The irrational hysteria over the billion-dollar price tag of Ohio’s private school scholarships

The uproar over private school scholarship programs, which support the education of more than 150,000 Ohio students, continues to drone on.

The uproar over private school scholarship programs, which support the education of more than 150,000 Ohio students, continues to drone on.

The uproar over private school scholarship programs, which support the education of more than 150,000 Ohio students, continues to drone on. Critics’ rhetoric can get intense, including labelling these school choice programs an “existential threat” to public education and demeaning them as a “vouchers scheme.” In recent months, detractors have eagerly cited the expense of providing scholarships—about $1 billion per year—likely an effort to smear the programs as bloated and little more than government waste. Skeptical media outlets have also routinely featured the amount in headlines.

A billion dollars is certainly a serious chunk of change. But when considering who these funds support, as well as the amount public schools receive (spoiler alert, it’s $30 billion), scholarship expenditures, at 3 percent of Ohio’s K–12 funding, are not quite as alarming as critics maintain.

Let us first remember that these funds—it’s true!—are being used to educate students. Dollars aren’t just being “given” willy-nilly to private schools, as one op-ed headline once framed it. Schools only receive scholarship funds when parents choose them for their sons and daughters. But who is benefitting from these programs, and how much is being spent on their education? And are the dollars simply going to wealthy folks, as recent news stories have suggested?

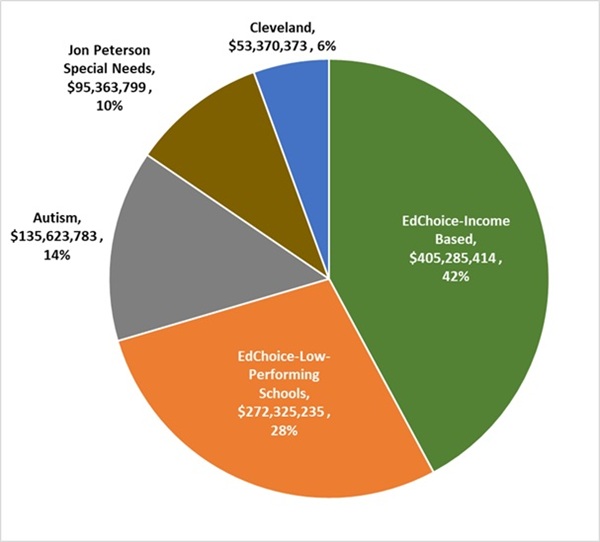

The figure below shows the breakdown of funding across all five of the state’s scholarship programs in FY24. We see that a total of $962 million was spent on these initiatives—a sum that is usually rounded to the more outrage-inducing amount of $1 billion.

Figure 1: Scholarship spending across all programs, FY24

A closer look at scholarship spending should calm fears that these dollars are being used in wasteful or inappropriate ways.

In sum, a more careful analysis shows that the vast majority of the $1 billion are being used to support students with disabilities, students who would otherwise attend low-performing public schools, and children from low- and middle-income households. What’s wrong with that? Some continue to argue that taxpayer dollars shouldn’t go to religious schools, but that borders on intolerance to parents who seek an education for their children that aligns with their beliefs. It also ignores the fact that scholarship-receiving families pay their fair share of state and local taxes, too, including taxes that support public schools their children do not attend.

Speaking of public school funding, let us also be mindful that the scholarship expense pales in comparison to their revenues—important context that is almost never mentioned. Instead, critics routinely contend that the $1 billion—and presumably, the 150,000 scholarship students with it—should be rerouted to “underfunded” public schools. As one commentator put it:

Ohio Republicans care about diverting a ton of taxpayer money (desperately needed by cash-strapped, levy-dependent districts) to benefit private school families, regardless of income or need, who choose to send their darlings to diocesan grade schools and religious high schools.

