What’s behind Ohio’s drop in the national Quality Counts ranking?

Education Week just issued its twenty-first “Quality Counts” report card for states.

Education Week just issued its twenty-first “Quality Counts” report card for states.

Education Week just issued its twenty-first “Quality Counts” report card for states. Ohio’s grades are so-so—and nearly identical to last year’s. Yet with a “C” overall and ranking twenty-second nationally, the Buckeye State’s standing relative to other states has fallen dramatically since 2010 when it stood proud at number five.

Ohio’s slide in EdWeek’s Quality Counts ranking has become easy fodder for those wishing to criticize the state’s education policies. Those on the receiving end of blame for Ohio’s fall have included: Governor Kasich (and the lawmakers who upended former Governor Strickland’s “evidence-based” school funding system), Ohio’s charter schools (never mind that nothing whatsoever in the EdWeek score cards takes them into consideration!), and even President Obama (specifically for his 2009 Race to the Top program). I’ve lost track of the number of times I’ve heard or read that Ohio’s plummeting ranking is incontrovertible evidence of things gone awry.

An almost-twenty slot drop in rankings sounds terrible, but my guess is that many people who lament it don’t know what the ratings comprise or that EdWeek’s indicators have changed over time. Let’s take a look at the overall rankings, and then take a deeper dive into changes to Ed Week’s report card to help explain Ohio’s decline.

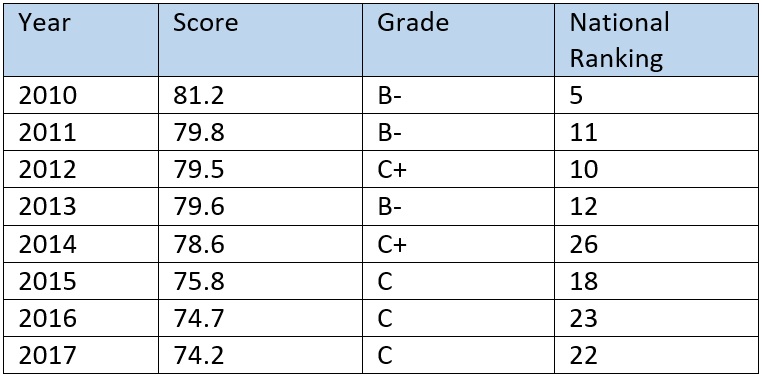

Table 1 shows Ohio’s performance on the Quality Counts assessment from 2010 to 2017. Ohio’s national ranking and points earned have slipped since 2010 (used here as a starting point as it represents the high-water mark for the state on this particular report card), even while its grade continues to hover in the B-minus to C range.

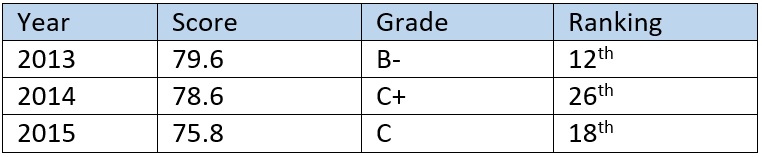

Table 1: Ohio scores on Education Week’s Quality Counts report card

The 2017 report card is based on three sub-categories.

