About a month ago, I published an analysis of the starting salaries of teachers working in school districts across the Cleveland and Columbus metro areas. Strong entry-level pay is crucial as schools work to attract talented folks into the profession. We saw that these salaries, while not exceedingly lucrative, are solid, clocking in at roughly $45,000 to $50,000 per year, not including benefits. High-poverty districts such as Cleveland and Columbus pay above-average salaries, though I also discussed ways that they and other districts could further prioritize entry-level salary to attract teachers to their schools.

First-year pay is only the beginning, of course. Wage growth over time also matters to teachers, and impacts schools’ ability to retain effective instructors. When schools increase pay too little, they are more likely to see their educators head for the exits. More generous pay raises, on the other hand, increase the likelihood that teachers stay put.

Strong wage growth early in teachers’ careers is especially important, as attrition tends to be highest in those years. As Chad Aldeman has shown, roughly a third of U.S. teachers leave the profession by the end of their fifth year of teaching, and just over half exit by their tenth. A recent study from the RAND Corporation indicates that urban, high-poverty schools suffer more teacher attrition than in other locales. This amount of turnover contributes to educator shortages, creates more “churn” in schools’ staff, and represents a loss of talent developed during the beginning stages of teachers’ careers. While various factors explain why so many teachers exit early, some is surely related to dissatisfaction about pay.

But just what are the salaries of Ohio’s early-career teachers? Are they strong enough to keep teachers from leaving? This piece looks at the fifth- and tenth-year teacher salaries of districts in the Columbus metro area during the 2023–24 school year (though not discussed below, salary data for Cleveland area districts are available at this link). The focus is on teachers whose highest degree is a bachelor’s.

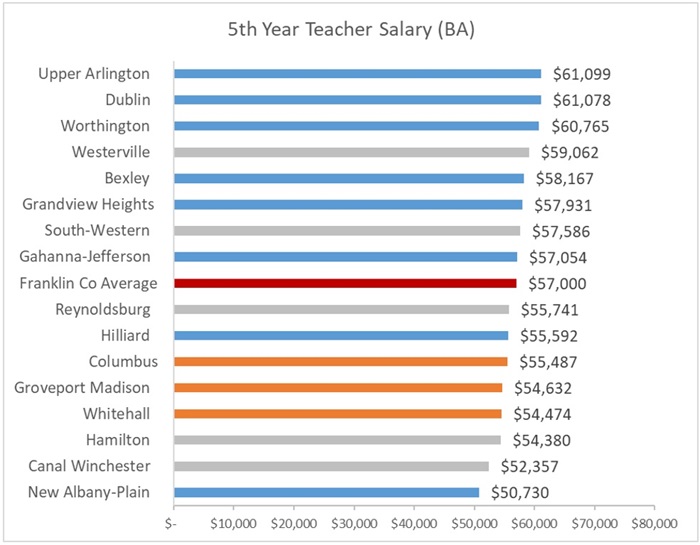

Figure 1 shows that the average fifth-year teacher salary in Franklin County was $57,000, which is about $10,000 higher than the average starting salary for these districts. Salaries vary, with Upper Arlington paying the highest wages, while New Albany-Plain pays the lowest at just over $50,000. Columbus City Schools pays its fifth-year teachers $55,487, just under the county average and a disappointingly small pay bump versus its first-year salary of $49,321.

Figure 1: Franklin County school district salaries for fifth-year teachers, FY 24

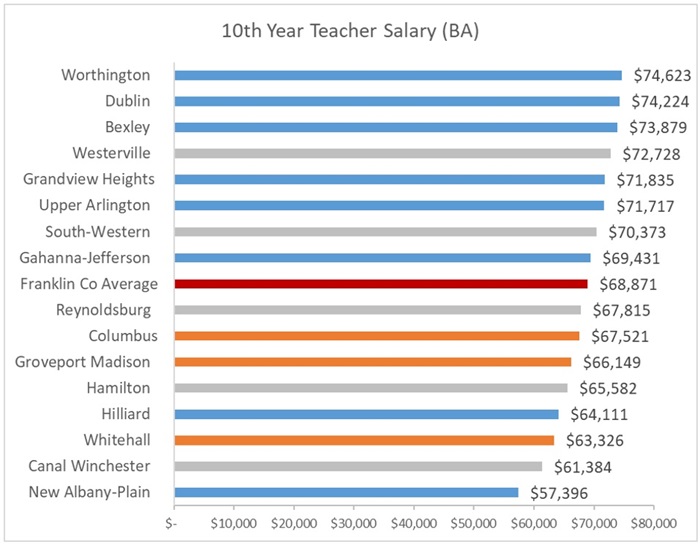

Figure 2 shows that the average tenth-year salary is nearly $69,000 per year, about $12,000 higher than the average fifth-year salary in Franklin County. This amount is right around the average teacher salary for all Ohio teachers. We again see some variation in tenth-year salaries with Worthington and Dublin paying nearly $75,000 and New Albany-Plain paying the lowest at just over $57,000. Columbus again falls just beneath the county average at $67,521.