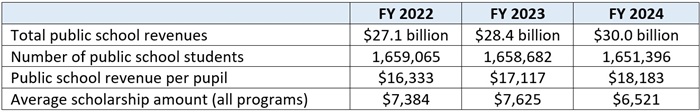

Notwithstanding the cringy name calling of children, the writer is wrong to portray traditional districts as “desperately…cash-strapped.” In FY24, public schools received $30 billion—thirty times more funding than what’s spent on private school scholarships. Of course, public schools enroll more students, but not anywhere near thirty times more students (it’s about ten times). Hence, on a per-pupil basis, public school funding is 2.8 times the average scholarship amount across all five programs ($18,183 versus $6,521). As the table below indicates, this is no one-year blip: Public school funding also greatly exceeded scholarship funding in FY22 and FY23, as well.

Table 1: Public school funding versus scholarship amounts

* * *

Sky-is-falling rhetoric is par for the course when it comes to private school scholarship programs. But the hysteria rarely matches reality. As for the $1 billion being spent on scholarship programs, the truth is that the vast majority of these funds support less advantaged families who rely on scholarships to enroll their child in a private school of their choice. Meanwhile, scholarship spending remains small in comparison to overall public school funding. As Ohio continues to debate school choice programs, here’s hoping for a calmer, more fact-driven discussion.

Tackling Ohio’s teacher vacancy data problem should be a priority for lawmakers in the upcoming year. Prior to the holidays, I analyzed how a few important tweaks to the provisions of last session’s House Bill 563 could provide state leaders with an opportunity to do so. But data collection and transparency weren’t the only focus of the bill. It also proposed some innovative ways to support student teachers that could help bolster recruitment efforts.

It might seem odd to focus on student teaching as a recruitment strategy. After all, most teacher candidates are three years into their education degrees by the time they begin student teaching. But unlike apprentices, who are paid during on-the-job training, student teachers work full time for free. Not only that, many are required to continue paying college tuition. Candidates must cover fees for required background checks and licensure tests out of their own pocket. And to top it all off, most preparation programs encourage candidates not to work second jobs. That means prospective teachers must somehow afford housing, food, transportation, and other living expenses without any income whatsoever. For college students or career changers who are on the fence about education, that’s a heck of a financial deterrent. And for students who manage to make it work by relying on student loans, the cost is merely deferred—with interest, and while working in a field that pays less than others. Even if they’re eligible for federal student loan forgiveness programs, teachers won’t escape paying at least some of that debt.

If policymakers want education to be a more attractive career option, then student teaching must become less of a financial drain. HB 563 might have died at the end of the 2024 legislative session, but the ideas it put forward can and should be resurrected in 2025. Let’s examine three.

1. Stipends

The simplest way to erase the financial strain of student teaching is to pay teacher candidates for their work. One way to do so is for the state to provide stipends to students who are enrolled in teacher preparation programs while they work as student teachers. This would require the legislature to set aside funding. And since the state’s coffers aren’t quite as flush as in years past, including a new stipend program in the upcoming state budget could give some legislators pause. But teacher shortages have been a persistent problem for years. Ensuring that prospective teachers aren’t enduring financial hardship while completing mandatory student teaching requirements is a relatively simple policy fix that could boost recruitment efforts. Lawmakers could also initially require that stipends be means-tested, so that limited state funds would be directed to the most disadvantaged college students.

Student teacher stipends would also help Ohio remain competitive with nearby states. In 2023, Pennsylvania lawmakers passed Act 33, which established a $10 million Educator Pipeline Support Grant Program that provides up to $15,000 to eligible student teachers. Since then, Pennsylvania leaders have allocated a total of $30 million to the stipend program. Michigan, meanwhile, provides its student teachers with stipends of $9,600. If neighboring states are making teacher training more affordable, then it stands to reason that prospective teachers might choose to go out of state for college and, eventually, work. That’s the last thing Ohio leaders want, especially since they’ve already invested in efforts to keep talent in Ohio.