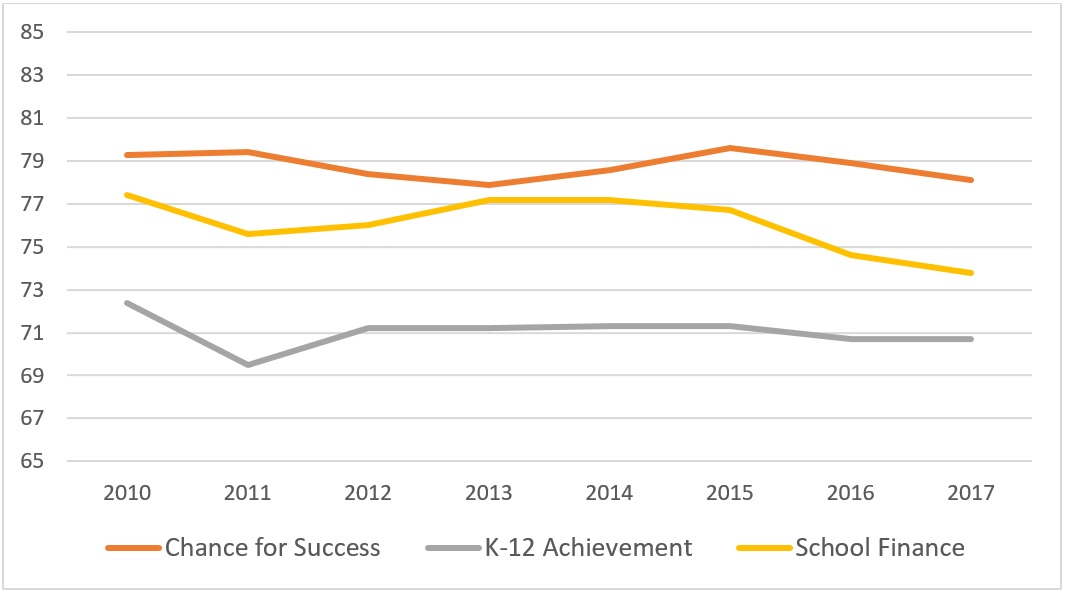

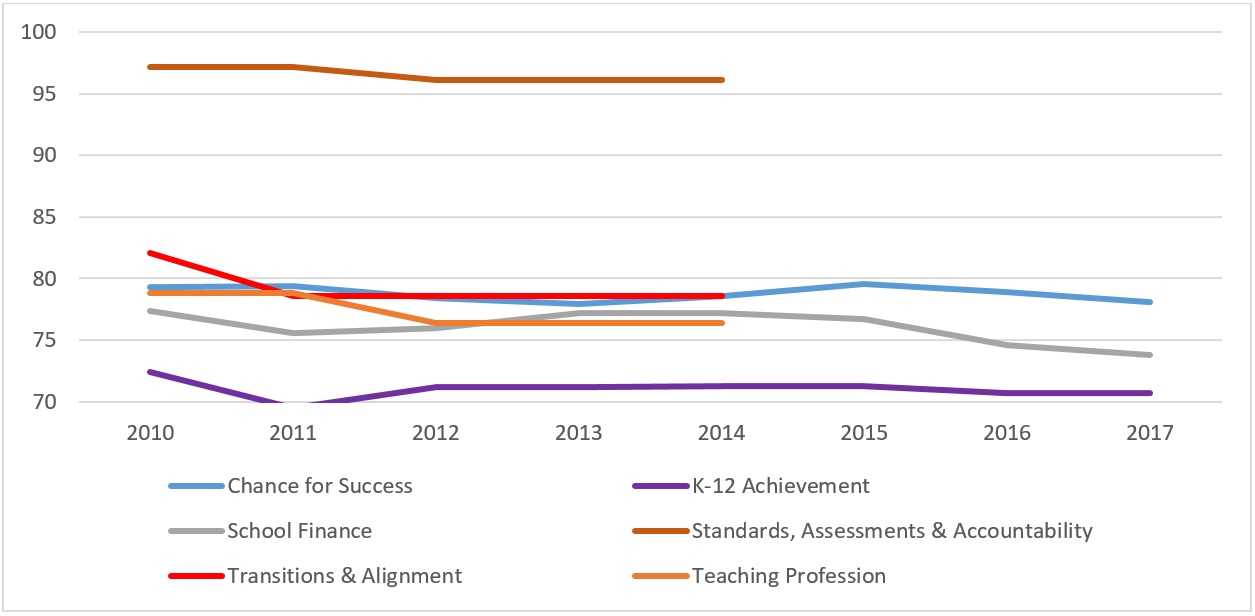

Graph 1: Ohio’s Quality Counts sub-scores, 2010-2017 (three categories)

As Graph 1 depicts, Ohio’s sub-scores are largely flat. Chance for Success dropped by one point in the last eight years; K-12 Achievement fell by less than two points; and School Finance three and a half points. So why has Ohio’s overall rank suffered so greatly?

