Diplomas Count 2012

Three out of four (73.5 percent) of the national 2009 graduating class successfully graduated high school in four years.

Three out of four (73.5 percent) of the national 2009 graduating class successfully graduated high school in four years.

Education Week and the Editorial Projects in Education (EPE) Research Center has released its 2012 graduate rate calculation and analysis. The researchers find three out of four (73.5 percent) of the national 2009 graduating class successfully graduated high school in four years. This is a 1.7 percentage point increase from 2008. The 2009 graduation rate represents the highest graduation rate since the late 1970s. When the author’s partition the data by race, they find that increasing Latino graduation rates, in particular, have contributed the most to the national improvement in the graduation rate.

How did the Buckeye State do? Education Week and EPE report that in Ohio 76 percent of its 2009 class graduated high school on-time. This rate places Ohio three percentage points above the national average and toward the middle of the pack—17th out of 51 states, including Washington D.C. The researchers also compare Ohio’s 1999 graduation rate with its 2009 graduation rate and they report that the rate has increased by seven percentage points, which again tracks closely with the national ten-year graduation rate increase of seven percentage points.

The report here adds to the conversation about how well the U.S. and each state are doing in graduating students. However, any calculation of the graduation rate should be taken with a grain of salt, for considerable debate and ambiguity still exists about how to calculate the graduate rate accurately. (See Fordham’s “The Great Graduation-Rate Debate” for an excellent analysis.) For example, the method used by the researchers here, called the Cumulative Promotion Index (CPI), finds—as already mentioned—that Ohio’s 2009 graduation rate stands at 76 percent. Meanwhile the Ohio Department of Education, using a different method, reports a 2009 statewide graduation rate of 83 percent. And starting this school year, the Ohio Department of Education will report and utilize for accountability yet another method of calculating the graduation rate.

Diplomas Count 2012

Education Week and the Editorial Projects in Education (EPE) Research Center

May 2012

It’s essential that great policies are not just created but also effectively articulated to those who must execute them. Policy implementation means putting theory into practice, wherein many logistic and technical complications can arise. This has happened in the case of teacher evaluation and accountability policies. Addressing these implementation issues is critical to education reform; as a result, the education reform organizations ConnCAN, 50Can, and Public Impact address questions and obstacles that arise in teacher evaluation in their May 2012 report, “Measuring Teacher Effectiveness: A Look ‘Under the Hood’ of Teacher Evaluation in 10 Sites”.

While many school districts have stuck with the same ambiguous methods of teacher evaluations, the report examines ten sites that include states, school districts, a charter school network, and a graduate school program (Delaware; Rhode Island; Tennessee; Hillsborough County, FL; Houston, TX; New Haven, CT; Pittsburgh, PA; Washington, DC; Achievement First; and the Relay Graduate School of Education in New York City). These institutions are all trying more rigorous, comprehensive approach to teacher evaluations; therefore, the report specifically focuses on their evaluation practices.

The authors consider the ways to measure student achievement and the value of nonacademic measures, like student perception and personal growth. For example, applying value-added measures for only math and science creates a problem for evaluating non-math and science teachers. Delaware is making use of multiple measures: state-defined metrics, approved internal school metrics, and growth goal measures. This combination of measures can compensate one assessment’s strength with another’s weakness. Achievement First, a charter network of twenty schools, uses lower weights for test performance in ungraded subjects, but includes student character development and quality instruction input in its evaluations. These are only a few strategies being used, in what the authors suggest are not perfect systems, but ones that show the way forward.

Readers probably won’t find an end-all be-all solution to teacher evaluation in this report. What you will find is a starting place—to brainstorm which methods best fit your objectives. We can learn a lot from these innovators. After all, an abstract idea isn’t much to the world, but when it is put into action it has potential, and that’s a start.

Measuring Teacher Effectiveness: A Look “Under the Hood” of Teacher Evaluation in 10 Sites

By Daniela Doyle and Jiye Grace Han

ConnCAN, 50Can, and Public Impact

March 2012

In this report, the Friedman Foundation for Education Choice looks at new models for schools. Using the term “greenfield,” from Rick Hess’ vision of areas where there are unobstructed, wide-open opportunities to invent and build, greenfield schooling strips down ideas of the traditional schoolhouse and gives schools the freedom to grow by tailoring education to a wider variety of students.