2. Licensure test fee waivers and reimbursements

In Ohio, teacher candidates must pass exams that assess their pedagogical and content knowledge prior to earning a teaching license. Required exams vary based on the subject and grade level that candidates plan to teach, but typically cost over $100 each.[1] For a prospective first grade teacher, these fees add up to more than $350. For a future high school math teacher, the total is above $200. Candidates who don’t pass the first time must pay to take the test again. Add in the cost of background checks while taking into account that student teachers work for free, and it’s no surprise that many candidates struggle to cover test fees. To help ease the financial burden, DEW could provide test fee waivers/reimbursements based on financial need to teacher candidates while they are student teaching. Given that the state already offers fee waivers for the ACT and SAT, it makes sense to extend this aid to prospective teachers.

3. Tuition waivers

Despite working full time in schools, many student teachers are still required to pay college tuition. This is a financial double whammy. Not only are they potentially accumulating additional student debt, they’re doing so while working full-time for free. To ease the financial strain, lawmakers could require higher education institutions to waive tuition for teacher candidates while they complete student teaching. As with stipends, lawmakers could begin with means-tested waivers. But going forward, it’s probably in the state’s best interest to ensure that all of its future teachers are shielded from a financial double whammy that could send them searching for a new career.

***

Student teachers don’t typically come up when policymakers and advocates discuss retention and recruitment efforts. But they should. These individuals are on their final lap before they head into the classroom, and the best way to ensure they cross the finish line is to prevent mandatory student teaching experiences from draining their bank accounts. Making student teaching a more financially feasible requirement could also boost the recruitment of new teachers, especially those from low-income backgrounds and career changers who can’t afford to forego income while training. Last year’s HB 563 offered several simple and relatively inexpensive policy fixes that could address these issues. Here’s hoping lawmakers include those provisions in the upcoming state budget.

[1] Although most exams cost $109, Ohio’s Foundations of Reading exam is more expensive at $139.

Since Ohio’s first public charter schools launched in the late 1990s, we at Fordham have documented large funding disparities between charters and traditional school districts. Systemic underfunding is horribly unfair to the charter school students who receive less for their education than their district-attending counterparts just because of their choice in public school. The gaps have also disadvantaged charters in the competition for teacher talent, and have limited their ability to provide extra student supports and their capacity to expand.

This gloomy picture has begun to change in recent years thanks to the leadership of Governor DeWine and Lt. Governor Husted. In 2019, they proposed, and shepherded through the legislature, a new funding initiative that provides supplemental aid to high-performing charter schools—generally, those that post higher test scores than their local district and demonstrate strong academic growth for their students .

In the first four years of the program (FYs 2020–23), qualifying schools received roughly $1,000 to $1,500 per pupil in additional support, depending on the year. While these dollars did not erase the funding gap, they put a sizeable dent in it. More importantly, the extra resources made a difference for schools and students. According to a rigorous analysis by Ohio State University’s Stéphane Lavertu, the dollars allowed charters to raise educator pay and retain more teachers, which helped in turn to lift student achievement.

The last state budget took additional measures to narrow charter funding gaps even further. The headliner was a big increase in the high-quality funding. In FY24—the first year of the enhanced program—sixty-five charters, or about one in five statewide, received an average supplement worth $2,898 per pupil,[1] more than double the prior year amount. But that’s not all. Understanding that charter students writ large deserve fairer funding, legislators also created a new charter equity supplement. This funding stream provides $650 per pupil to all brick-and-mortar charters regardless of qualification for the high-quality dollars. While nowhere near the high-quality amounts, this has been another important step forward in the push for charter funding equity.[2]

These are all praiseworthy policy advances, but where exactly does this leave Ohio charter schools in terms of funding parity vis-à-vis local districts?

