Challenging young men to excel academically

In Ohio’s great graduation debate, we at Fordham have

In Ohio’s great graduation debate, we at Fordham have

In Ohio’s great graduation debate, we at Fordham have warned that lowering the bar is tantamount to the “soft bigotry of low expectations.” Weakened standards, such as those pushed by the State Board of Education, imply that many low-income pupils need alternative routes to diplomas because they’re unable of reaching the state’s academic or career-technical requirements. Yet as this piece discusses, lowering our sights won’t just hurt poor students, it’ll also ask much less of our young men, especially Ohio’s young men of color.

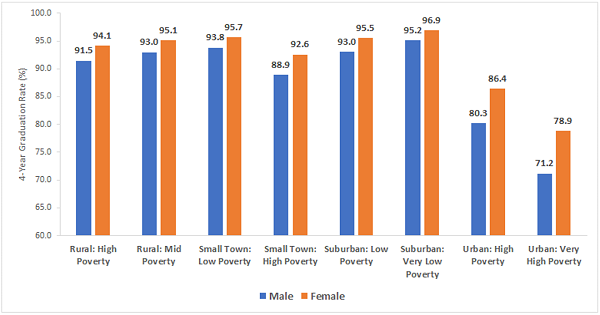

Consider the four-year graduation rates for the class of 2017, the most recent available, displayed in the figures below. This was the final cohort subject to Ohio’s “old” graduation requirements, which included passage of the low-level Ohio Graduation Tests (OGTs). Figure 1 shows average graduation rates across Ohio’s district typologies, classifications developed by ODE to group districts with similar socio-economic and geographic characteristics. You’ll notice that graduation rates for males trail behind their female counterparts across all typologies, suggesting that high-school completion for young men should be a widespread concern. The disparities are most visible in Ohio’s high-poverty urban areas that include big- and small-city districts, and some inner-ring suburbs.

Figure 1: Average four-year graduation rates across Ohio’s district typologies by gender, class of 2017

Note: In a number of districts, graduation rates are reported by ODE as “>95%”; in these cases, I impute 97.5 percent, the midpoint between 95 and 100 percent. Average graduation rates by typology are weighted by the number of students in each district’s graduating class. Graduation rates in Figure 1 and 2 do not include charter students.

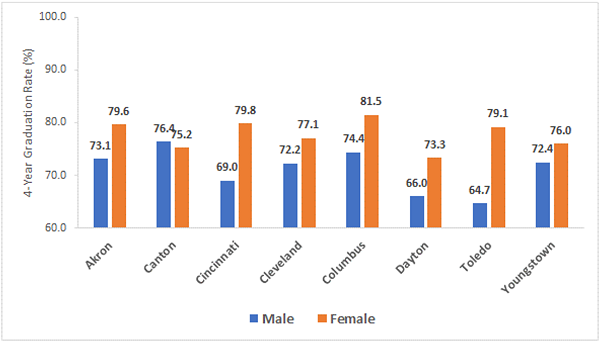

Figure 2 offers a closer look at graduation rates in Ohio’s big-city districts, known as the Big Eight. These districts comprise the “Urban: Very High Poverty” group in Figure 1 and educate a disproportionate number of low-income students and students of color. The chart below shows that, in seven of the Big Eight districts, male graduation rates fall behind. In Toledo, for instance, just 65 percent of young men graduate in four years, while 79 percent of young women do so—a 14 percentage point difference. In Cincinnati, the gap is 11 points; in Columbus, it’s 8; and in Dayton, it’s 7. The figure below also suggests that gender gaps within cities can’t be explained by poverty: Males from Toledo, for instance, likely come from similar economic backgrounds as girls—yet they graduate at much lower rates.

Figure 2: Four-year graduation rates across Big Eight districts by gender, class of 2017

The gender gap in graduation rates is troubling, but what can we make of it?

First, let’s applaud the achievements, depicted in these data, of Ohio’s young women. The decades-long push to strengthen girls’ educational opportunities has borne fruit, as they’ve motored past boys in not only high school graduation, but also college completion. As with efforts to narrow any type of achievement gap, including those displayed above, we shouldn’t lower the ceiling. Rather, the focus should be on efforts to raise the floor—in this case, improving the education of boys.