The report challenges the choice system as it currently stands, saying that existing school choice programs, while delivering slightly better outcomes, are not challenging the public school sector as they need to be. Greg Foster, who co-authored the report, begins by stating, “We know from previous research that vouchers (and equivalent programs like tax credits and ESAs) consistently deliver better academic performance, but the size of the impact is not revolutionary.”

Greenfield schools, the report states, would aid in a move to universal choice, a prerequisite for schools to innovate and grow and to prevent the shuffling of children from public to private schools. Universal choice would open opportunities to children of all ethnicities and income levels, many of whom have been excluded from private schools because of cost. Universal choice aims to lower tuition, and allow private schools to expand and serve new populations, which would afford educational entrepreneurs with dramatically more freedom and support than they currently enjoy even in charter schools. According to Foster, in communities where wider choice has been introduced, academic performance has improved.

While Ohio has several voucher programs, Foster believes the state’s families could benefit from universal choice due to the makeup of the private school sector in the state.

The Greenfield School Revolution and School Choice

By Greg Foster and James L. Woodworth

The Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice

June 2012

The Center for Reinventing Public Education (CRPE) takes a look at how strong charter management organizations manage staff to maximize the instructional and cultural coherence of the school.

The report uses data collected from a study of charter management organizations (CMOs) by Mathematica Policy Research and CRPE. The data includes interviews with nearly 150 teachers and leaders in 10 CMOs along with survey information from 37 central offices and more than 220 principals. The authors examined CMOs which had practical control (they could remove principals), were brick-and-mortar schools serving general student populations, and operated at least four or more charters.

Generally, the study found CMOs managed their teacher talent to impact cultural coherence using three levers.

First, they recruited and hired for fit. This can include targeting pipelines such as Teach For America and other teacher programs or schools that match their own school’s work culture and ideals. One hiring strategy is to communicate clearly what the school values most to its prospective candidates; another is to require applicants to submit sample lesson plans or to teach demonstration lessons (to gauge how they interact with students). Some CMOs involved other school community members, such as students and parents, to discern soft skills.

Second, they used intensive and ongoing socialization. Teachers reported they received feedback from both formal and informal observations given by their principal and peers. Not only did they cover instructional methods along with responding to behaviors, but the evaluations were expected to result in improving what is going on in the class room and ultimately helping students be successful. Real time feedback is given as a way to support teachers in executing the schools vision and to hold them accountable.

Third, they align pay and advancement to organizational goals. Teachers who excelled could be offered work in coaching and development as a way of supporting organizational goals and improving teacher practice. Monetary incentives were provided in the schools surveyed for taking on extra duties along with individual and school performance bonuses. Interestingly enough, the leaders’ professional opinion mattered more than assessments or performance metrics, when rewards were used.

The report draws a number of conclusions that can benefit the approach other charter and traditional districts take in using a more integrated approach to recruiting and keeping talent. By creating a cohesive process for recruitment, evaluation, and rewards, these schools have built an environment where teachers clearly know the expectations and what they can do to impact the school’s instructional and cultural coherence. District leaders can learn from the way CMOs manage talent if they are able to give the freedoms and supports along with the process.

Managing Talent for School Coherence

Center on Reinventing Public Education

Michael DeArmond, Betheny Gross, Melissa Bowen, Allison Demerritt, and Robin Lake

May 2012

Columbus City Schools are on the path to putting a property-tax levy on the November ballot (though it’s not a done deal; a citizen’s advisory committee will make its recommendation regarding a levy to district leaders next week and an official decision will follow). District officials say they need $355 million to maintain current programs, and to fund new initiatives, through the 2016-17 school year. Superintendent Gene Harris has indicated that the increase is needed, in part, because the district’s students are increasingly challenged – more kids are living in poverty, learning English, and disabled than in the past. Kids are also moving more frequently within, and to and from, the district.

Aside from a few big-ticket items (like sharing local tax dollars via grants with high-performing charter schools, increasing reading intervention in fourth and fifth grades, and purchasing new school buses), the district hasn’t detailed if, and how, it might alter its overall spending patterns if the levy passes. In the meantime, we can look at how the district is spending money today versus a few years back, for clues.