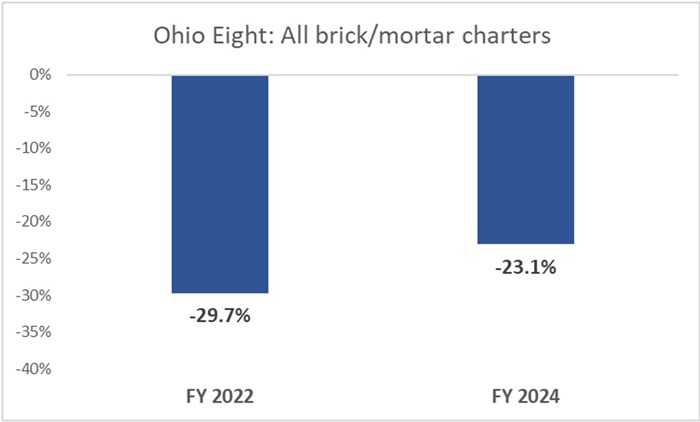

Figure 1 shows the results for the Ohio Eight, the cities where the vast majority of brick-and-mortar charters are located (Akron, Canton, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, Toledo, and Youngstown). The average charter school in these locales still faced a sizeable funding gap in FY24, receiving 23 percent less than their local district. But this shortfall does represent significant progress compared to the 30 percent gap prior to the enhancements passed in the last budget. Worth noting is that the overall charter funding disparity would have narrowed further had the same number of Ohio Eight charters qualified for the high-quality funding in FY24 as did in FY22.[3] If that number had remained constant, FY24 gap would have fallen closer to 20 percent.

Figure 1: Average funding shortfall relative to local districts, Ohio Eight brick-and-mortar charters

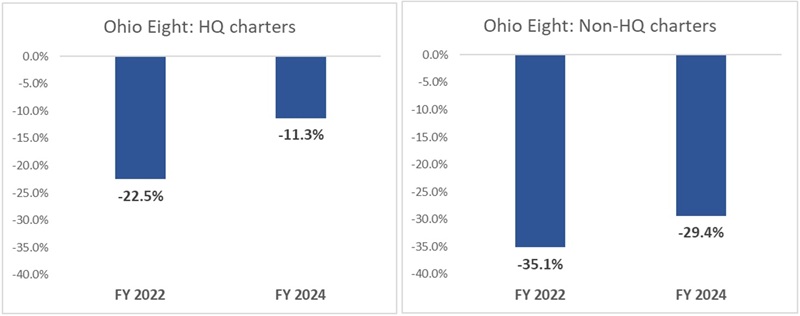

The overall average, however, masks the more impressive progress among high-quality charters. Reflecting the substantial funding increase for high-quality charters starting in FY24, the figure below shows that the average gap for these schools narrowed from 23 to 11 percent between FY22 and FY24—impressive, but not quite full funding equity. In contrast, schools falling short of the state’s high-quality criteria continued to face severe shortfalls. While making up some ground through the brand-new equity supplement, their funding still falls 29 percent below that of local districts.

Figure 2: Average funding shortfall relative to local districts, Ohio Eight charters by high-quality (HQ) status

* * *

Ohio’s push to improve charter funding has focused heavily on high-quality schools. Instead of receiving approximately 70 cents on the dollar compared to local districts, these charters now receive about 90 cents. That’s real progress toward funding parity, and policymakers should wholeheartedly continue their support of quality charters. At the same time, they should also recognize the continuing need to support all charter students, including those attending schools that miss the state’s quality criteria. Many of these students are low-income, students with disabilities, or—in the case of dropout-recovery charters—adolescents who have fallen behind in their education. Boosting their funding levels through an increase in the charter equity supplement would give these schools more of the resources they need to effectively serve students.

This year’s biennial budget bill presents yet another opportunity to create a funding system that treats all Ohio students fairly, no matter their choice of school. As lawmakers begin to wade deep into the budget, they shouldn’t forget the 85,000 students who attend one of Ohio’s brick-and-mortar charter schools.

[1] The budget bill provides qualifying schools with up to $3,000 per economically disadvantaged pupil and $2,250 per non-disadvantaged pupil.

[2] The last budget also doubled brick-and-mortar charters’ per-pupil facilities aid to $1,000 per pupil. This narrows longstanding facility-related funding gaps, an issue that is separate from the day-to-day “operational” funding gap—the focus of this analysis.