There are at least two reasons behind Ohio’s fall from fifth that have nothing to do with its actual performance. The first is the change in composition of the report cards and the other has to do with national context.

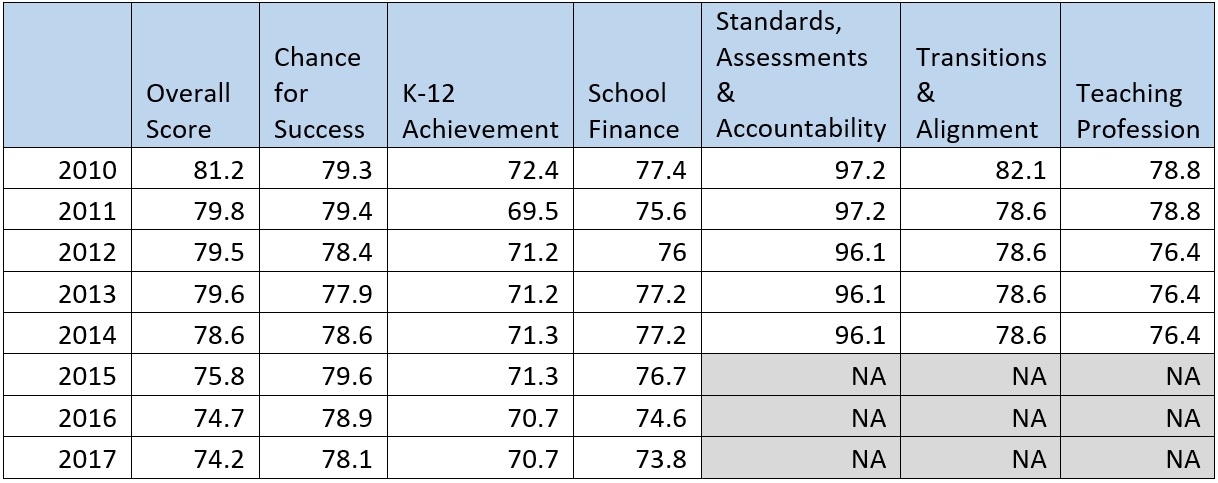

Prior to 2014, Education Week graded states in six categories instead of three. Two of these—“Standards, Assessments, and Accountability” and “Transitions and Alignment”—were among Ohio’s top-rated categories, with Standards the only category in which Ohio ever received an A. Table 2 below makes clear that the shift to just three categories in 2015 essentially knocked out Ohio’s highest-rated components, causing an overall decline in its score. Indeed, the largest single-year drop occurred between 2014 and 2015 when Quality Counts was downsized.

Table 2: Ohio’s sub-scores on Education Week’s Quality Counts report card (0-100)

Graph 2 includes all of Ohio’s sub-scores over time, including the three that were removed from the report card (shown in red and oranges below).

Graph 2: Ohio’s Quality Counts sub-scores, 2010-2017 (six categories)

The change in EdWeek’s report card at least partially explains Ohio’s decline in score as well as rank over the decade. Still, readers might wonder why Ohio dropped so suddenly from twelfth to twenty-sixth in 2014—a year before Standards, Assessments, and Accountability (and the other metrics) were removed. That brings us to the second reason for Ohio’s change in relative rankings, which likely had less to do with what Ohio did or didn’t do, and more to do with what happened in other states. The Buckeye State was an early adopter of Common Core state standards and aligned assessments, voting to adopt them in 2010. And as a Race to the Top winner the same year, it was ahead of the pack in adopting new statewide teacher evaluation systems (a component of the old “Teaching Profession” category). It is unsurprising that Ohio as an early adopter of reform earned high marks on these measures.

Ohio’s fourteen-slot fall between 2013 and 2014 very likely resulted from the changes rapidly occurring in other states that earned them extra points Ohio already had under its belt. Other states adopted and implemented the Common Core, tougher assessments, and teacher evaluation systems—all of which boosted their scores. Ohio’s actual score only dropped by a point the year its ranking plummeted. Conversely, its score fell three times as much the following year (2015) while its ranking rose by eight slots. The lesson here is that relative rankings are just that—relative.