Second, we should consider the consequences of lower graduation rates for males. Lacking even high-school level competencies, low-skilled men are sure to face long odds of labor market success, likely resulting in menial jobs and bouts of unemployment. Such ramifications might spill over into other areas of their lives, including higher rates of divorce, depression, or incarceration.

Third, it’s worth thinking about why we see this gender gap. On one level, it simply reflects academic troubles. State exam results from the 2014–15, when the class of 2017 would’ve taken their OGTs, confirm that girls did better on reading and writing exams, though results in other subjects—math, science, and social studies—weren’t noticeably different. Of course, lower graduation rates also reflect higher dropout rates which may be tied to weaker non-academic competencies, such as self-discipline, that are needed to persist in high school.

One could ask more probing questions about why boys underperform. Non-schooling factors could certainly play a role: For instance, though still the subject of academic debate, it’s likely that boys are more adversely affected by family breakdown.

Yet schools themselves may be having a more difficult time educating boys. They are staffed primarily by women, even though research indicates that boys often achieve at higher levels when they have male instructors. There may be a cultural dimension as well in which scholastic achievement isn’t viewed as “masculine,” perhaps resulting in lower expectations for boys. As child psychologist Michael Thompson puts it: “Does being a good student make you a real man? I don't think so… It is not cool.”

It’s this last explanation that troubles me most in our debates over graduation requirements. Does championing low standards reinforce a repugnant idea that males, particularly young men of color, are unable to do well in school? Like overprotective parenting, does it shelter the young men who will be expected to lead as responsible heads of households? And will it leave many men without the knowledge and skills necessary to be reliable breadwinners?

In the short term, giving out diplomas will make everyone feel good by inflating graduation rates, including those of males. But this is the easy way out. It allows young men to bypass the hard work needed to prepare for life after high school, whether college, career, or the military. From the gridiron to the baseball diamond, we regularly challenge young men to work hard and do their best. Yet we expect so little of them in the classroom. Tragically, this way of thinking will only leave thousands more men behind.

Earlier this week, Republican candidate and current Attorney General Mike DeWine won the Ohio gubernatorial election by 4.2 percentage points over Democratic challenger Richard Cordray. DeWine will succeed two-term Republican governor John Kasich, whose leadership left an indelible imprint on Ohio’s education policies.

Although DeWine’s education policies won’t take shape until after the start of the new year when his administration unveils its first operating budget, there are plenty of clues about which issues will be priorities. Based on his campaign’s policy platform and various news sources, here’s a look at what can be expected from a DeWine administration.

Accountability and testing

The governor-elect is stepping into his position amidst some intense education debates. A dispute over high school graduation requirements has raged for over a year, with no end in sight. There’s been a consistent push to dump A-F letter grades on state report cards. And there is a lot of heated discussion, and ongoing litigation, about academic distress commissions—the state’s approach to intervening in persistently low-performing districts. And, yes, there continue to be concerns about “overtesting.”

Despite all this controversy, or perhaps because of it, DeWine was careful to leave himself plenty of wiggle room during the campaign. His education agenda did promise to “reduce the number of tests that students are required to take,” but he also told the media that part of his plan is “to not make too many changes, in order to bring some stability to Ohio’s school system.”

DeWine’s acknowledgement that Ohio’s education system is long overdue for some stability is likely welcome news for many teachers and administrators. But even if he changed his mind, his administration would be limited in how many and which tests it could cut. In Ohio, students take annual exams in grades 3–8 in math and English language arts (ELA), and science tests in grades five and eight. All these assessments are required by federal law. In high school, students take seven end-of-course (EOC) exams: two in ELA, two in math, two in social studies, and one in science. Federal law only requires one exam each in math, ELA, and science. That puts four of the EOC exams on the potential chopping block, but it’d be a shame to lose them since they were implemented in an effort to raise previously low expectations. There are also additional tests—like the statewide administration of the Kindergarten Readiness Assessment and SAT/ACT or the WorkKeys exam—that could be cut, though the information and benefits that these tests offer students, parents, and educators would make cutting them a potentially unwise move as well.

As for school report cards, DeWine has said very little other than calling for a report card that “parents can understand.” Of course, given the plaudits that Ohio’s report card has received, one could argue that’s already the case. He has told the media that he is interested in finding a way to support failing districts prior to the state receivership via academic distress commissions. And although he has not made his position on graduation requirements explicitly clear, his campaign spokesman has said that DeWine believes “we should set the goal that every high school graduate should either be college or career ready. They should be able to immediately pass college entrance exams or they should have a skill they leave school with.” That sounds far more like tweaks to Ohio’s existing graduation pathways than diplomas for good attendance and a part-time job.