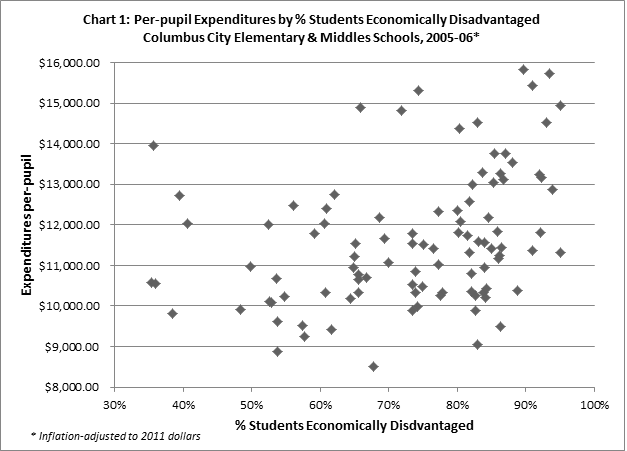

Charts 1 and 2 show per-pupil spending for Columbus’s elementary and middle schools against the percent of students in each school who were economically disadvantaged for the 2005-06 and 2010-11 – the most recent year for which data are available—school years (2005-06 dollars are adjusted for inflation to reflect 2011 values).[1]

Source: Ohio Department of Education PowerUsers reports

What do the charts tell us?

Demographics: Students are more economically disadvantaged in 2011 than they were in 2006.

Spending: Spending has increased slightly, but it isn’t clear that increases are focused on students who need it most.

There is also no clear relationship between school performance and spending. In 2011, the top-achieving Columbus elementary or middle school, Clinton Elementary, spent $13,928 per student – about $2,000 more than the lowest-achieving school, Fairwood Alternative Elementary, spent $11,560. Yet spending across the district doesn’t mirror such a pattern. Other high performers spend less, or only slightly more, than Fairwood; and low-performers are spending more than their high-performing peers. Similarly, there is no apparent relationship between spending and the percent of students who are English language learners, have special needs, or are highly mobile.

Alex Fischer, CEO of the Columbus Partnership and a member of the levy advisory committee, encourages the district to seek “transformational change” as part of its levy request. Moving toward a system where per-pupil spending is based on students’ educational challenges and follows kids to the school they attend would certainly be such a change. Columbus’s students are more disadvantaged than they were five, or ten, years ago. The district acknowledges this reality and that more money may need to be directed to students who need it most. Current spending patterns show that the district isn’t systematically directing more dollars toward neediest students today, but such a shift – to a student-based funding model (aka weighted-student funding) – could be made, and should be considered, along with passage of a levy.

[1] Schools that serve a very high population of special needs students and the district’s “welcome centers” – which serve as a transition program to help newly arrived immigrant students build basic English and academic skills – have been removed from this analysis.

The Fordham Foundation has authorized (aka sponsored) charter schools in Ohio since 2005 and currently oversees eight schools (three more will join our portfolio this fall). As the 2011-12 school year ends, we want to highlight the unique events and successes that happened in our schools this year.

Columbus Collegiate Academy (CCA)

Last summer, CCA moved from space that it shared with a Weinland Park area church since the school opened in 2008 to a new location on Main Street, in the near eastside of Columbus. In terms of student achievement, 40 students were “NWEA all-stars” – meeting ambitious academic growth targets set for them in both reading and math. Sixth graders also participated in “Run the City,” a day-long project where they dealt with the ins and outs of running a city, including banking, marketing, and advertising. Students also got a glimpse of college life with full-day visits to the Ohio State University, Ohio Dominican University, Ohio Wesleyan University, and Denison University. CCA leadership recently launched a new charter management organization, the United Schools Network, which will open a second middle school, Columbus Collegiate Academy-West, this August.

KIPP: Journey Academy

KIPP received excellent news this spring when the school was awarded the prestigious New Leaders for New Schools EPIC Award for outstanding academic growth. KIPP: Journey Academy was the only school in Ohio and the only KIPP school nationwide to receive the award. The inaugural class of “KIPPsters” graduated from the middle school this year and will take their next step on the journey to college as they matriculate to some of the highest performing high schools in Columbus. KIPPsters also extended their learning beyond the classroom and participated in end-of-year trips to Washington, D.C.; West Virginia; Chicago; and Atlanta.

Dayton Leadership Academies: Dayton Liberty Campus and Dayton View Campus

Dayton Liberty and Dayton View Academies are excited about an influx of new staff for the coming school year: this spring the schools received confirmation that over the next two years at least ten Teach For America corps members will be placed across the two campuses. Teach For America was officially introduced to the Southwest region of Ohio earlier this month. Both Teach For America and the Dayton Leadership Academies are excited about this new partnership and the impact it could have on student achievement.