Table 3: Ohio’s dramatic ranking shifts from 2013-2015

Resorting to broad generalizations about Ohio education based solely on the national Quality Counts report card is misinformed at best and intellectually dishonest at worst. Even so, much of the Quality Counts metrics are valuable and can help inform policy priorities. Ohio’s poor showing for NAEP achievement gaps by income; preschool and kindergarten enrollment; funding equity; and adult educational attainment should be especially concerning to us. Ohio leaders wanting the state to compete as a thriving place of opportunity for families should keep close tabs on these metrics, always pushing for ways to move the needle. What they shouldn’t do is pay attention to hyperbolic claims about the demise of our state—at least, not based on this particular report card.

Peter Cunningham recently called district-charter collaboration the “great unfilled promise” of school choice. He explains the possibilities by pointing to a host of cities that are already benefiting from collaboration: In New York City, districts and charters are partnering to improve parent engagement. In Rhode Island, charters are sharing with district schools their wealth of knowledge on how to personalize learning effectively. Boston has district, charter, and Catholic schools working together on issues like transportation and professional development and has successfully lowered costs for each sector. The SKY Partnership in Houston is expanding choice and opportunities for students. The common enrollment system in New Orleans has solved a few long-standing problems for parents (like issues with transparency), and partnerships in Denver have set the stage for even more innovation. Though the type and extent of collaboration differs in each of these places, the bottom line is the same: Kids benefit.

Here in the Buckeye State, there are thousands of kids in need of those benefits. Our most recent analysis of state report card data shows that within Ohio’s large urban districts (commonly known as “the Big Eight”), proficiency rates were far below the state average in fourth- and eighth-grade math and ELA. Each of these districts has a significant population of disadvantaged students similar to those that the district-charter partnerships in other cities are serving well. It stands to reason that district-charter collaborative models would greatly improve both the opportunities for and the outcomes of Ohio students.

But things in the Buckeye State are a bit more complicated. For starters, Ohio charters don’t have access to the same resources that charters in other states do, and that’s led to some serious squabbling about who’s stealing from whom. A 2016 survey of Ohio charter principals found that the biggest barriers to growth included lack of funding, trouble securing facilities, and a lack of district cooperation on issues like transportation and student records. Districts, meanwhile, claim that they’re the ones who are being shortchanged. Working to reform funding and access to facilities could go a long way toward making the sectors more amenable to collaboration.

But even with meaningful reform, the tensions between districts and charters in Ohio could remain. After years of being pitted against one other, trust is in short supply. The truth is that there are few tangible incentives for charters and districts to stop finger-pointing and start working together. But if the goal of both sectors is to do what’s best and right for kids, then collaboration can’t remain a pipe dream. When districts and charters continue to operate in silos, kids pay the price.

Fortunately, Cleveland’s existing district-charter partnership is a positive sign of what could be in the Buckeye State. Plans were initiated back in 2012 with the Cleveland Plan, and by 2014, the Cleveland Metropolitan School District (CMSD) began to engage with local charters in earnest. The city became a "Gates Compact City" in 2014—charters and the district signed a pledge to “improve collaboration and work toward shared goals” and were provided with a planning grant to support their work. Progress has continued since, and the Cleveland Education Compact now boasts subcommittees in which district and charter school leaders work jointly on issues like professional development, special education, policy/advocacy/funding, and enrollment and record sharing. No partnership is perfect, and CMSD and its charter partners will certainly have their ups and downs as they determine how best to collaborate moving forward. But the willingness from both groups to work together is worth acknowledging, and their collaborative model is worth considering in other Ohio cities.