School choice

School choice is a hot topic, too. Ohio has a rich and complex choice environment that includes public charter schools, vouchers, and open-enrollment. Although Governor-Elect DeWine did not include a formal position on school choice in his education platform, he has previously declared his support for choice, and his campaign spokesman confirmed that he believes parents should be able to choose their child’s school. Opponents went after DeWine for taking campaign contributions from the founder of ECOT, the now defunct online school, but as state attorney general, he also filed a lawsuit against ECOT to recover public funds. In his education platform, DeWine also called for the establishment of a pay-for-performance model for online schools. Given his previous support for school choice and his recent calls for more oversight, it’s reasonable to assume that DeWine will follow in Kasich’s footsteps by supporting high quality choice options.

School funding

DeWine’s education agenda promises that his administration will “create a more equitable funding system that directs state resources toward supportive services for children most in need.” Although there are no specific details, “supportive services” sounds a lot like wraparound services. His platform also claims that “funding is not about systems, it’s about students.” That statement is also pretty vague, though there’s a possibility that it indicates openness to a system where money follows the child and results in greater equity.

Early childhood education

DeWine’s campaign website has an entire page devoted to early childhood development. He plans to raise the eligibility level for publicly funded early childhood programs for working families from 130 percent of the federal poverty level to 140 percent, a change that could easily be included in his upcoming budget proposal. His policy platform also pledges to “ensure all early childhood education centers are high quality,” which could indicate that he plans to provide additional resources and incentives for centers to achieve a high quality rating.

Career and technical education

Proposals for how to expand and improve career and technical education (CTE)—which DeWine refers to as “vocational education” on his campaign website—make up a large chunk of his K–12 platform. Here are his most significant proposals:

As you can see, these proposals are wide-ranging and encompass more than just the K–12 sector. They also offer DeWine his biggest chance to leave a lasting educational legacy. CTE enjoys broad bipartisan support and, when done well, promotes cross-sector partnerships between businesses, secondary and postsecondary schools, and community organizations. By expanding and improving CTE offerings, the governor-elect could work with a diverse coalition of folks from across the aisle and a vast variety of sectors.

The federal government recently passed a new law governing CTE funding and implementation, but states won’t be required to submit their implementation plans until sometime next year. That gives the new governor a perfect opportunity to push for his ideas without causing too much disruption. He could also take advantage of the increased funding the law provides and save Ohio taxpayers some money. And since Ohio already has a thriving and robust CTE sector with plenty of reform and innovation already underway, he won’t have to start from scratch to do any of it.

***

According to his education agenda, the goal of the DeWine administration is “educational excellence in every school, for every student.” Although smart and well-intentioned people will disagree on how to make that vision a reality, many of the ideas DeWine has proposed throughout his campaign are promising. Congratulations to the governor-elect, and best of luck with your new job!

Since 2005, the Thomas B. Fordham Institute has published annual analyses of Ohio’s state report card data, focusing on district and charter schools in Ohio’s Big Eight urban areas: Akron, Canton, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, Toledo, and Youngstown.

For the 2017–18 school year, we provide an overview of Ohio’s assessment and report card framework along with an examination of key academic data from 2017–18 state exam results and other indicators of post-secondary readiness.

The diagnosis is stark:

Ohio's annual checkup reveals that roughly two in five Ohio students are meeting college and career ready goals, with even lower rates across its largest cities. Clearly, more treatment is needed if Ohio's students are going to leave high school poised for success in college or the workplace.

We urge you to download the report and dig into the data yourself.

Editor’s Note: As Ohioans await the start of the new governor’s term in January, and as state leaders look to build upon past education successes, we at the Fordham Institute are developing a set of policy proposals that we believe can lead to increased achievement and greater opportunities for Ohio students. This is the eighth in our series, under the umbrella of empowering Ohio’s families, and the first to be published following the election of Mike DeWine as Ohio’s next governor. You can access all of the entries in the series to date here.

Proposal: Remove the statutory provisions that confine startup brick-and-mortar charters to “challenged districts” (the Big Eight, Lucas County, and other low-performing districts). Currently, this policy allows charters to start up in just thirty-nine of Ohio’s 610 districts.