Phoenix Community Learning Center

The Phoenix Community Learning Center, in Cincinnati, capped off 2012 with its signature event, Culturama. Culturama is a three-day school-wide event during which classrooms explore particular aspects of a theme country’s culture, food, music, literature, industry, and more. This year, the Caribbean nations were the focus, as captured by a group of eighth-grade students who decorated this door.

Springfield Academy of Excellence

In 2011-12 the Springfield Academy of Excellence added the Project MORE reading intervention program. Project MORE utilizes volunteers to provide one-on-one mentoring to students reading below grade level. This year the program served 16 students and the school reports that it had a positive impact students’ progress between reading levels.

Sciotoville Community School (aka East High School)

This spring, two Sciotoville students presented at the State High Schools that Work Best Practices Showcase. Student Christopher Rittner won the High Schools that Work Senior Achievement Award. He also won the Honda Math Medal Award. In sports, the Tartan’s softball team broke the school's record for the most softball wins in the school history, finishing the season at 22-5. Several students also placed in the 2011-12 Scioto County Art Show.

Sciotoville Elementary Academy

Junior High Language Arts teacher, Kristen Wawro took two student teams to the district Power of the Pen Interscholastic Competition for Young Writers. One seventh grader and five eighth graders qualified for the regional tournament, and one eighth grader went on to qualify for the state competition. And of course both Sciotoville schools were featured in our short documentary, The Tartans: The Story of the Sciotoville Community Schools.

Education Week and the Editorial Projects in Education (EPE) Research Center has released its 2012 graduate rate calculation and analysis. The researchers find three out of four (73.5 percent) of the national 2009 graduating class successfully graduated high school in four years. This is a 1.7 percentage point increase from 2008. The 2009 graduation rate represents the highest graduation rate since the late 1970s. When the author’s partition the data by race, they find that increasing Latino graduation rates, in particular, have contributed the most to the national improvement in the graduation rate.

How did the Buckeye State do? Education Week and EPE report that in Ohio 76 percent of its 2009 class graduated high school on-time. This rate places Ohio three percentage points above the national average and toward the middle of the pack—17th out of 51 states, including Washington D.C. The researchers also compare Ohio’s 1999 graduation rate with its 2009 graduation rate and they report that the rate has increased by seven percentage points, which again tracks closely with the national ten-year graduation rate increase of seven percentage points.

The report here adds to the conversation about how well the U.S. and each state are doing in graduating students. However, any calculation of the graduation rate should be taken with a grain of salt, for considerable debate and ambiguity still exists about how to calculate the graduate rate accurately. (See Fordham’s “The Great Graduation-Rate Debate” for an excellent analysis.) For example, the method used by the researchers here, called the Cumulative Promotion Index (CPI), finds—as already mentioned—that Ohio’s 2009 graduation rate stands at 76 percent. Meanwhile the Ohio Department of Education, using a different method, reports a 2009 statewide graduation rate of 83 percent. And starting this school year, the Ohio Department of Education will report and utilize for accountability yet another method of calculating the graduation rate.

Diplomas Count 2012

Education Week and the Editorial Projects in Education (EPE) Research Center

May 2012

It’s essential that great policies are not just created but also effectively articulated to those who must execute them. Policy implementation means putting theory into practice, wherein many logistic and technical complications can arise. This has happened in the case of teacher evaluation and accountability policies. Addressing these implementation issues is critical to education reform; as a result, the education reform organizations ConnCAN, 50Can, and Public Impact address questions and obstacles that arise in teacher evaluation in their May 2012 report, “Measuring Teacher Effectiveness: A Look ‘Under the Hood’ of Teacher Evaluation in 10 Sites”.

While many school districts have stuck with the same ambiguous methods of teacher evaluations, the report examines ten sites that include states, school districts, a charter school network, and a graduate school program (Delaware; Rhode Island; Tennessee; Hillsborough County, FL; Houston, TX; New Haven, CT; Pittsburgh, PA; Washington, DC; Achievement First; and the Relay Graduate School of Education in New York City). These institutions are all trying more rigorous, comprehensive approach to teacher evaluations; therefore, the report specifically focuses on their evaluation practices.

The authors consider the ways to measure student achievement and the value of nonacademic measures, like student perception and personal growth. For example, applying value-added measures for only math and science creates a problem for evaluating non-math and science teachers. Delaware is making use of multiple measures: state-defined metrics, approved internal school metrics, and growth goal measures. This combination of measures can compensate one assessment’s strength with another’s weakness. Achievement First, a charter network of twenty schools, uses lower weights for test performance in ungraded subjects, but includes student character development and quality instruction input in its evaluations. These are only a few strategies being used, in what the authors suggest are not perfect systems, but ones that show the way forward.