Many folks in Ohio didn’t think charter reform could ever become a reality, but in 2015, the Ohio General Assembly passed House Bill 2, a comprehensive reform bill with provisions designed to incentivize higher performing authorizers, charter school boards, and management companies. Despite the short time frame, we’ve already started to notice the charter sector changing for the better. With these comprehensive reforms under our belt and $71 million in CSP funds waiting in the wings, 2017 could be a good year for Ohio charter schools. A good year would certainly be welcome. But a great year would be even better—and a great year becomes far more possible if Ohio can solve the problem of limited collaboration between districts and charter schools.

More than sixty years after Brown v. Board, traditional district schools are more often than not still havens of homogeneity. Static land use guidelines, assignment zones, feeder patterns, and transportation monopolies reinforce boundaries that functionally segregate schools and give rise to the adage that ZIP code means destiny for K-12 students. Asserting that student diversity is an object of increasing parental demand, at least among a certain subset of parents of school-age kids, the National Charter School Resource Center has issued a toolkit for charter school leaders looking to leverage their schools’ unique attributes and flexibilities to build diverse student communities not found in nearby district schools. The report cites a number of studies showing academic benefits of desegregated schools, especially for low-income and minority students. It is unlikely that the mere existence of documentable diversity is at the root of those benefits. More likely, it is a complicated alchemy of choice, quality, culture, and expectations that drives any observable academic boosts. Garden-variety school quality is a strong selling point for any type of school, but this toolkit sets aside that discussion to focus on deliberately building a multi-cultural student body for its own sake. Bear that in mind as we go forward.

Building diversity is not easy, even in a flexibly run and technically borderless charter school. The toolkit provides “context about research and the legal and regulatory guidance” in four main areas required to be addressed: defining, measuring, and sharing school diversity goals; planning school features to attract diverse families; designing recruitment and enrollment processes; and creating and maintaining a supportive school culture.

Goal-setting and recruitment are thorny from the start, the report warns, as using racial or cultural characteristics to even set an enrollment target is riddled with concerns around quotas and discrimination. In states where charter location is less regulated, the calculus may be how to attract families of color to a school in a predominantly white neighborhood. In states like Ohio, where charter location is limited to low-performing school districts, the calculus may be reversed. Either way, the toolkit provides valuable guidance for negotiating these potential pitfalls. Also addressed – although not solved by any means – are the severe constraints charters in many states face in terms of facilities and transportation. The mechanics and legalities of diversification can easily overwhelm the best of plans before the desired diverse student body even gets in the door.

My colleagues here at Fordham have written extensively about the challenges of teaching kids who are at vastly different levels of achievement, which is more likely in a diverse school. The new toolkit has a section on school staffing, training, and professional development, but the resources highlighted there are more about cultural awareness and discipline practices than actually teaching the students being recruited. I highly recommend Mike Petrilli’s 2012 book The Diverse Schools Dilemma for more on the latter.

The tips and guidance in this toolkit are helpful and may give charter school leaders insight into areas where well-intentioned plans to build a diverse student body could unexpectedly founder. But with no discussion of academic quality as a key means of attracting students, we are left with a roadmap to somewhere we might want to go. But not until after we’ve visited the bigger and better-known stops along the way.

SOURCE: “Intentionally Diverse Charter Schools: A Toolkit for Charter School Leaders,” National Charter School Resource Center (January, 2017)

NOTE: The State Board of Education of Ohio on December 13, 2016 debated whether to change graduation requirements for the Class of 2018 and beyond. Below are the written remarks of John Morris, given before the board.

Members of the Board,

Thank you for giving me a moment to offer testimony on behalf of the construction industry. Members of the industry sent me here to thank you for setting a new higher bar with the class of 2018 graduation requirements. We are excited that this board has supported maintaining high standards for graduating and earning a diploma in the State of Ohio. Members of the construction industry were very pleased when the phase out of the Ohio Graduation Test was announced in favor of multiple end-of-course exams and the opportunity for an industry credential to help a student graduate. We expect this new system to be an improvement over the current system that graduates many without the skills to succeed in college and continuously FAILS to introduce others to the hundreds of thousands of pathways to employment via industry credentials.