Background: Ohio has more than 300 public charter schools (a.k.a. “community schools”) that educate over 100,000 students. Though online (“virtual”) charters have received much attention of late—much of it deservedly critical—the vast majority of charters are traditional brick-and-mortar schools, almost all of which are located in the major cities and serve primarily disadvantaged children (see figure 3; charters are signified by orange dots). The last detailed evaluation of this sector shows that Ohio’s urban charters make positive impacts on student learning, especially among low-income, black pupils. Research in other cities, such as Boston and New York City, also finds that charters add months of student learning and help to narrow achievement gaps. Charters can also benefit middle-class families; in fact, suburban charters in Arizona dominate US News & World Report’s top ten “Best High Schools” in the nation. Despite charters’ success in serving students of all backgrounds, Ohio law continues to prohibit them from locating in most of the state’s communities. This leaves most families with public school alternatives that are primarily confined to online charters and interdistrict open enrollment. Through the federal Charter School Program, Ohio has millions in funding that could be used to kick-start successful new schools via planning and implementation grants.

Proposal rationale: Across the nation, charter schools offer families and students learning environments suited to their needs. Brick-and-mortar charters have been proven to work for Ohio’s most disadvantaged students, and in other states they also do a fine job of serving middle-class families seeking different educational approaches for their children. Removing the state’s geographic restrictions is a necessary first step that would permit new charter school formation in all regions of Ohio, including many areas with significant numbers of students in poverty.

Cost: No significant impact on the state budget.

Resources: The map of Ohio charter locations is taken from America’s Charter Deserts, a web page published by the Fordham institute in 2018. The most recent rigorous evaluation of Ohio’s charter sector is by the Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) in the 2014 report Charter School Performance in Ohio. For summaries of charter research nationally, see Patrick Denice’s report, Are Charter Schools Working? A Review of the Evidence, published by the Center on Reinventing Public Education (2014), and Brian Gill’s article “The Effect of Charter Schools on Students in Traditional Public Schools” in Education Next (2016). And for more on Arizona charters, see U.S. News’ “Best High Schools Rankings” and June Kronholz’s article “High Scores at BASIS Charter Schools” in Education Next (2014). Information on challenged districts is at the ODE web page “Challenged School Districts“; and for information about Ohio’s CSP grant, see the ODE web page “Charter School Program (CSP) Grant.”

Editor’s Note: As Ohioans await the start of the new governor’s term in January, and as state leaders look to build upon past education successes, we at the Fordham Institute are developing a set of policy proposals that we believe can lead to increased achievement and greater opportunities for Ohio students. This is the ninth in our series, under the umbrella of creating transparent and equitable funding systems, and the second to be published following the election of Mike DeWine as Ohio’s next governor. You can access all of the entries in the series to date here.

Proposal: Repeal the statutory provision that prescribes a pass-through method for paying schools of choice—public charter schools, independent STEM schools, and the bulk funding for private school scholarship programs. Instead, they should require ODE to pay schools of choice directly—apart from districts—out of the state Foundation Funding appropriation. However, a separate budget line item (subject to a line-item veto) should not be created to fund schools of choice.

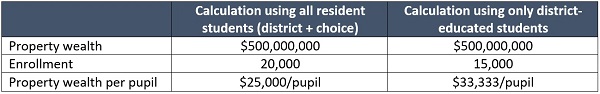

Background: The vast majority of state funds allocated to public charter schools, independent STEM schools, and private school choice programs are passed through local district budgets. Here’s how it works: the state (1) counts choice students in their resident districts’ headcounts for funding purposes; (2) subtracts funds designated for choice students from their districts’ state allocations; and (3) transfers dollars to students’ schools of choice. Although this method ensures that state money follows students to the schools they actually attend, it also creates problems. First, with deductions starkly displayed on districts’ state funding reports, the method perpetuates the falsehood that choice programs “take” money from districts and creates an adversarial and hostile relationship between districts and schools of choice. Second, this approach distorts districts’ funding formulae, as choice students are included in district per-pupil wealth calculations that determine their state aid. Consider the illustration below. Based on the number of students that the hypothetical district actually educates, its property wealth per pupil should be $33,333. But when all resident students—both district and choice pupils—are included in the denominator, that number changes to $25,000 per pupil, which would in turn generate higher levels of state funding.

