Ohio, like many other states, has made college and career readiness a major priority. The state’s strategic plan for education, for instance, aims to increase the number of young people who enroll in college or technical schools, participate in apprenticeships, enlist in the military, or obtain gainful employment. Achieving this goal will require strong policies and practices, along with the ability to track these post-secondary outcomes to gauge progress and pinpoint areas needing attention.

On the higher education side, Ohio already reports reliable data on college going and degree completion. The state does this through linkages to the National Student Clearinghouse, a nonprofit organization that collects data from almost all U.S. colleges and universities. These results appear on district and school report cards. From this same data source, we can also see statewide trends in college enrollment and completion, the latter of which are on the rise.

But not everyone pursues post-secondary education, at least right away. The most recent data indicate that 44 percent of the class of 2016 did not enroll in college shortly after high school. So what happens to those young people? Are they on pathways to rewarding careers?

Information about these workforce questions is far murkier. The state’s Career-Technical Planning District (CTPD) report card contains statistics about career-and-technical education (CTE) students’ outcomes in the areas of apprenticeships, military enlistment, employment, and higher education. Sounds promising, right? But there are four problems with Ohio’s current approach to reporting workforce outcomes.

Problem 1: Data are limited to small segment of graduates

The CTPD report card reflects only the outcomes of CTE students, or more specifically “concentrators,” who take at least two career-technical courses in a career field. Across Ohio’s ninety-one CTPDs, 29,675 students were reported as concentrators in 2018–19, thus representing roughly 20 percent of Ohio’s graduating class. Since the state includes no data about military enlistment, employment, or apprenticeships on traditional district or charter school report cards, we have no information about the workforce outcomes of the large majority of Ohio students.

Problem 2: Relies on surveys, with no verification checks

The CTPD data are collected via surveys of graduated CTE students, and no checks are conducted to verify that the results are reported accurately. ODE describes the process this way, with a caution about reliability in bold (my emphasis):

Districts begin following up their students in the fall after they leave.... In the survey, they ask students to tell report [sic] what they did professionally after leaving school, including asking if they are in an apprenticeship, enrolled in post-secondary education, employed or if they joined the military. It is important to understand that for this element, all data are self-reported by the former students. There is no confirmation check performed by ODE or by the districts.

The warning is worth heeding, as there are reasons to doubt the accuracy of these survey data. Some respondents might feel compelled to say they are in the workforce or college, when they really aren’t—a type of social desirability bias. Some of the terms could also be ambiguous: What exactly counts as an “apprenticeship” or “joining the military” (an intention to join, or actual enlistment)? When in doubt, respondents might affirm that they’re doing these things, something of an acquiescence bias.

Due perhaps to these issues, some questionable results emerge. For instance, an average of 4.2 percent of CTE students say they joined the military. While it’s possible that career-technical students are more inclined to enlist, this rate far exceeds the roughly 1 percent of American eighteen- to nineteen-year-olds that the federal government reports as enlisted. Moreover, a few CTPD’s post-secondary college enrollment data look suspect, as their rates significantly exceed those of the traditional school district serving students in the same area.

Problem 3: The employment data are coarse

All that is reported on the CTPD report card is whether a CTE student is employed, or not. It’s a straight up employment rate, with no other information given about the type of employment, career field, or salaries and wages. For example, the Lorain CTPD report card states that 58 percent of students reported employment. Although that statistic is a starting point, it tells us nothing about the quality of the jobs students obtain. What proportion are working full-time compared to part-time? How many are in minimum wage jobs versus entry or mid-level jobs in good-paying career fields? Unfortunately, Ohio doesn’t present anything finer that would help us better understand students’ transitions into the labor market.

Problem 4: Duplication across categories

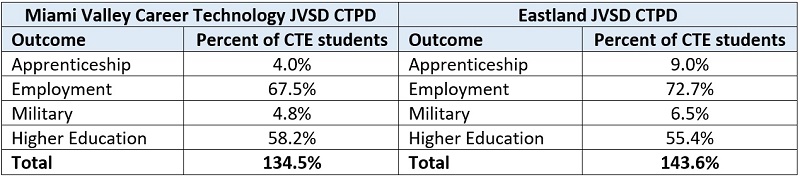

Ohio’s approach to presenting workforce outcomes on the CTPD report cards results in a significant duplication of students. Consider Table 1 below, which displays results for two of Ohio’s larger CTPDs, selected for illustration purposes. It’s clear from the “total” rows that students fall into multiple outcomes, as the percentages exceed 100 percent. This is likely the result of young people who work and attend college concurrently reporting participation in both (those in an apprenticeship or the military may also consider themselves employed).

Table 1: Post-secondary outcomes for two selected CTPDs, 2018–19

Source: Ohio Department of Education. Note: The Miami Valley CTPD oversees CTE in twenty-seven districts in Southwest Ohio; the number of CTE students in its graduating cohort was 953 in 2018–19. The Eastland CTPD oversees CTE in sixteen districts in Central Ohio; the number of CTE students in its graduating cohort was 897 in 2018–19.

Duplicate reporting is not always a bad idea, but in this case, it clouds our picture of students who do not enter post-secondary education. Because we don’t know what fraction of the employment rate represents students who work while in college, we cannot determine the employment rate of non-college-goers.

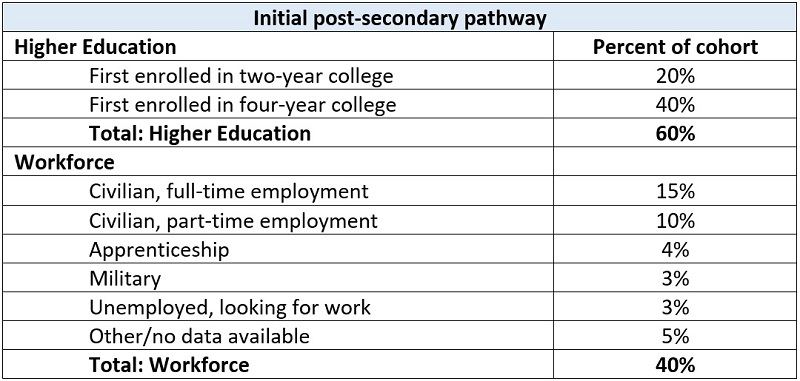

A clearer presentation might split the higher education and workforce data. Table 2 presents a rough sketch of what the reporting could look like. The top panel covers students who enroll full-time in college, while the bottom focuses on those who enter the workforce after high school. Because college students are excluded from the labor market data, this approach offers a sharper picture of the workforce pathways of non-college-goers. This framework could also serve as a basis for presenting more detailed information. For example, the civilian, full-time employment category could be divided by salary (e.g., $30,000 and below, $30,000 to $60,000, etc.) to offer a view of job quality.

Table 2: Proposed framework for reporting higher education and workforce outcomes separately

* * *

In sum, Ohio needs to make advancements in its data collection and reporting methods when it comes to workforce outcomes. Fortunately, the state is currently working to link information systems that should yield more trustworthy data about what students do after high school. That effort received a boost when the Ohio Department of Education recently announced a $3.25 million federal grant aimed in part at connecting K–12 and workforce data. Assembling reliable data, however, is only half the battle. Ohio also needs to consider clear, transparent ways of presenting the information for students attending all schools, whether career-technical or general education.

Ensuring that each student succeeds in college and career remains a central aim of Ohio. Curing our blind spots about workforce outcomes would go a long way in gauging progress toward that admirable goal.