For many decades, industries such as construction and manufacturing enjoyed a steady stream of individuals coming directly from "vocational" schools with earned industry credentials and experience. The construction industry regularly took graduates and gave them advanced placement into level three of apprenticeship, only two years from full journeyman status. That luxury and system of education is now all but dead and gone. The increased emphasis on a pre-college curriculum for all has severely diminished the ability of high school students to learn a skilled trade while in school and the elimination of middle school "shop" classes has reduced the number of students who learn at young age of their God-given talents in the trades. You see when I was in sixth grade, I learned in middle school shop class that I was not going to be a carpenter when I struggled to build the birdhouse. I knew I would not be a welder or plumber when I could not properly seal two metal objects together; but I was one who could wire a lamp and do the math needed to calculate wattage. When I struggled in high school, I chose to become an electrician. I owned my own company by the age of 28. I paid my way through college debt-free thanks to a trade. I now hold multiple masters degrees and taught economics at the University of Cincinnati. An industry credential and skilled trade open the door to opportunity for me and it can for many others.

The current graduation requirements that offer alternative pathways through industry credentials are perfectly designed to fix a broken system that mistakenly tells every child who gets a diploma that they are college-ready. We all know this is not the case; yet we've heard that many are already talking about making the tests easier and/or reducing the number of points required to earn a diploma rather than increasing the emphasis on schools to work with industries like construction to help steer students into choices that don't involve certain college failure and accumulation of unforgiveable debt. We applaud this board and the Ohio Department of Education for creating a system that includes pathways to graduation via industry credentials and sincerely hope that you hold onto the idea of higher standards for graduation. We all know that not everyone should go to college and industry credentials offer an alternative pathway to success in life—one without failure and debt. The only way school districts will pursue these pathways is to maintain the system as it is. Do not make their jobs easy. Keep the standards as they are written and make the superintendents do what they should be doing anyway—working to find a path to success for all students, not just those who are on a college path. Construction professionals stand ready to help school districts build pathways to credentials in our industry and are pleased to offer Ohio Students a debt-free pass to a lifetime of earnings through a skilled trade.

Mr. Morris is president of the Ohio Valley Construction Education Foundation, based in Springboro, Ohio.

NOTE: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

Last fall I retired to Northeast Ohio, where my wife and I have family, from Washington state, where I’d been staff to the State Board of Education and the state legislature. In perusing the Plain Dealer one morning, I felt that I could as well have been back in Olympia.

The story described new state high school graduation requirements linked to higher standards defining readiness for college and career that had been set by Ohio’s State Board of Education and the fierce backlash ensuing from superintendents and others. The State Department of Education calculated that nearly 30 percent of high school juniors were likely to fall short of graduating next year if the new requirements were applied to them. Superintendents organized a protest rally—dubbed by one State Board member a “march for mediocrity”—on the statehouse steps. In light of the concerns voiced, the Board created a task force to make a recommendation on whether the requirements should be changed or phased in in some manner.

That the present controversy resonates with my experience in Washington is not such a surprise. I could have moved to Ohio from many other states grappling with the same question: Can you have higher standards for granting a high school diploma geared to measures of career and college readiness without adversely affecting graduation rates, at least for a while? How do we best resolve the inherent tension between the twin goals of higher standards and higher graduation rates?

While the parallels between Washington and Ohio are striking, there are significant differences, too. I relate the Washington story not for its intrinsic interest, but in the hope that there may be things to be learned from the Evergreen State experience.

While Ohio requires students to earn a cumulative passing score on a series of end-of-course tests to graduate, Washington has set passing scores on statewide assessments developed by the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC) linked to Common Core State Standards as a bar for earning a state-approved diploma. Legislation enacted in 2013 required the State Board to establish the scores students must reach to obtain a state diploma. “The scores established by the state board of education for the purpose of earning a certificate of academic achievement and graduation from high school may be different from the scores used for the purpose of determining a student’s career and college readiness,” the act said.

In rule, the Board adopted aspirational language declaring that, “The state’s graduation requirements should ultimately be aligned to the performance levels associated with career and college readiness.” But there is no law requiring that the two be so aligned, and pressure from “the field” will continue to be strong that they not be aligned lest graduation rates slip.