Figure 2: Franklin County school district salaries for tenth-year teachers, FY 24

Whether early-career teacher salaries between roughly $55,000 and $75,000 per year are good enough is certainly debatable. Some might see them as reasonably generous; after all, these wages are right around the median salary for an Ohio worker. Others will disagree. In fact, a recent op-ed in the Washington Post argued that every teacher in America—no matter their experience or effectiveness—should be paid at least $100,000 per year. That proposal would be incredibly expensive, at least at current student-teacher ratios, but calls to significantly raise teacher pay across the board have long been made by the unions and policymakers.

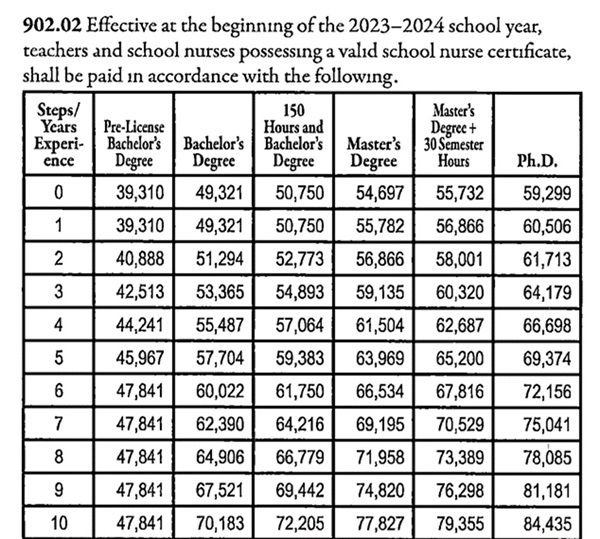

Most calls to boost teachers’ salaries, however, ignore a more basic structural problem with teacher pay, one that likely contributes to the high rates of turnover early in teachers’ careers and in high-poverty districts. That’s the longstanding practice—enshrined in Ohio law—of paying teachers according to “step and lane” salary schedules. This method starts first-year teachers at the bottom of the pay scale and provides incremental salary increases as they gain experience and/or earn a master’s degree. Figure 3 illustrates, using Columbus City Schools’ schedule.

Figure 3: Example of a teacher salary schedule

While there is a certain efficiency to this type of step-and-lane pay system, it also treats teachers like widgets rather than skilled professionals. That creates three specific problems, particularly in regard to early-career teachers.[1]

First, it makes it harder for schools to retain teachers. Districts can’t simply deviate from this schedule, even if they want to pay a particular teacher more in an effort to retain her. For example, an outstanding third-year math teacher might get an offer from another employer worth more than she is currently paid. District administrators cannot match that salary to keep her in the classroom. Why? Because they have to pay according to the salary schedule. Unfortunately, an early-career salary may not be enough to keep her on board.

Second, a rigid pay system fails to reward teachers who go the extra mile on behalf of students. If teachers know their salaries will increase at roughly $2,000 increments each year—no matter what—they have little incentive to go above and beyond. Highly effective teachers shouldn’t have to wait two decades to reach the higher salary echelons, but that’s what our current system does.

Third, this type compensation system doesn’t encourage teachers to remain in the toughest schools, most notably those located in high-poverty communities. Columbus City Schools, for example, likely loses a significant number of early-career teachers to other districts because it only offers modest pay raises each year. They bolt for jobs in the suburbs where the pay is higher and working conditions easier.

What to do? Within the conventional step-and-lane framework, districts could more heavily “frontload” teacher pay so that early-career teacher salaries escalate at a faster pace. For example, Columbus, a district where early-career salaries grow relatively slowly, might consider a schedule that provides faster pay raises early in teachers’ careers (or better yet, more specifically for high-performing, early-career teachers). This would help discourage its junior teachers from eyeing jobs in nearby districts, or seeking employment in other career fields.

A better solution is to give districts greater flexibility around pay, so they can compensate teachers in ways they believe best retain and reward employees. If a district wants to stick with the step-and-lane schedule, so be it. But bolder district leaders should also be allowed to experiment with alternative pay strategies, including ones that provide their early-career teachers with stronger financial incentives to remain in the classroom. This approach would require Ohio lawmakers to remove provisions that currently require districts to implement a salary schedule based on years of experience and degrees-earned.

For too long, schools have not provided the type of financial incentives needed to keep many of their talented young professionals in their classrooms. With some help from lawmakers, districts, including high-poverty urban districts, could be empowered to move to systems that pay teachers more strategically, and better ensure that every student in Ohio has an exceptional teacher leading their classroom.

[1] The following comments apply to veteran teachers, too, but they are also higher on the pay schedules and thus less susceptible to leaving for a higher-paying job. They also have incentives to stay in the classroom based on the way pension benefits accrue (they sacrifice significant retirement wealth for leaving teaching).