Table: An illustration of how counting choice students affects districts’ funding formula

Proposal rationale: The circuitous pass-through method is a source of frustration for all public schools, adds unnecessary complexity to the funding system, and distorts districts’ state funding amounts. Direct funding of schools of choice would be clearer, fairer, more straightforward, and less contentious.

Cost: Modelling should be done to estimate the impact on the state budget. In isolation, the state may experience modest cost reductions by removing choice students from district funding formulas; however, such reductions would likely interact with the guarantee that today shields districts from losses in state aid. With the guarantee in place, the state may incur additional costs to transition to direct funding. Note, too, that to the extent that this transition results in extra funds, those dollars would remain with district schools rather than charters.

Resources: For discussion on pass-through and direct-funding methods, see A Formula That Works: Five Ways to Strengthen School Funding in Ohio, a report written by Bellwether Education Partners’ Jennifer Schiess and colleagues and published by the Fordham Institute (2017). For a brief overview of the charter/district funding system in Ohio, see the Fordham Institute video Ohio’s Method of Funding Charter Schools is Convoluted (2017). The ODE provides a detailed description of deductions in School Finance Payment Report (SFPR): Line by Line Explanation (2018).

Editor’s Note: As Ohioans await the start of the new governor’s term in January, and as state leaders look to build upon past education successes, we at the Fordham Institute are developing a set of policy proposals that we believe can lead to increased achievement and greater opportunities for Ohio students. This is the tenth in our series, under the umbrella of maintaining high expectations for all students. You can access all of the entries in the series to date here.

Proposal: The ODE should move state testing windows from April to May, and state law should require the ODE to pilot computer-adaptive testing.

Background: Ohio administers statewide math and English language arts (ELA) exams in grades 3–8; science exams in grades 5 and 8; and math, ELA, science, and U.S. history and government exams during high school. These exams provide parents with regular feedback on their children’s progress against academic standards. And because state assessments yield objective, comparable information on pupil achievement, they also form the basis of a school report card that offers an impartial, external check on district and school performance. Yet implementing such a battery of assessments brings its own challenges. Schools have raised concerns about the amount of time this testing takes, leading Ohio lawmakers to place a cap on state and district testing time and to eliminate state social-studies exams in grades 4 and 6. With testing windows that generally span the entire month of April, state exams can also disrupt instructional time. The springtime administration of tests also means that many weeks of school remain in May and June after the assessment cycle concludes. Also worrying is the long delay before schools and parents receive assessment results—sometimes after the next school year begins in the fall—greatly diminishing their value to those who depend on this information.

Proposal rationale: High-quality, statewide assessments are critical to a healthy school system, and Ohio needs to take steps to maximize their value and minimize their burdens. Moving the testing window to May—a strategy other states are pursuing—would allow more time for teachers to teach. Shifting Ohio from its present fixed-form exams, in which the questions are generally the same or similar for all students, to computer-adaptive exams has the potential to reduce testing time and accelerate the return of results. By adjusting the difficulty of the questions that a student is asked, computer-adaptive exams can pinpoint achievement with fewer questions. Recognizing such benefits, several states, including those in the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium, have moved to computer-adaptive testing. However, given the technical challenges associated with digital assessment, Ohio should pilot adaptive testing in a sample of schools before considering statewide use.

Cost: The state currently budgets about $50 million per year, or roughly $30 per student, for its assessment program. We estimate that an additional $10 million per year in state funding would ensure sufficient human and technical resources for an expedited testing and reporting schedule and to pilot computer-adaptive assessments. Additional expenditures may be required if Ohio decides to fully transition to computer-adaptive testing.

Resources: For more on states moving testing windows to later in the school year, see Kristen Graham’s 2017 article “PA Kids Will Take Fewer Tests, Given Later in the Year” in the Philadelphia Inquirer and Leslie Postal and Gray Rohrer’s 2017 article “Move Testing to the End of the School Year, Lawmakers Say” in the Orlando Sentinel. For information about computer-adaptive testing, see Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium’s “Testing Technology” and G. Gage Kingsbury and colleagues’ 2014 article “The Potential of Adaptive Assessment” in Educational Leadership. For information regarding state tests and testing windows, visit ODE’s web page “2017–2018 Testing Dates.”