In Ohio’s great graduation debate, we at Fordham have warned that lowering the bar is tantamount to the “soft bigotry of low expectations.” Weakened standards, such as those pushed by the State Board of Education, imply that many low-income pupils need alternative routes to diplomas because they’re unable of reaching the state’s academic or career-technical requirements. Yet as this piece discusses, lowering our sights won’t just hurt poor students, it’ll also ask much less of our young men, especially Ohio’s young men of color.

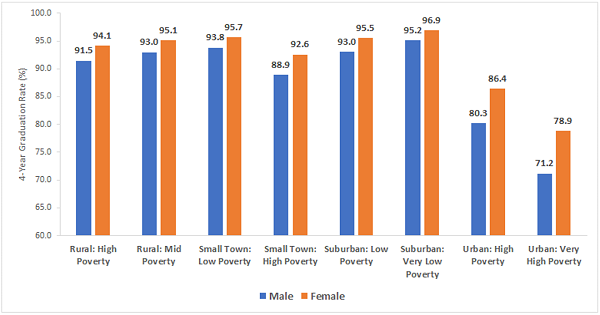

Consider the four-year graduation rates for the class of 2017, the most recent available, displayed in the figures below. This was the final cohort subject to Ohio’s “old” graduation requirements, which included passage of the low-level Ohio Graduation Tests (OGTs). Figure 1 shows average graduation rates across Ohio’s district typologies, classifications developed by ODE to group districts with similar socio-economic and geographic characteristics. You’ll notice that graduation rates for males trail behind their female counterparts across all typologies, suggesting that high-school completion for young men should be a widespread concern. The disparities are most visible in Ohio’s high-poverty urban areas that include big- and small-city districts, and some inner-ring suburbs.

Figure 1: Average four-year graduation rates across Ohio’s district typologies by gender, class of 2017

Note: In a number of districts, graduation rates are reported by ODE as “>95%”; in these cases, I impute 97.5 percent, the midpoint between 95 and 100 percent. Average graduation rates by typology are weighted by the number of students in each district’s graduating class. Graduation rates in Figure 1 and 2 do not include charter students.

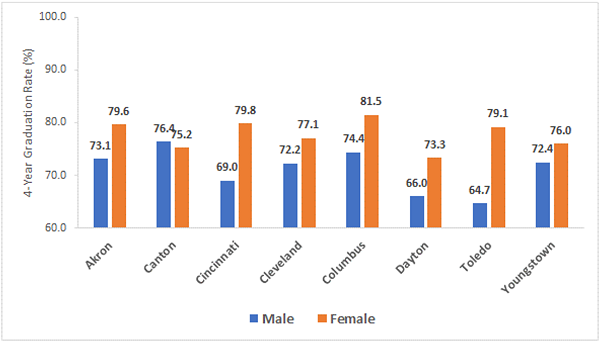

Figure 2 offers a closer look at graduation rates in Ohio’s big-city districts, known as the Big Eight. These districts comprise the “Urban: Very High Poverty” group in Figure 1 and educate a disproportionate number of low-income students and students of color. The chart below shows that, in seven of the Big Eight districts, male graduation rates fall behind. In Toledo, for instance, just 65 percent of young men graduate in four years, while 79 percent of young women do so—a 14 percentage point difference. In Cincinnati, the gap is 11 points; in Columbus, it’s 8; and in Dayton, it’s 7. The figure below also suggests that gender gaps within cities can’t be explained by poverty: Males from Toledo, for instance, likely come from similar economic backgrounds as girls—yet they graduate at much lower rates.

Figure 2: Four-year graduation rates across Big Eight districts by gender, class of 2017

The gender gap in graduation rates is troubling, but what can we make of it?

First, let’s applaud the achievements, depicted in these data, of Ohio’s young women. The decades-long push to strengthen girls’ educational opportunities has borne fruit, as they’ve motored past boys in not only high school graduation, but also college completion. As with efforts to narrow any type of achievement gap, including those displayed above, we shouldn’t lower the ceiling. Rather, the focus should be on efforts to raise the floor—in this case, improving the education of boys.

Second, we should consider the consequences of lower graduation rates for males. Lacking even high-school level competencies, low-skilled men are sure to face long odds of labor market success, likely resulting in menial jobs and bouts of unemployment. Such ramifications might spill over into other areas of their lives, including higher rates of divorce, depression, or incarceration.

Third, it’s worth thinking about why we see this gender gap. On one level, it simply reflects academic troubles. State exam results from the 2014–15, when the class of 2017 would’ve taken their OGTs, confirm that girls did better on reading and writing exams, though results in other subjects—math, science, and social studies—weren’t noticeably different. Of course, lower graduation rates also reflect higher dropout rates which may be tied to weaker non-academic competencies, such as self-discipline, that are needed to persist in high school.

One could ask more probing questions about why boys underperform. Non-schooling factors could certainly play a role: For instance, though still the subject of academic debate, it’s likely that boys are more adversely affected by family breakdown.

Yet schools themselves may be having a more difficult time educating boys. They are staffed primarily by women, even though research indicates that boys often achieve at higher levels when they have male instructors. There may be a cultural dimension as well in which scholastic achievement isn’t viewed as “masculine,” perhaps resulting in lower expectations for boys. As child psychologist Michael Thompson puts it: “Does being a good student make you a real man? I don't think so… It is not cool.”

It’s this last explanation that troubles me most in our debates over graduation requirements. Does championing low standards reinforce a repugnant idea that males, particularly young men of color, are unable to do well in school? Like overprotective parenting, does it shelter the young men who will be expected to lead as responsible heads of households? And will it leave many men without the knowledge and skills necessary to be reliable breadwinners?

In the short term, giving out diplomas will make everyone feel good by inflating graduation rates, including those of males. But this is the easy way out. It allows young men to bypass the hard work needed to prepare for life after high school, whether college, career, or the military. From the gridiron to the baseball diamond, we regularly challenge young men to work hard and do their best. Yet we expect so little of them in the classroom. Tragically, this way of thinking will only leave thousands more men behind.