In Ohio, debate over high school graduation requirements has raged for over a year. At various points, policymakers have requested to know more about the graduation policies in other states. It’s worth noting, then, that the Kentucky Department of Education (KDE) recently announced a proposal to change minimum graduation requirements for students entering high school in the fall of 2019—and their proposal shares some similarities with Ohio’s hotly debated rules.

Our southern neighbor’s current high school graduation requirements are pretty traditional: Students must complete at least twenty-two credit hours, with a certain number of credit hours required in specific subject areas. Although there is testing—students are required to take the ACT and a writing assessment, and last year was the first year that newly designed and teacher-developed end-of-course assessments were field-tested for algebra II, biology, and English II courses[1]—results are only used for the state’s accountability system or, in the case of field-testing, for data-gathering purposes. The vast majority of Kentucky students take their classes, amass their credits, and earn their diplomas.

Under KDE’s recently proposed system, that would change. According to a video from Interim Commissioner Wayne Lewis, students would be required to pass new tenth grade reading and math assessments to graduate. Students would also be required to pass a civics test based on the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services test (they are not the first state to do so) and take state science and social studies assessments in eleventh grade. The new proposal maintains the twenty-two credit minimum threshold, but allows students more freedom to personalize their classes in certain subjects to align with their career interests.

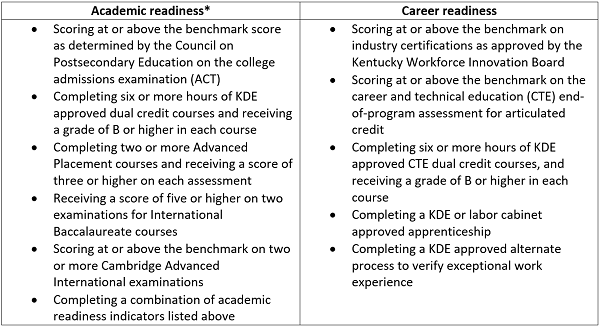

Another significant addition is a requirement for students to demonstrate academic or career transition readiness in order to graduate. Transition readiness is already part of Kentucky’s accountability system, and current state regulations outline how students can demonstrate the two types:

* Demonstration of academic readiness must include one quantitative reasoning or natural sciences learning outcome and one written or oral communication, arts and humanities, or social and behavioral sciences learning outcome.

Overall, Kentucky’s changes represent a significant rise in expectations for students. In his video, Interim Commissioner Lewis explains that the changes are necessary to bring the state’s standards for students into alignment with what businesses and higher education institutions have identified as the “profile” of a graduate. “Currently, our minimum requirements for high school graduation fall short of assuring that our graduates have reached even a basic level of competency in reading and mathematics,” he said. “Neither do our requirements ensure that our graduates are ready for college or the workforce. We can do so much better.”

This reasoning should sound familiar to Ohioans. The graduation pathways that have been the subject of so much controversy were also designed to address the mismatch in the knowledge and skills needed to graduate high school and those demanded by colleges and employers. There are also quite a few similarities between Kentucky’s proposed system and Ohio’s current one, including the use of college entrance exams, state assessments that measure basic academic competency, and industry credentials. Because of these similarities and each state’s unique context, there isn’t much within Kentucky’s new proposal that Ohio policymakers should consider adopting. But there are still valuable lessons to be learned from our neighbor to the south.

First, Ohio must realize that other states are recognizing the importance of high expectations. Although there are still places where diplomas don’t mean much, Kentucky is an example of a state where policymakers are making a serious effort to raise the bar by requiring students to demonstrate academic competency and readiness before they’re awarded a diploma. If Ohio backs down from its current pathways—or continues to enshrine workarounds into law—the consequences would be steep. Not only would businesses struggle to find well-prepared employees, Ohio graduates would struggle to compete with graduates from other states.

Second, we must realize that other states have also recognized the importance of college and career readiness. With a new Perkins law on the books and the rising popularity of CTE across the nation, Ohio must ensure that its CTE sector continues to grow and improve and that career readiness measures remain part of our graduation pathways.

When the General Assembly reconvenes this fall, lawmakers should resist calls to weaken graduation requirements again. Low standards might lead to more diplomas and a higher graduation rate, but they won’t help Ohio—or students and their families—in the long run.

[1] U.S. History end-of-course exams will be created once the state adopts social studies standards.