[3] The number of Ohio Eight schools qualifying for high-quality funding declined from 82 to 53 from FY22 to FY24.

First-year teachers—especially those who begin on the lower end of the performance scale—tend to improve over time if they remain on the job, according to rigorous research studies. These findings are the same whether the analyses use student test scores or rubric-based classroom observation scores. But little is yet known about what exactly drives their improvement. A new study using data from Tennessee aims to shed some light, combining both types of scoring.

Beginning in 2011–12, Tennessee implemented a new evaluation system that required rubric-based classroom observations for all teachers every year, conducted by a principal or assistant principal. The number of annual observations range from 1 to 4, with newer teachers typically evaluated more often than their veteran peers. Grade level, subject matter, and prior evaluation results also play a part in the number of observations. Teachers are rated from 1 to 5 on each of nineteen rubric items, and evaluators also select one item as an “area of refinement” (AOR) for the teacher. For this study, analysts focused on AORs as a ripe area of comparison to observe teacher performance changes over time.

The choice of AOR is up to each evaluator, but the state offers these guidelines: (a) Which areas on the rubric received the lowest scores? (b) Which of these areas would have the greatest impact on student achievement or other areas of the observation rubric? (c) In which area will the teacher have the most potential for growth? School leaders are then supposed to help the teacher improve in whatever area is chosen.

The research team looked at results from 650,000 classroom observations (including those for about 17,000 novice teachers) conducted from 2012–13 through 2018–19, comprising all rated rubric items and all AOR selections. Students’ value-added scores for teachers over this time period are also analyzed. Empirically, they found that novice teachers and veterans show sizeable differences in which rubric items are chosen by raters as the AOR, with novices substantially more likely to receive an AOR relating to classroom management and the presentation of instructional content—basic teaching skills—whereas veterans are more likely to receive an AOR relating to higher-order aspects of the job, such as activities that teach students problem-solving skills. The lowest-performing novice teachers (based on value-added scores) were also more likely to receive these basic-skill AORs than their high-performing peers. Higher-performing novices and veterans are remarkably similar across most rubric item scores and chosen AORs.

To determine whether identification of an AOR leads to improved practice, the researchers constructed a balanced panel of teachers for whom they could observe the first five years on the job. They mainly focused on the two skills—presenting instructional content and managing student behavior—that showed the biggest novice-veteran gaps. They observe that the lowest-performing quartile of novices become relatively more effective in these areas, judging both from rubric scores and by the decreasing probability that these items are chosen again as the AOR as the novices gain experience. Additionally, there are increases in the probability that higher-order skills will begin to be chosen as the AOR for these teachers over time. However, novices who were higher performing at the outset show far less improvement over their first five years, indicating that they have likely already mastered the basics but still require time to start building the higher-order skills that showed up as their AORs.

In discussion, the researchers assert that their findings show improvement in overall effectiveness of novice teachers in the first few years on the job, driven specifically by improvements in core teaching skills among the lowest initial performers. Evaluators are seeing and noting these basic skills as needing refinement and are likely, as the Tennessee evaluation system expects, working with the novices to improve these specific practices. While the same process is happening with higher-performing novices, the skills they need to improve appear less likely to rise in the first five years, despite whatever assistance is being provided to them.

Overall, these are promising findings, as they provide a tentative roadmap for how school leaders and policymakers can best support new teachers. However, this analysis includes only individuals who stayed in the classroom for at least five years; nearly half of new teachers head for the exits before then. That could lead to some biasing of results. For example, it’s possible that low-performing teachers who showed little or no improvement were nudged out the door—or exited on their own—and thus did not get included in the study. Additionally, we have no data on what specific supports or development efforts school leaders provided in response to any AOR selections, which somewhat blunts the wider applications of these findings.

SOURCE: Brendan Bartanen, Courtney Bell, Jessalynn James, and James Wyckoff, “‘Refining’ Our Understanding of Early Career Teacher Skill Development: Evidence From Classroom Observations,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis (January 2025).