In a November 2014 presentation on alternative assessments, a consultant to the Board posed the big, unpleasant but unavoidable question, “How can we increase the rigor of a high school diploma and the number of students graduating at the same time?” It is the same question confronting the Ohio State Board now.

In January 2015, the Washington Board formally stated an intent to adopt an “equal impact” approach to setting the minimum, “or cut,” scores for graduation. Under this approach, the cut scores for the Smarter Balanced assessments would result in the same projected percentage of students earning a diploma as would have been the case had the state still been using the old, superseded state assessments aligned with earlier, less rigorous state standards.

In August, the Board adopted scores implementing that policy. Superintendents supported the action as fair to students while their districts continued to transition to the new standards and assessments. Business-backed education reformers criticized it as a retreat from standards. “The Washington State Board of Education today fell short of setting a clear path for our state toward all students graduating high school prepared for their next step in life,” said the Seattle-based League of Education Voters.

A former school board member and community college instructor asked, “Isn’t it time that we became serious about education? Setting cut scores based on how many this will allow to pass just further depreciates a high school diploma. We know by community college remediation rates that the current high school diploma is not acceptable. Why continue this myth?”

The Board stated that the initial score-setting begins the process of moving toward more rigorous college-and career-ready standards, and “was not done to compromise or confuse our goal.” Its good intent is not to be doubted. To reiterate, however, there is no law requiring that scores established for graduation move toward and ultimately equal those for career and college readiness, and none on the horizon. I will watch from my new home to see whether the Board’s intent is realized in a political environment not friendly to it.

As I keep an eye on events in Washington, having been so involved for so long, I’ll also be following the deliberations of the task force created by the Ohio State Board of Education with great interest.

I find much to credit in Ohio’s graduation requirements. Having students achieve a minimum cumulative number of points on state end-of-course tests rather than meet a standard on each consortium-designed test and the alternative pathways to graduation offered, including an industry credential and established workforce readiness assessment, are worthy of examination, and perhaps emulation, by other states.

Change is hard, we all know. It is prudent for the Board to step back and, with the help of the task force, consider what may be the best way to implement the new requirements while doing the least harm. At the same time, the Board should resist the inevitable pressure to back away from higher standards. It is critical that board members not lose their focus on what will best prepare students—meaning this generation of students and not some future one—for success in life after high school in a very different and more challenging world from when my generation was in school. The stakes are very high.

Jack Archer served as director of basic education oversight at the Washington State Board of Education until his retirement in 2016. He lives in Fairview Park.

Much prior research indicates that youngsters from single-parent families face a greater risk of poor schooling outcomes compared to their peers from two-parent households. A recent study from the Institute for Family Studies at the University of Virginia adds to this evidence using data from Ohio.

Authors Nicholas Zill and W. Bradford Wilcox examine parent survey data from the National Survey of Children’s Health. This dataset contains information on 1,340 Ohio youngsters—a small but representative sample. The outcomes Zill and Wilcox examine are threefold: 1) whether the parent had been contacted at least once by their child’s school for behavioral or academic problems; 2) whether the child has had to repeat a grade; and 3) a parent’s perception of their child’s engagement in schoolwork.

The upshot: Buckeye children from married, two-parent households fare better on schooling outcomes, even after controlling for race/ethnicity, parental education, and income. Compared to youngsters from non-intact families, children with married parents were about half as likely to have been contacted by their school or to have repeated a grade. They were also more likely to be engaged in their schoolwork, though that result was not statistically significant.

An estimated 895,000 children in Ohio live in a single-parent household, according to the Annie E. Casey Foundation. Each of them may feel the same love and affection as their peers from married families, but the stark reality, as indicated by study after study, is that on average, they face disadvantages manifested in lower schooling outcomes. The challenge for schools is to help all of their students—including ones from single-parent families—to beat the odds.

Source: Nicholas Zill and W. Bradford Wilcox, Strong Families, Successful Students (Institute for Family Studies).