact, Ohio charters often dip into their already thin operational budgets just to cover rental payments. Ohio’s inequitable funding system also yields an inhospitable location for charters to take root and serve more children in need of quality educational opportunities.

Recognizing both the moral imperative and practical need to fund charters fairly, several states have moved to strengthen charter funding. Just last year, Colorado and Florida passed legislation that now allow their charters to receive a portion of local tax revenue. Amid a major school-funding overhaul, Illinois also approved revisions ensuring that its charters will now receive the same operational funding as nearby districts.

Ohio lawmakers should follow in leading states’ footsteps. We acknowledge that achieving this goal is fraught with politics. But it’s important to keep two things in mind. First, we must make careful distinctions between brick-and-mortar and online charters. Site-based charters ought to be funded at parity with their nearest districts. E-schools are a completely different educational model, and legislators are already wisely considering alternative arrangements such as competency-based funding. Second, we must not forget that Ohio recently enacted strict charter accountability reforms that now ensure taxpayer dollars are being used responsibly to meet the needs of children and families. In fact, given the serious penalties for poor results, it’s fair to say that Ohio’s school-accountability policies are now tougher for charters than for districts. Within the past three years, more than seventy charters have closed—and more may shutter as the state’s automatic charter closure law goes back into effect after a period of safe harbor.

It will take courageous policy makers, of both political parties, to remedy charter funding inequity in Ohio. For state leaders who wish to act, we offer three concrete steps that would move Ohio toward fairer charter funding.

Shift Ohio to a direct-funding approach for charter schools. The pass-through mechanism by which the state currently transfers charter funds through districts is unnecessarily complex and leaves charters exposed to criticism by creating the false appearance that districts fund charters. So long as the state funds charters, Ohio should pay them directly out of the foundation appropriation in the state budget. Though this proposal would not resolve the funding gap, it would clear up confusion and be fairer to both district and charter schools.

Improve the support for facilities. On average, Ohio charters spend very little on capital investments that can help them serve future generations of students. And most charters continue to scrape by in rented space, typically paid out of their operational budgets. To improve facility support, state legislators should pursue two initiatives: First, they should boost the modest $200 per pupil facilities reimbursement to an amount more in line with such costs. Second, they should appropriate new money to the Community School Classroom Grant that provides aid to cover charters’ renovation and construction costs. In so doing, they should also broaden program eligibility so that more charters can apply for funding.

Ensure that brick-and-mortar charters receive operational funding on par with their nearest districts. Here, state lawmakers face two choices: either pony up more money from the state budget or require local school boards to share locally generated revenue with the charter schools in their boundaries, having all public funds truly “follow students.” On the first option—more state aid—legislators either could tie charter funding amounts to their nearest districts’ state and local revenues or they might introduce a multiplier—a “charter school weight”—that is added to the state’s base per-pupil amount of funding. For example, charters might receive 1.3 times a base amount of $6,010 per pupil, yielding a modified base of $7,813 per student. Alternatively, though likely to face political headwinds, lawmakers could simply require locally generated funds to follow children to charters—public schools serving students whose families also pay taxes to that district. Though very limited, there is precedent in Ohio for local tax-sharing agreements—one established in Cleveland—and state lawmakers could require, or incentivize, these types of arrangements.

Legislators on both sides of the aisle need to recognize that providing second-class charter funding simply isn’t fair to their students. Ohio is long past due in funding charters equitably, and much work remains.

[1] The Big Eight refers to Akron, Canton, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, Toledo, and Youngstown.