The Advanced Placement (AP) program, celebrating its seventieth anniversary this year, has largely lived up to the promise of encouraging and rewarding ambitious high school students looking to prepare themselves for college rigor. Students who participate in AP courses generally have better chances to attend and succeed in college compared with students who do not. But questions persist about a lack of access for various underrepresented groups, leading to measurable gaps in participation and achievement over the years. The College Board, which runs the program, has urged policymakers across the country to take action to increase resources, access, and opportunity. A new report looks at one state’s efforts to do just that.

Arkansas mandated universal AP access starting in 2003, and strengthened that effort in 2005 by covering AP exam costs for all students. The mandate requires that every school provide at least one AP course in each of the core areas of math, science, English, and social studies. Theoretically, the mandate removed the most commonly-reported barriers to participation among students nationwide: availability and affordability. A group of researchers led by Andy Parra-Martinez from Mississippi State University dug into the data to examine the impacts of these policies on participation and, to a lesser extent, on student outcomes.

The research team utilized data from the Arkansas Department of Education covering the period 2016 to 2021, expanding on previous research that ended in 2015. The anonymized data include student demographic characteristics such as gender, race, gifted and talented status, English language learner status, special education status, and family income (as determined by participation in the subsidized lunch program). Additionally, they have access to students’ achievement in English language arts, math, and science subtests prior to high school. They use multilevel modeling to investigate the relationship between student- and school-based factors that influence AP enrollment and course success.

Approximately 31 percent of Arkansas high school students enrolled in at least one AP course over the time period studied here. This is an increase over both the pre-mandate (just 4 percent) and the 2015 (19 percent) figures, and approaches the national average of 33 percent. A majority of AP enrollees in Arkansas took one or two courses over their high school career. Female students were 1.6 times more likely to participate than males; Asian students and Hispanic students were more likely to participate than White students (1.8 times and 1.4 times, respectively); and students identified as gifted were 1.4 times more likely more likely to participate than their non-identified peers. AP participants also had higher academic achievement prior to high school than non-participants. Low-income students, English language learners, and special education students were least likely to enroll in an AP class.

More than 90 percent of AP enrollees ultimately earned course credit, with no significant differences in attainment based on any demographic characteristic. This is consistent with AP course outcomes previously in Arkansas and nationally. Importantly, though, Parra-Martinez and his team did not have access to data on which students took official AP exams over the study period, nor how the test takers did on the College Board’s score scale from 1 to 5. As a result, the researchers suggest that the use of school/teacher assessments, rather than official AP examinations, might be inflating grades and awarding course credits erroneously. Separate data from College Board, cited in the report, show that 22 percent of Arkansas students in grades 10–12 took at least one AP exam in 2022, an increase of 2 percent from 2012. Mean scores for Asian American students in the state grew from 2.6 to 3.0 and for White students from 2.2 to 2.5 over that same period. Gains for Hispanic students (from 2.0 to 2.2) and Black students (from 1.5 to 1.7) were more modest.

Ultimately, universal access to AP courses boosted student participation overall and among many typically-underrepresented groups in Arkansas. However, low-income students and students with special needs were still less likely to participate than their peers. In fact, school-level analyses indicated that having higher proportions of these students in a building tended to depress AP participation among other student subgroups, as well. Additionally, outside data indicate that making the exams free for students did not significantly increase AP test taking or scores in Arkansas. The researchers suggest that true universality must consist of more than just widely offered courses. For example, they propose active recruiting of students by teachers or counselors and allocating school staff to specifically support students from groups who typically don’t participate or underperform. These efforts would surely result in higher participation numbers. But until we have a study that takes into account AP exam results, we can’t be sure that expansion efforts are leading to better outcomes for students.

SOURCE: Andy Parra-Martinez et al., “Does Policy Translate into Equity? The Association between Universal Advanced Placement Access, Student Enrollment, and Outcomes,” Journal of Advanced Academics (December 2024).