Readers probably won’t find an end-all be-all solution to teacher evaluation in this report. What you will find is a starting place—to brainstorm which methods best fit your objectives. We can learn a lot from these innovators. After all, an abstract idea isn’t much to the world, but when it is put into action it has potential, and that’s a start.

Measuring Teacher Effectiveness: A Look “Under the Hood” of Teacher Evaluation in 10 Sites

By Daniela Doyle and Jiye Grace Han

ConnCAN, 50Can, and Public Impact

March 2012

In this report, the Friedman Foundation for Education Choice looks at new models for schools. Using the term “greenfield,” from Rick Hess’ vision of areas where there are unobstructed, wide-open opportunities to invent and build, greenfield schooling strips down ideas of the traditional schoolhouse and gives schools the freedom to grow by tailoring education to a wider variety of students.

The report challenges the choice system as it currently stands, saying that existing school choice programs, while delivering slightly better outcomes, are not challenging the public school sector as they need to be. Greg Foster, who co-authored the report, begins by stating, “We know from previous research that vouchers (and equivalent programs like tax credits and ESAs) consistently deliver better academic performance, but the size of the impact is not revolutionary.”

Greenfield schools, the report states, would aid in a move to universal choice, a prerequisite for schools to innovate and grow and to prevent the shuffling of children from public to private schools. Universal choice would open opportunities to children of all ethnicities and income levels, many of whom have been excluded from private schools because of cost. Universal choice aims to lower tuition, and allow private schools to expand and serve new populations, which would afford educational entrepreneurs with dramatically more freedom and support than they currently enjoy even in charter schools. According to Foster, in communities where wider choice has been introduced, academic performance has improved.

While Ohio has several voucher programs, Foster believes the state’s families could benefit from universal choice due to the makeup of the private school sector in the state.

The Greenfield School Revolution and School Choice

By Greg Foster and James L. Woodworth

The Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice

June 2012

The Center for Reinventing Public Education (CRPE) takes a look at how strong charter management organizations manage staff to maximize the instructional and cultural coherence of the school.

The report uses data collected from a study of charter management organizations (CMOs) by Mathematica Policy Research and CRPE. The data includes interviews with nearly 150 teachers and leaders in 10 CMOs along with survey information from 37 central offices and more than 220 principals. The authors examined CMOs which had practical control (they could remove principals), were brick-and-mortar schools serving general student populations, and operated at least four or more charters.

Generally, the study found CMOs managed their teacher talent to impact cultural coherence using three levers.

First, they recruited and hired for fit. This can include targeting pipelines such as Teach For America and other teacher programs or schools that match their own school’s work culture and ideals. One hiring strategy is to communicate clearly what the school values most to its prospective candidates; another is to require applicants to submit sample lesson plans or to teach demonstration lessons (to gauge how they interact with students). Some CMOs involved other school community members, such as students and parents, to discern soft skills.

Second, they used intensive and ongoing socialization. Teachers reported they received feedback from both formal and informal observations given by their principal and peers. Not only did they cover instructional methods along with responding to behaviors, but the evaluations were expected to result in improving what is going on in the class room and ultimately helping students be successful. Real time feedback is given as a way to support teachers in executing the schools vision and to hold them accountable.

Third, they align pay and advancement to organizational goals. Teachers who excelled could be offered work in coaching and development as a way of supporting organizational goals and improving teacher practice. Monetary incentives were provided in the schools surveyed for taking on extra duties along with individual and school performance bonuses. Interestingly enough, the leaders’ professional opinion mattered more than assessments or performance metrics, when rewards were used.

The report draws a number of conclusions that can benefit the approach other charter and traditional districts take in using a more integrated approach to recruiting and keeping talent. By creating a cohesive process for recruitment, evaluation, and rewards, these schools have built an environment where teachers clearly know the expectations and what they can do to impact the school’s instructional and cultural coherence. District leaders can learn from the way CMOs manage talent if they are able to give the freedoms and supports along with the process.

Managing Talent for School Coherence

Center on Reinventing Public Education

Michael DeArmond, Betheny Gross, Melissa Bowen, Allison Demerritt, and Robin Lake

May 2012