We heard a lot about the role school choice can play in education reform this week at Jeb Bush’s National Summit (Bush himself called choice the “catalytic converter” of reform). But while the 900 people in attendance rhapsodized about transforming models of education delivery, there was little talk about how one state is trying to enhance choice by unbundling public education.

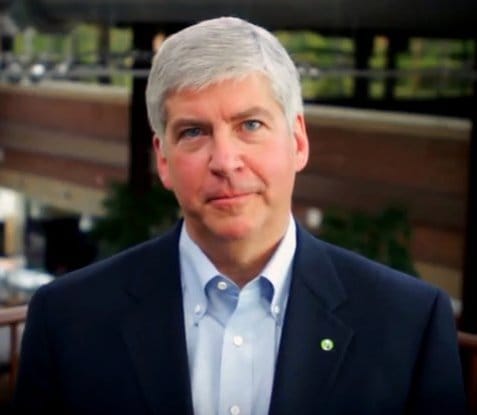

Gov. Rick Snyder unveiled a draft bill that would institutionalize choice and blended learning. Photo from Wikimedia Commons. |

To be sure, up until just this month, Michigan governor Rick Snyder has mostly sloganeered about school models that could impact students “any time, any place, any way, any pace.” But two weeks ago, Snyder unveiled a 302-page draft bill that would institutionalize choice and blended learning in ways that chip away at the artificial boundaries that have historically defined public education in Michigan and beyond.

But for some reason, Snyder can’t generate the national buzz that has inspired education reformers the way Mitch Daniels has done in neighboring Indiana or the way Bobby Jindal has done in Louisiana. That’s perplexing, because what Snyder is proposing is perhaps more transformative than what any of his peers have so far established in statute.

- A high school education in Michigan would be disaggregated to a level where an individual student could shop for courses in her own district, in neighboring districts, at online academies, at community colleges or at state universities.

- No district would ever own a student, but full funding would follow the student to her destination of choice

- Any student could access all public school online-learning opportunities, even those offered in districts that are outside the student’s home district, and the state would cover the cost.

- Funding would be based on performance, partially at first, but proportionately more over time.

- The school year would remain at 180 days, but would be spread over twelve months, not nine.

- Post-secondary scholarships would go to students who graduate from high school early.

There are still many issues for the governor and the state’s lawmakers to work out: Who should be held accountable for students’ performance, and how will courses and student achievement be evaluated? How much will each school be paid for courses or services provided? And, perhaps most importantly, how much can the governor achieve in the state’s singular educational wasteland (Detroit) if he’s going to allow districts to opt out of any open-enrollment plan he proposes (most every Michigan school district participates in the state’s current cross-district enrollment plan except those in suburban Detroit).

Nonetheless, Snyder has developed a proposal that he approached methodically (the governor charged the nonprofit Oxford Foundation–Michigan with the task of designing the plan, and the foundation did so over several months in several public meetings). And he looks to be ready for a bruising fight in the public square, even without the enthusiasm of the broader reform movement.

Snyder has accomplished much in education reform since he was elected in 2010, but most of that impact was felt gradually (like removing the cap on the number of university-authorized charter schools in the state). If he wants to accomplish more in a strongly unionized state, he’ll need to tap the support of the national change-agents and organizations that are ostensibly committed to reform.